Does the Minimum Wage Decrease Employment?

And a few other considerations

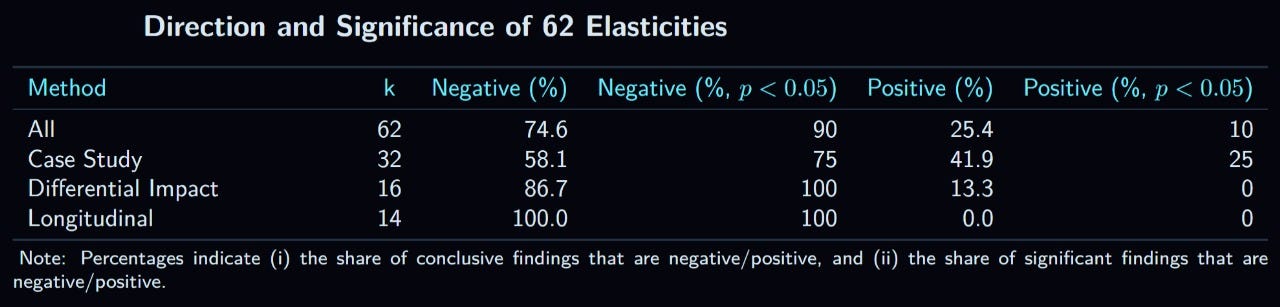

CONTENTS

2.1a. The Case Study Method: U.S. Studies

2.1b. The Case Study Method: Studies Outside the U.S.

