The Truth About Lie Detectors

And do they actually work

Until the last two decades, it was conventional wisdom among the general public that the lie-detector, more technically referred to as the polygraph, was almost perfect (National Academy of Sciences, 2003). A national survey of over 1,500 adults, conducted in 1986, found that three fourths believed that those accused of crimes should be given lie detectors (Horvath, 1987). Indeed, lie detectors were so common back then that 15% of respondents in the same survey reported having been examined by one. However, reviews of experts looked slightly different. Iacono & Lykken (1997) summarized results from two surveys of members of the Society for Psychophysiological Research, both of which found around 60% agreement with a statement to the effect of the polygraph being “a useful diagnostic tool when considered with other available information.” Almost zero respondents, on the other hand, believed that evidence from the polygraph in itself was enough to prove that someone was lying, and between a third and about 40% believed that it was “of no usefulness” or “of questionable usefulness.” Iacono & Lykken conducted their own survey, and found similar results for the same type of question (though slightly less favorable to the polygraph). More interesting were their results for a question asking respondents if they believed the comparison question test (CQT; the most common type of polygraph examination) was more than 85% accurate; only about a fourth of experts agreed with this statement. When a similar question was asked of a lay sample of Californians, agreement with the statement was closer to two thirds (Myers et al., 2006). Of those who could provide an estimate, the average was about 60%, which is not much better than chance.

However, the public soon caught up to the experts. Although no recent surveys have been conducted (to my knowledge), it seems that very few believe them to be accurate. I’ve asked people in several conversations during the process of researching this topic if they knew anything about lie detectors, and, invariably, the first thing that I was told was that they don’t work. This view is expressed by a lot of popular science media, and seems to go unquestioned. For example, the Smithsonian recently published an article titled “Why Lie Detector Tests Can’t Be Trusted,” where no studies were cited, and the only evidence consisted of a few anecdotes from the Cold War, in which it is not even known that the lie detectors’ results were incorrect. However, there are several recent reviews which, though sometimes critical, admit that the polygraph has a very high accuracy.

Synnott et al. (2015), for example, published a mostly harsh summary of polygraph research in the journal Crime Psychology Review. Despite its mostly negative tone, however, the article ends on a positive note (p. 76):

In its current state, the polygraph can already serve as a viable investigative tool to investigators, and its value is likely to increase as research continues to improve and address its current shortcomings…. While it may not be possible to improve the polygraph to the level where it can truly be thought of as ‘The Lie Detector’, it does appear to hold the potential of becoming one of the most effective tools for the purpose of aiding investigators in the detection of deception.

Whether or not experts today are more positive about the polygraph than they were thirty years ago is not possible to ascertain, as I am unaware of any recent surveys of psychologists or criminologists on this topic. However, the lie-detector apparatus definitely has one thing going for it in this debate: the truth. Despite not being popular among experts throughout most—if not all—of its history, I have been unable to find a large-scale, quantitative review of polygraph validity studies that reports an accuracy below 80%, let alone as low as 60%. Even in the most critical literature review, which was itself an analysis of a few other, mostly small literature reviews, the accuracy rate for guilty suspects was about 85-90%, while the accuracy rate for innocent suspects was 60-70% without removing inconclusive results (Vrij, 2008, Table 11.3)—considerably better than chance.

