“Immigrants From Where?”

The one question no one is seemingly willing to answer

Christmas was supposed to be fun. Unfortunately, reality had other plans in store. Techbros and legal immigration advocates won’t stop talking about the wonderfulness of “high-skilled immigrants”. The problem with this argument, aside from censoring those who disagree, is that immigrants are not a homogenous group, there’s no country called “Immigrasia” where all the immigrants come from. We’re talking about people from literally all around the world and lumping them all together under this one broad term is incredibly misleading. There are tons of people ranging from random anons to political commentators to actual politicians who’ve committed this silly mistake over the last couple of days, but I want to focus on one example in particular because I think it’s the one that will get the point across most effectively. Specifically, this tweet from Alec Stapp where he puts on display the supposed brilliance and innovativeness of immigrants:

Well shit, if he is correct, then I guess this whole immigration debate really is one-sided. How can you possibly be against that, right? Except, again, immigrants are not all the same. When you see statistics like these that praise the achievements of migrants, the question that should come to mind almost intuitively is “immigrants from where?” Unfortunately, Alec doesn’t provide us an answer, but that’s okay, I’m willing to pick up his slack for him.

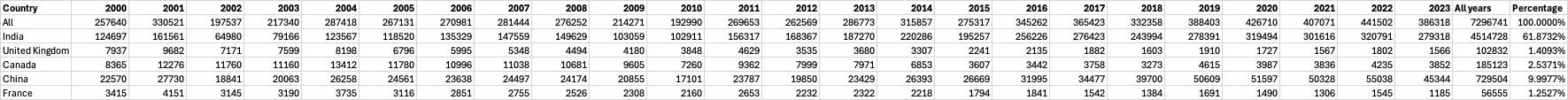

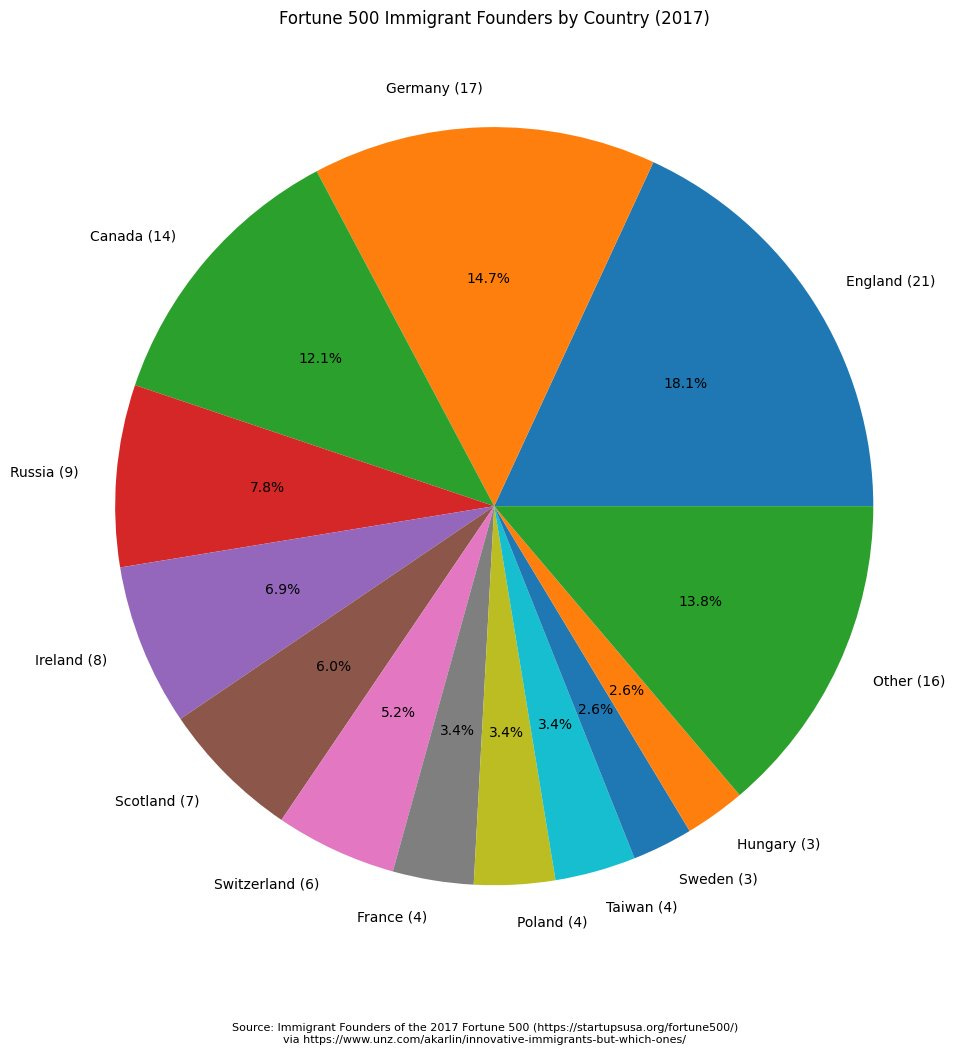

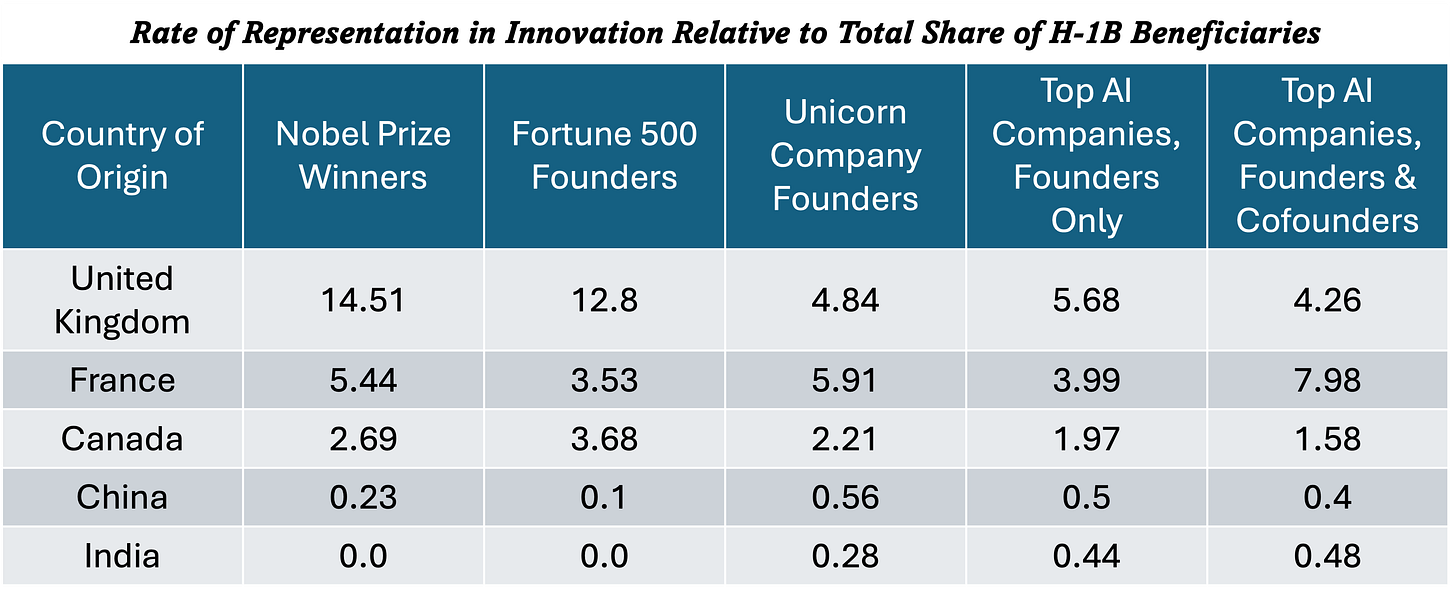

Since much of this debate has been concerned surrounding Elon’s seeming support for expanding H-1B visas, I gathered data from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. Let’s take Alec’s first image, that 65% of Top AI companies have immigrant founders. Well, fortunately for us, the National Foundation for American Policy gives us the place of origin of these founders and cofounders (Anderson, 2023, Tables 1 & 4). I got the share of H-1B beneficiaries for each year for India, the United Kingdom, Canada, China, and France from 2000-2023. The reason why the rest of the countries were excluded is because there were missing entries in some of the years for them. This is fine though because what expanding H-1Bs really means is just importing more Indians, and they are the primary subject of interest here anyways.