2.1c. The Case Study Method: Synthetic Control Studies

2.1d. The Case Study Method: Overall Summary

Criticisms of the Time-Series Literature

3.1. Publication Bias

3.2. The Method Itself

3.3. Time-Series Using State-Level Variation

3.4. Summary

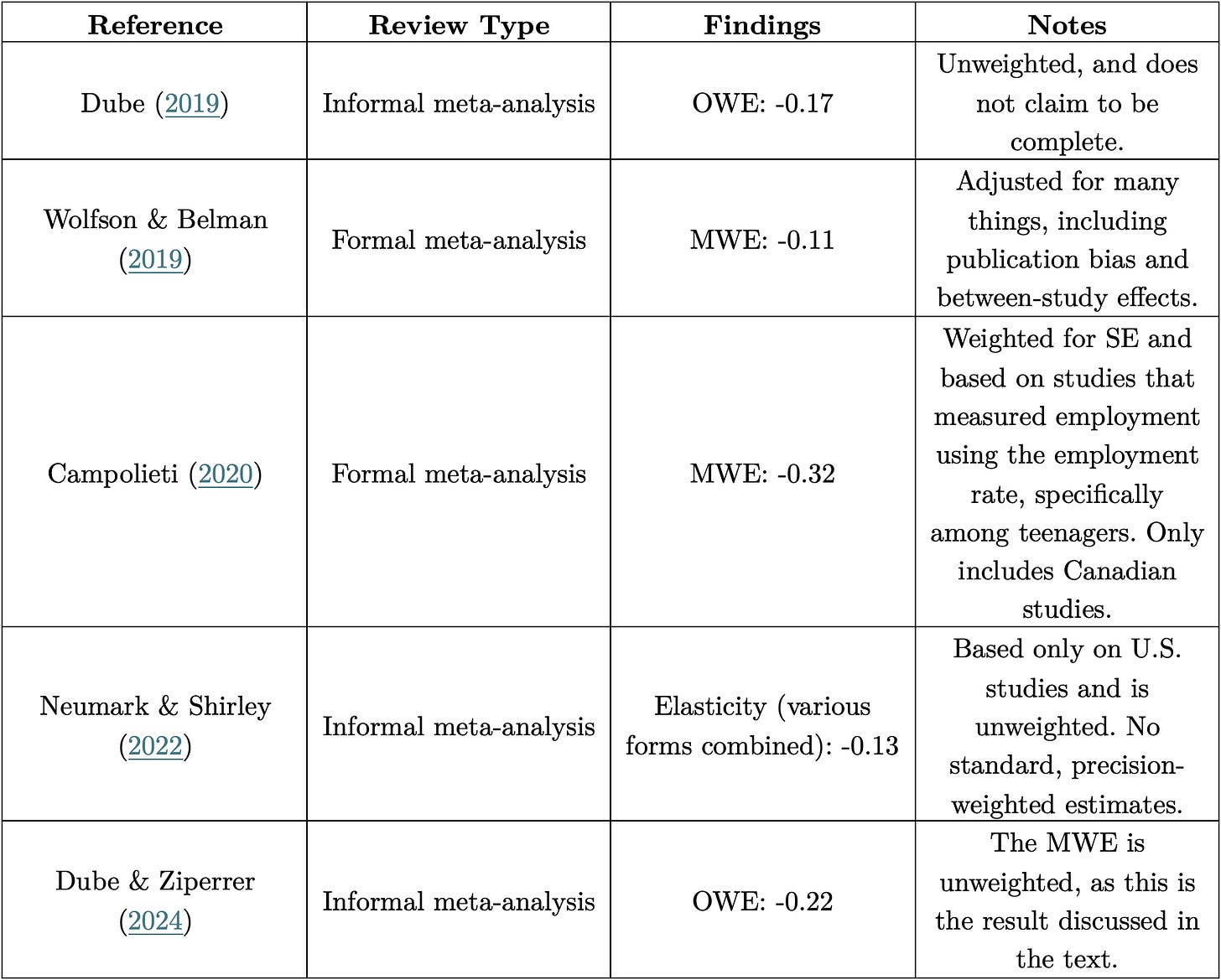

4.1. Dube (2019)

4.3. Campolieti (2020)

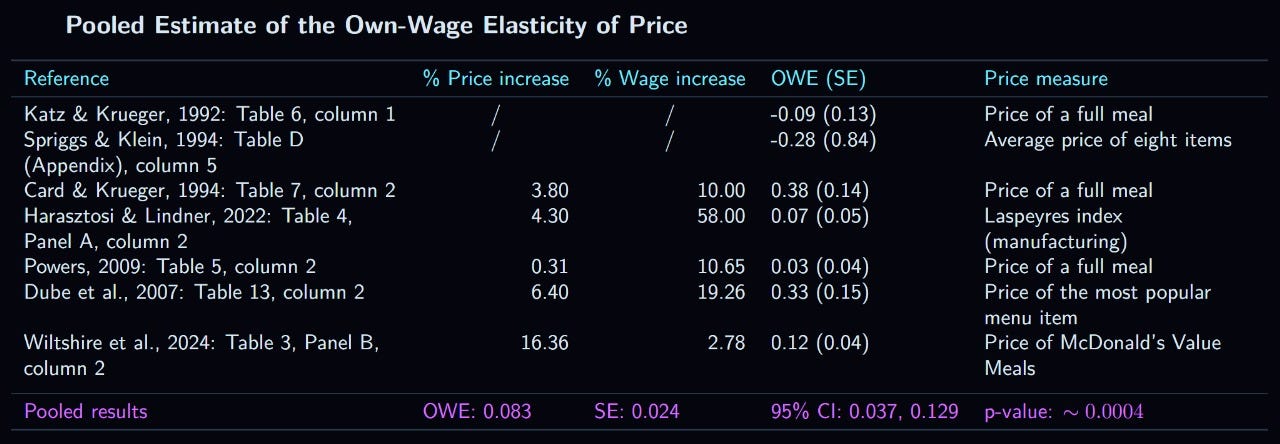

5.1. Price

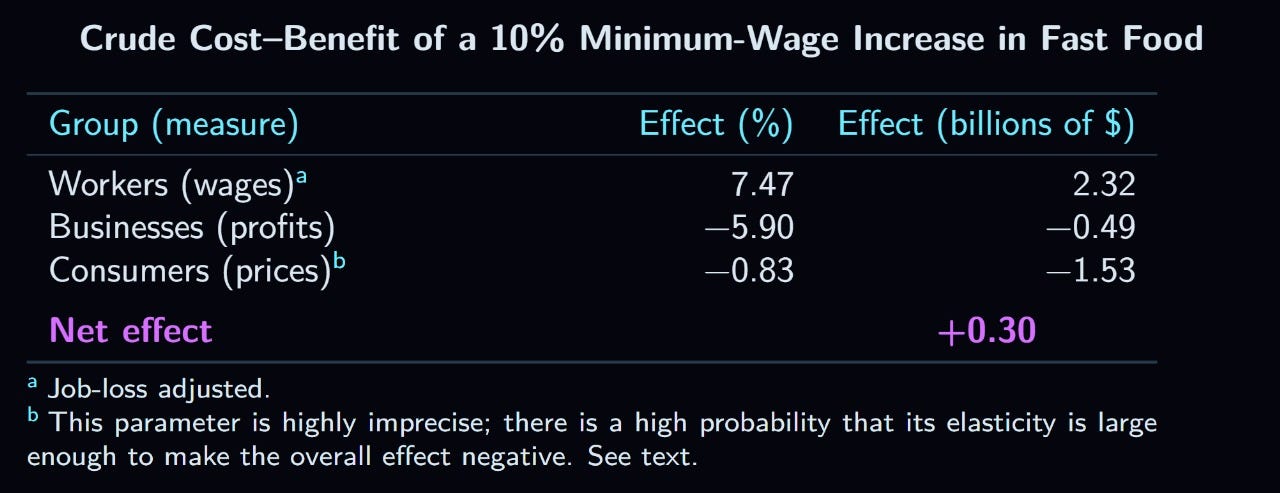

5.2. Profits

5.3. The Answer

6.1. Summary

6.2. Conclusion

Note: All of the tables and figures in this post were created by Ben Alfred (X/Twitter link).

1. Introduction

In the late 19th century, New Zealand became the first country with a national minimum wage law; by the early twentieth century, the classical economic theory of how the minimum wage affects employment had already been developed. The simplest logical demonstration that the minimum wage reduces employment is that it increases wages, which must in turn reduce the profit gained from labor, and, because demand has a negative elasticity with respect to price—i.e., people want less of something if it becomes more expensive, ceteris paribus—labor would have to decrease. It was not until the mid twentieth century, however, that a large empirical literature on the question of how minimum wages affect employment was developed. In 1977, the Minimum Wage Study Commission collated and reviewed the studies published up to that point, concluding that the elasticity of labor demand from these studies was between -0.1 and -0.3, but probably closer to the lower end of the range (Brown et al., 1982). This meant that if a minimum wage increase raised wages of some group of workers by 10%, their employment would fall by 1 to 3 percent. This became known as the “consensus view” (Neumark & Wascher, 2008, chapter 2).

However, beginning in the early 1990s, some economists criticized this view,1 claiming that it was based on studies which are not very informative due to severe methodological flaws. These researchers argued that, instead, different methods should be used, and the old methods ought to be discarded. The movement had its biggest breakthrough with the publication of David Card’s and Alan Kruger’s Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage (1995), which concluded that the best estimates of the elasticity of labor, based on minimum wage case studies, show null or positive effects. I refer to the literature that had its origin in this movement “the New Economics”.

Today, there are, broadly, three schools: Economists who believe that the new literature is mostly consistent with the classical studies (e.g., David Neumark and William Wascher); those who believe that the theoretical prior for labor having a negative elasticity is so strong that the empirical literature essentially cannot be convincing if it does not align with the prior (e.g., Bryan Caplan); and, lastly, those who believe that the new studies disagree with the old ones, and convincingly so, such that there is no negative impact of the minimum wage on employment—that is, the New Economics (e.g., David Card and Alan Krueger). Here, I support the argument made by the first group, though I am not necessarily against the idea of theory being given more weight than empirics.