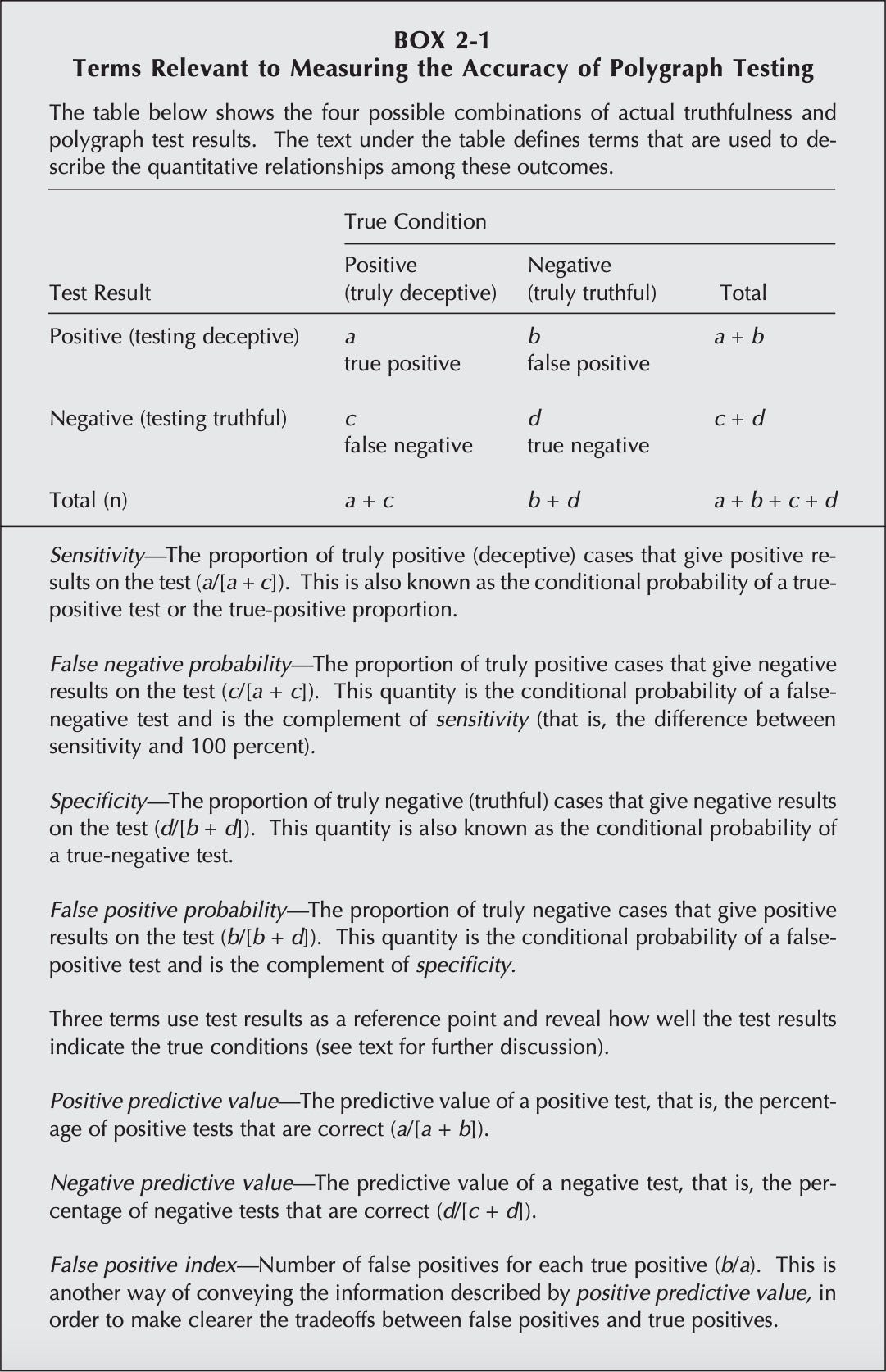

Below, I have included every major meta-analysis of the lie-detector’s validity that I could find. The measures used (don’t worry, a table below contains all of the following information) in this post are overall accuracy (% of results that are correct when inconclusive ones are removed), false positive and negative rate (% of cases that are incorrectly considered positive and negative, respectively, when inconclusive ones are removed), positive and negative predictive value (% of positive and negative results, respectively, which are, in fact, positive and negative, respectively), sensitivity and specificity (% of those who ought to be positive and negative, respectively, which test positive and negative, respectively), and area under the curve (this is a complex measure and is only used in one study). A helpful image explains how all of these are calculated (from National Academies of Sciences, 2003, p. 38; not all of these are used in this post):

Whenever possible, I will use meta-analytic results for field studies (those conducted using actual suspects where guilt or innocence was not known at the time of their taking the test), and only when the CQT is used, as that is by far the most popular version of the polygraph examination. For a full overview of this method, one should go elsewhere (National Academy of Sciences, 2003; Synnott et al., 2015), but a basic explanation is still given here. This method consists of the examiner asking a series of questions, some of which are not relevant to the case (e.g., “is today Friday?”), and some of which are. The irrelevant questions are used to calculate the baseline physiological statistics, to which bodily responses to the relevant questions are compared.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Heretical Insights to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.