Great, now we can use this and compare it with their immigrant share of top AI companies. Here’s the results for founders and cofounders:

And here’s the results for just founders:

In both cases, India and China were both underrepresented relative to their share of total H-1B beneficiaries. By contrast, the United Kingdom, Canada, and France were all overrepresented to varying degrees. Not a good start for the advocates.

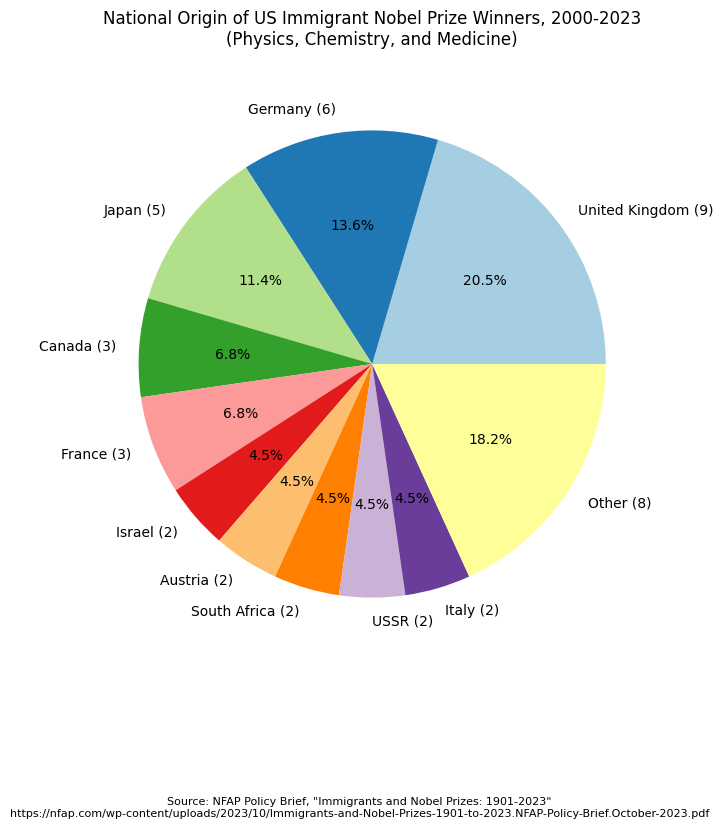

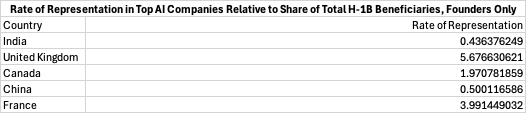

Next up is the screenshot with a heading noting that immigrants have won 40% of Nobel prizes since the year 2000. I already pointed out to Alec on X/Twitter that he should probably read his own source first because it’s once again not a good look for him. Just from eyeballing the tables, one can already tell it’s largely European and Anglosphere countries with a generous sprinkle of East Asian. For easier visualization, another writer who goes by “Arctotherium” was kind enough to produce the pie chart version.

The irony here is that India did not even have a single person here on the list, while China had just one. India is consistently the largest beneficiary country of H-1B visas while China is the second largest. However, between China and India, the difference in the number of approved petitions isn’t even close, so in reality, it’s mostly just India gaming the H-1B system. European and Anglosphere countries each produced slightly over 38.6% of all immigrant Nobel prize winners for a total of nearly 77.3%. Anyone else starting to notice a pattern here?