The structure of this article is as follows. This section introduced the issue; the second will summarize the empirical literature using an informal meta-analytic technique based on the three types of studies promoted by the New Economics. Section three briefly summarizes the debate about the oldest type of study in this field, namely, the time-series. Next, the fourth section discusses several recent reviews that examined similar studies as what I looked at in section 2. In the fifth section, I conduct a crude cost-benefit analysis by first calculating the elasticities of product prices and of business profits, and see the hypothetical changes in dollar terms for the fast food industry (in terms of workers’ wages, business profits, and prices) of a minimum wage spike that would increase nonsupervisory workers’ average wages by 10%. Lastly, section 6 discusses my findings and concludes. This post includes also two appendices. Appendix A compares my estimates to a recent review to see how we treated the studies common to both analyses, while Appendix B has some basic recommendations for what to read and watch to learn more about the empirical minimum wage literature. I would recommend most readers to only skim section 2, and only especially pay attention to the summaries, but to read every other section attentively.

2. Empirical Evidence

There are several ways to study the effect of the minimum wage on employment within the New Economics. These methods will be analyzed in order from most to least commonly used.

2.1. The Case Study Method

This section reviews the body of case studies that exploit discrete minimum-wage increases as natural experiments to estimate employment effects. Each study follows the same basic strategy: identify a jurisdiction that enacted a wage hike, select an appropriate comparison group that did not experience the increase, and track the relative change in employment before and after the policy shift. Although the specific designs vary—some compare bordering states or cities, others compare low- and high-wage groups within the same region—the underlying logic is consistent: differences in employment trends between the treatment and control groups provide an estimate of the minimum wage’s causal impact.

2.1a. The Case Study Method: U.S. Studies

This subsection examines the large set of minimum-wage studies that use case-study or event-study designs, in which the employment effects of a specific minimum-wage “spike” are evaluated by comparing the affected area to a suitable control. These studies typically analyze a single state, city, or region at the moment its minimum wage rises, and then estimate the causal effect by contrasting subsequent employment changes with those in a location that did not experience an equivalent increase. Because these natural experiments have been conducted in many settings—across multiple U.S. states and cities, as well as in several other countries—they provide a diverse set of quasi-experimental estimates. I will present these case studies, explain the methodological debates surrounding each, and assess what conclusions can reasonably be drawn from this body of evidence.

2.1a.1. New Jersey, 1992

I start this review by examining what is by far the most famous study that used this methodology, which was published by David Card and Alan Krueger (1994). While the rest of section 2.1a is in chronological order, I believe that making an exception here is necessary to best introduce the method.

In April of 1992, New Jersey increased its minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05. To estimate the impact of this increase, Card & Krueger conducted interviews throughout February and March of the same year in 410 fast-food restaurants from the following chains: Burger King, KFC, Roy Rogers, and Wendy’s. Of these restaurants, 331 were located in New Jersey, while another 79 were in Pennsylvania. The latter group served as the most important control, because Pennsylvania did not experience a change in its minimum wage in that year. An alternative control group, also used by Card & Krueger, was made up of New Jersey restaurants which had starting wages higher than the new minimum wage, as these were presumably not affected by the increase. Almost all restaurants were reinterviewed in November and December of the same year, three quarters of a year after the increase in minimum wage; the total sample size for the second wave was 321 for New Jersey and 78 for Pennsylvania. The employment measure was the number of full time equivalent (FTE) workers, which differs from the standard measure only in that it weighs part time employees at half the value of full time employees (i.e., one part time employee=0.5 FTE workers).