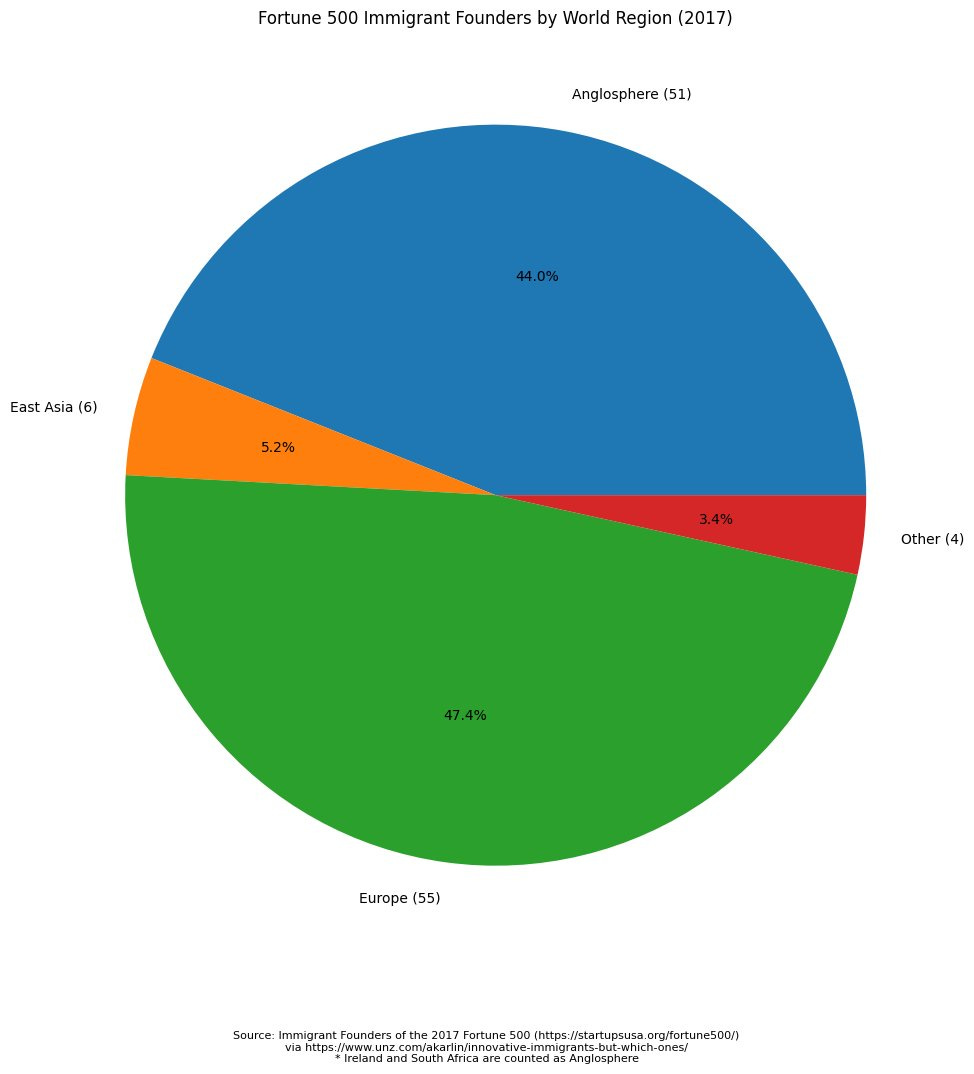

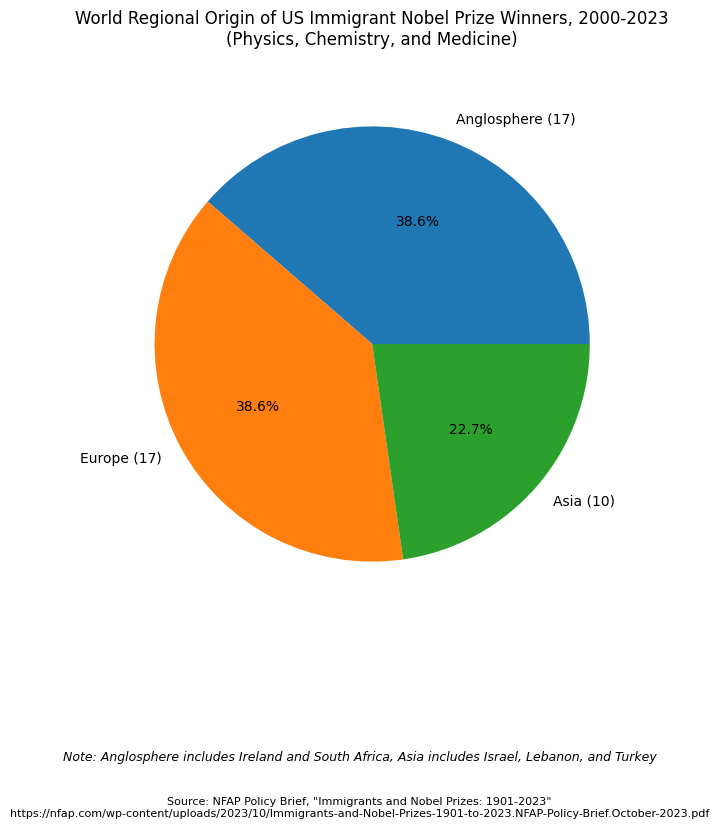

So, the statistic afterwards is the much beloved and commonly cited one that immigrants made a disproportionate contribution in founding Fortune 500 companies. This is a bit dated but in 2017, the Center for American Entrepreneurship released a detailed analysis of the demographics of the founders, and it’s remarkable how European and Anglosphere overrepresentation keeps showing up over and over again. For ease of visualization, here’s the result as pie charts once again:

It’s unlikely that much has changed since then. Of course, if you have evidence that will prove me wrong, by all means, but this would be pretty consistent with all the other measures of innovation so far, so I doubt it.

Lastly, the final image from Alec says that immigrants founded more than half of unicorn companies. Again, the National Foundation for American Policy is kind enough to provide us with the place of origin of the founders (Anderson, 2022, Table 5). As with top AI companies, I compared the same countries relative to their share of total H-1B beneficiaries but with the cutoff year at 2022 instead of 2023, and lo and behold, would you guess what the results are:

India is the most underrepresented, followed by China, while the United Kingdom, Canada, and France are overrepresented to varying degrees. Again, it’s incredible how remarkably consistent these findings are.