Card & Krueger found that, during this period, FTE employment decreased in Pennsylvania, while increasing slightly in New Jersey. This suggests an increase, rather than a decrease, in FTE employment due to minimum wage! The effect of minimum wage is also positive when comparing restaurants within New Jersey which had different starting wages at the initial interview. Those restaurants with starting wages above $5 saw a decline in FTE employment, while those with wages below the new minimum saw an increase. The conclusion of this study was that the increase in minimum wage did not lead to lower employment, but, if anything, lead to its increase.

However, there was one major issue with the study: it relied on interviews to estimate the number of FTE workers at a restaurant, which proved to be a highly volatile, noisy measure due to misinterpretations by the interviewee. Neumark & Wascher (2000) attempted to replicate Card & Kreuger’s study using payroll records for the same restaurants in the same zip codes, during the same two periods (i.e., February to March and November to December). Contrary to the original study, Neumark & Wascher found no change in the number of FTE workers in Pennsylvania, but a large decrease in New Jersey—the opposite effect.2 Because data regarding starting wages were not collected, a replication of that aspect of the study could not be attempted.

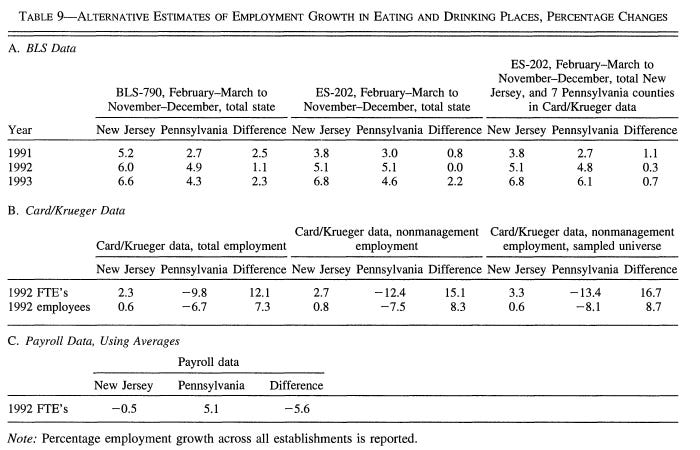

As another test, these researchers also used BLS data to see if the decline in New Jersey and Pennsylvania would be noticeable in state-level employment changes between 1991, 1992, and 1993, for the restaurant industry in general. The rate of growth was approximately the same for New Jersey and Pennsylvania in all three years, which, while it technically does not support either study’s findings, is much more damning for Card and Krueger. This is because Neumark & Wascher found very small changes (+5% growth in Pennsylvania, and -0.5% in New Jersey), while Card & Krueger found very large changes (-10-13% in Pennsylvania and +2-3% in New Jersey). The table below summarizes the three different lines of research: the government collected employment data, Card & Krueger’s estimates, and Neumark & Wascher’s estimates.

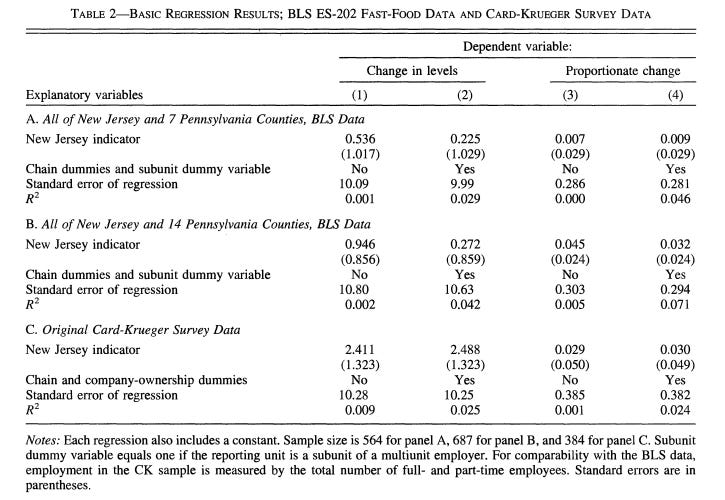

Card & Krueger (2000) published their reply in the same issue of the American Economic Review. They began by analyzing a new dataset, which consisted of BLS data for individual fast-food restaurants for the same counties as examined in their original study (and, by extension, in Neumark & Wascher’s), with the addition of seven more counties in Pennsylvania. Their results are best depicted in the following table:

These effects are small and not even close to being statistically significant. The best estimate from this study (0.225 additional employees due to the increase) is a tenth of the best estimate from the original study (2.49 additional employees).

The next part of Card & Krueger’s response was a reanalysis of Neumark & Wascher’s data by constructing their own, more complete dataset. They found that Nuemark & Wascher’s sample was not random, and, specifically, biased toward inclusion of businesses with lower growth rates over this period. When Card & Krueger replicated their results, and added some controls, the results were no longer significant, and the effect size was miniscule. Furthermore, when they restricted the sample to the 48 fast-food restaurants in Neumark & Wascher’s sample which they could match with restaurants in their own sample, the results showed either no change or a slight increase in New Jersey employment relative to Pennsylvania.

Based on what they wrote in their book Minimum Wages (2008), Neumark & Wascher seem to accept Card & Krueger’s conclusion that the best evidence indicates that the rise in minimum wage in 1992 had a small and insignificant effect on New Jersey employment relative to Pennsylvania. So, to summarize, Card & Krueger originally concluded that there was a huge increase in employment due to the minimum wage; then, Neumark & Wascher conducted their own analysis, finding a small negative effect; finally, Card & Krueger conducted a superior analysis of a more complete version of the same data, and found that there was no significant effect, to which conclusion Neumark & Wascher seem to have agreed.

2.1a.2. California, 1988

In 1988, the Californian minimum wage rose from $3.35 to $4.25, which affected approximately half of all teenagers due to their wages being lower than the new minimum. Card (1992a) analyzed data for teenage employment in California alongside several bordering states between 1987 and 1989, who were not affected by any minimum wage increases during this time. Card estimated that the wages of teenagers living in California increased by about 10% during this period relative to the same demographic in the control group. The effect on employment was an increase of 5.6%, which was statistically significant (p<0.02). Once again, this early study actually found a positive effect of the minimum wage!

Kim & Taylor (1995) attempted to replicate these results by examining the retail industry specifically. The comparison group was the rest of the U.S. rather than just the states bordering California. While focusing on a specific low wage industry is probably better than examining all teenage employment,3 the control group is likely inferior to the one used by Card. Kim & Taylor estimated the impact of the minimum wage by finding the effect of the difference between the change in the average wage of an industry in California versus the rest of the U.S. The coefficient for this variable, which was equal to about -0.9 (two different models with roughly the same effect size, both p<5 × 10-8). This is in sharp contrast to Card’s estimated elasticity of over +0.5. It should be noted that Taylor & Kim also confirm their estimate by examining the effect of the Californian minimum wage increase by exploiting the fact that its effect would have been larger in magnitude for locations with initially lower average wages (this type of study will be examined in detail in 2.3). Their confirmation shows a similar elasticity of about -0.7 (p<0.001).

In their book, Card & Kruger (1995, pp. 101-108) criticize Kim & Taylor’s methodology, claiming that the disparity between Card’s and Kim & Taylor’s result is caused by measurement error in the data used by Kim & Taylor, which, given their specification, biases results toward -1 rather than 0. The reason for this is that average wage per worker was computed by dividing the total amount of wages paid in the first quarter of each year by the number of people earning a wage on the last day of March. This means that employment as of March 31st is mechanically negatively correlated with the average wage. In the original paper, Kim & Taylor found that there was often a highly negative correlation between their wage and employment change variables in most of the models for the year-long periods leading up to the minimum wage increase, though these were never significant, except for in one model for 1985-86, where the effect size was much smaller (-0.361). Card & Krueger analyzed the data for 1989 to 1990 using Kim & Taylor’s method, & found that these were negative, too, though, as Neumark & Wascher (2008, p. 303, n. 31) noted, these could have been caused by “a lagged effect from the 1988 increase”.