So, TL;DR—here’s a table showing the rate of representation among those five countries compared to their share of H-1B beneficiaries for each of these measures of innovation:

All of this also corroborates with Nager et al. (2016) which measured innovation via R&D awards and triadic patents for large tech companies, life sciences, information technology, and material sciences. When looking at the foreign-born population, Europeans and Asians are both extremely innovative, but Europeans especially so—with a rate of representation of 8.2 vs. 4.5 for Asians.

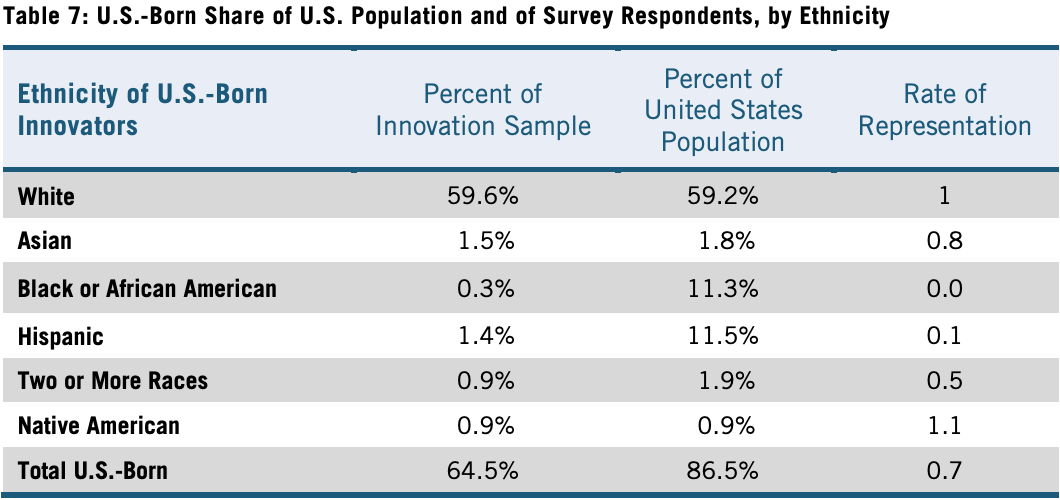

The innovation rate is greatly reduced in the native-born, but among them, whites are still more innovative than Asians:

Given that India is the largest beneficiary of H-1B visas but underperforms so severely compared to European migrants, it’s entirely a fair question to ask why exactly certain people seem so eager to bring more of them over. If you genuinely care about skilled legal immigration, an expansion of the current system is a terrible way to go about doing so (see Arctotherium, 2024a; Whitfeld, 2023). With regards to Indian immigrants in particular, they are essentially a hostile elite in the making that will destroy the very same values that made the United States so successful in the first place, and any economic gain from having them in the country will diminish the more that are admitted (Arctotherium, 2024b). Either massively reform the current system or stop pretending like the goal is about recruiting “high-skilled immigrants”, that is evidently not the case.

Addendum

Arctotherium was kind enough to help me produce some additional pie charts. Here is the national origins of immigrant unicorn companies based on the 2022 report from the National Foundation for American Policy:

Some people were complaining that I used the share of H-1B beneficiaries as my method of comparing countries because they claimed that only being on a temporary work visa and not being able to actively participate if one were to create a new company disincentivizes innovation. This seems like a bizarre post-hoc rationale to dismiss evidence they don’t like. Are we just going to pretend that the Christmas War on X/Twitter wasn’t precisely about H-1Bs and that the advocates didn’t defend an expansion of the current system precisely by appealing to these sorts of measures? But fine, I am willing to entertain this since we can use national shares of immigrant STEM workers instead. There is a 2022 report from the American Immigration Council which covers the year 2019 (a more recent one has yet to be released so we’ll have to make do) and this is the breakdown:

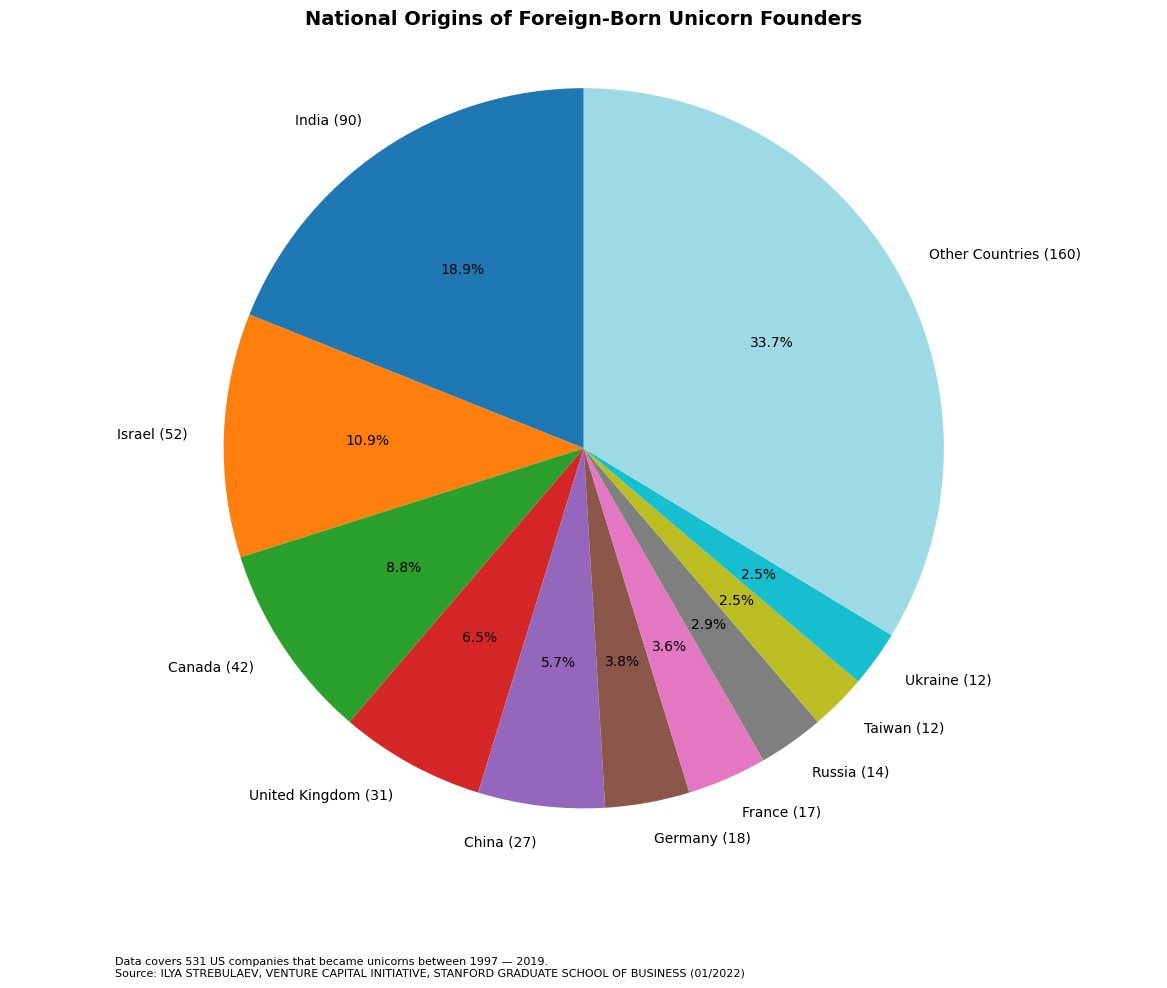

India made up 28.9% of total migrant STEM workers in 2019 but just 17.4% of unicorn companies. So, India is still underrepresented. There is also another analysis from the Stanford Graduate School of Business which looks at immigrant unicorn founders from 1997-2019 and guess what? India is indeed still underrepresented:

Now, it’s not shown here, but I quickly added up all European countries and they totaled ~21.28% of all the immigrant founders of foreign-born unicorn companies, so they are more than punching above their weight. Anglosphere countries came in at ~16.38%, but remember they make up a much smaller share of all migrant STEM workers, given that Canada has the largest share among them which is only 2.2%, so they are also punching above their weight. So, as it turns out, all those criticisms amounted to basically nothing.

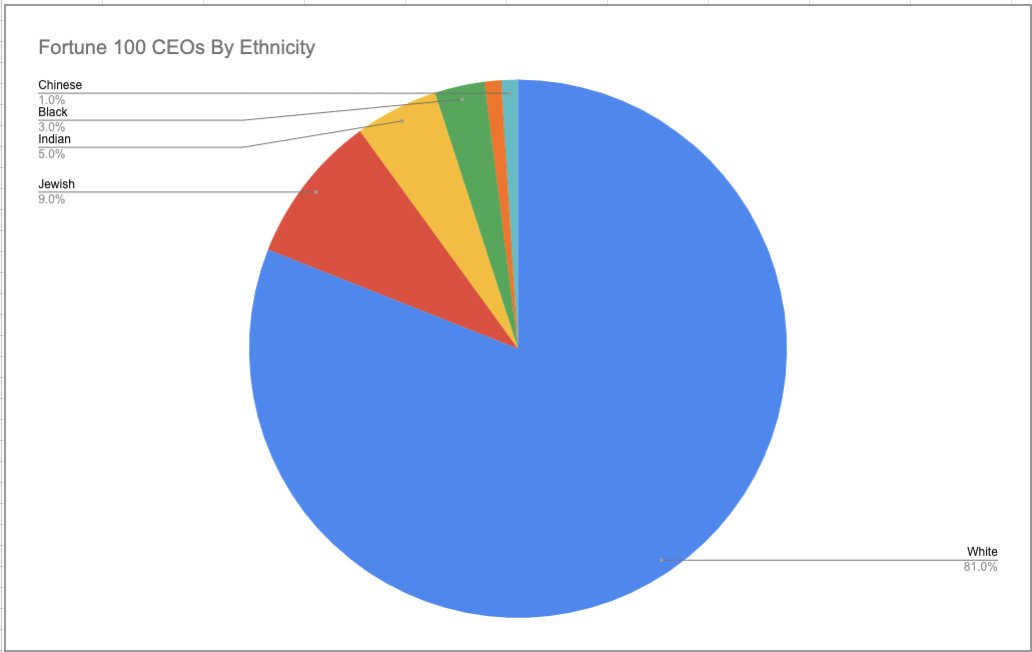

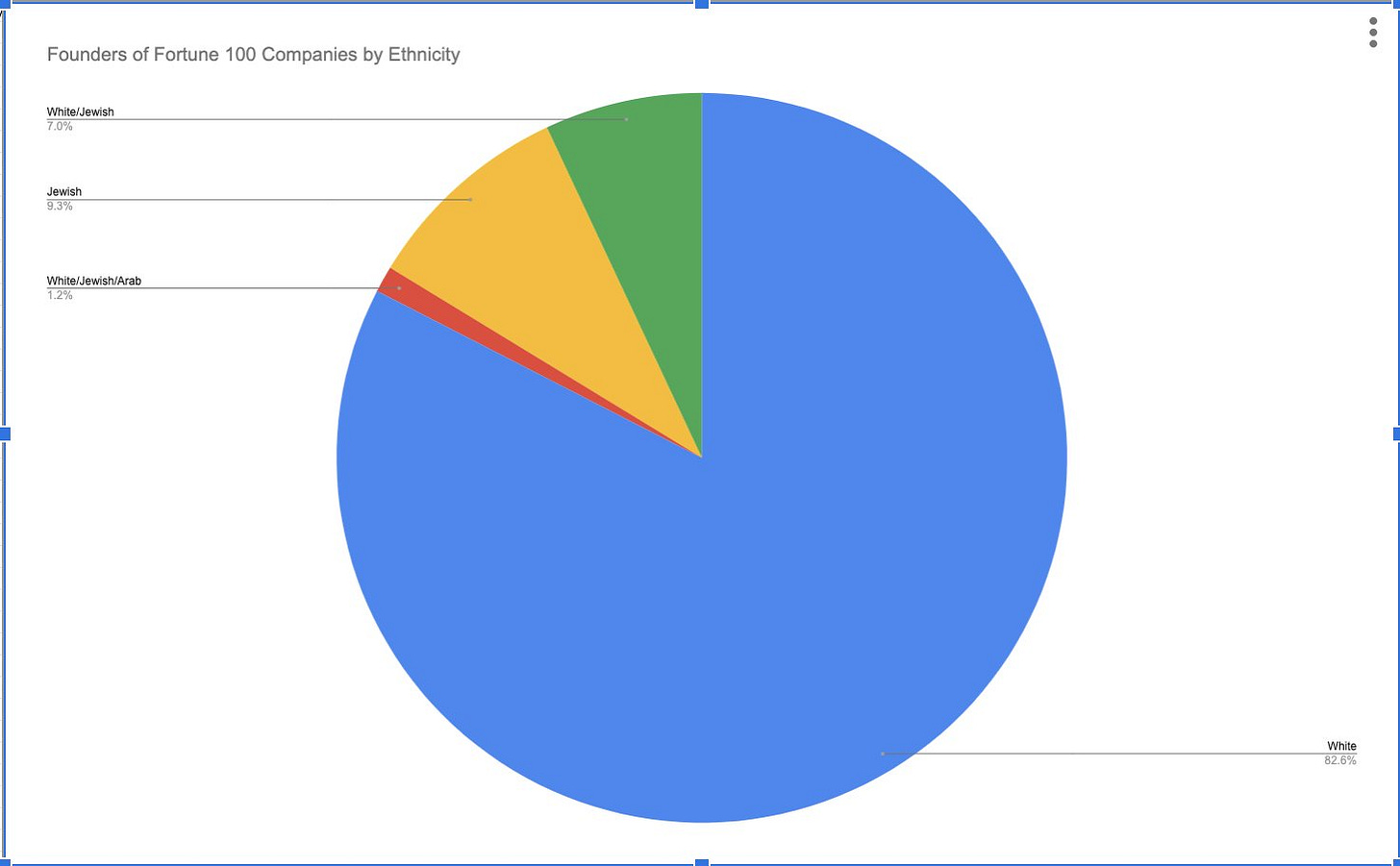

Alright, now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, have a few more pie charts to finish off. Here’s the ethnicity of Fortune 100 CEOs and founders:

Yep, extremely white. Fortune 200s meanwhile aren’t even disproportionately founded by migrants. In fact, it’s overwhelmingly founded by natives, so the point about high-skilled immigrants doesn’t even work here:

So, what’s the takeaway here? True talent that can enrich the United States comes from other Europeans, both immediately and in the long run for future generations. There is no “top talent” that we desperately need from India, the United States will not lose its number one spot if it doesn’t expand the current legal immigration system so that more Indians can get through. The only reason why pointing out this reality is considered wrong is because it serves as a constant reminder to insane advocates that a truly meritocratic society would be one that is whiter than the current United States and nothing like their delusional wet dreams of a multiracial utopia.

If Richard Hanania had any honor (impossible for a Semite) he would rope after reading this.

Look if America winning is the American worker living under worse and worse conditions, then I want America to lose, and lose hard