Most important was the reanalysis by Card & Krueger of the California increase’s effect, using the same DiD approach as employed by Card (1992a), but looking at workers in the restaurant and retail industries, rather than all teenagers in the state. The control group was, once again, restaurants in states bordering California, who did not experience a change in their minimum wage. For the retail industry, the DiD effect sizes, for comparisons of 1987 vs. 1989 and 1988 vs. 1989, were -1.26% and -0.29%, respectively. For restaurants, the same figures were +0.04% and -1.91%. Unfortunately, standard errors were not presented, so it is not possible to test for significance. A reduction of around 1% in employment would correspond to an elasticity of -0.12 for the restaurant industry (for the change in wage, see Table 3.6) and -0.20 in retail.

Lastly, I should note that Kim & Taylor’s analysis of the differential impact of the minimum wage across counties has also been criticized, and, in this case, whether or not there is a major problem is not ambiguous (see Kennan, 1995). However, this was never their primary measure, and also isn’t the subject of section 2.1.

2.1a.3. Texas, North Carolina, and Mississippi, 1991

Two studies examined the effect of the 1991 federal minimum wage spike to $4.25 an hour using the case study approach, and they reported their basic results in terms of elasticities. Katz & Krueger (1992) studied the impact on Texas by seeing if businesses more impacted by the minimum wage—because their starting wages were further below it—experienced different changes in employment afterward. They found that the fast food restaurants more impacted by the increase actually had an increase in both overall and FTE employment. The results, in terms of elasticity, were +1.73 (insignificant) and +2.48 (significant). As far as I am aware, these findings have not been challenged, unlike the other Krueger/Card studies.

Using basically the same method, Spriggs & Klein (1994), looked at two cities, one in Mississippi and the other in North Carolina. Their estimated elasticity was much lower (+0.062) and was nowhere near statistical significance.

2.1a.4. Pennsylvania, 1996-1997

In 1996, the federal minimum wage was increased to $4.75, and then in 1997 to $5.15. Recall that, in the most famous case study, the event was an increase in the New Jersey minimum wage to $5.05, relative to Pennsylvania, whose minimum did not change. When the federal increase occurred, the Pennsylvania minimum increased by $0.90, while New Jersey’s only increased by $0.10, the two states now being completely equal. This fact was used by Hoffman & Trace (2009) to explore the impact of the minimum wage on employment, this time using Pennsylvania as the treatment group, and New Jersey as the control. Their effect size estimate was an insignificant decline in teenage (16-19) employment of 3.76%.

2.1a.5. Illinois, 2004 & 2005

In January of 2004, Illinois raised its minimum wage from $5.15 to $5.50, and then to $6.50 a year later. This natural experiment was studied by Elizabeth Powers, Ron Baiman, and Joseph Persky in an unpublished report to the Russell Sage foundation. The authors of the report have published assessments of their findings, disagreeing in their interpretation of the facts. The design of the study was very similar to several of the other studies reviewed thus far: interviews were conducted at three separate times, before and after each increase, with Arby’s, Burger King, KFC, McDonald’s, Subway, Taco Bell, and Wendy’s restaurants in Illinois as well as in the control state, Indiana.

Powers (2009) was the first to describe the results of this study publicly. The main analysis was made up of a comparison between the first and third waves, as the second wave affected only about one third of the restaurants sampled (because most restaurants already had starting wages above the new minimum). Powers found a marginally statistically significant (p<0.1) reduction in FTE workers4 in Illinois compared to Indiana when comparing 2003 and 2005 interview data, and a statistically significant negative effect when comparing 2004 and 2005 in a supplemental analysis (Table 6). The losses were equivalent to about a reduction of 3 FTE workers, or, in relative terms, a drop by roughly 25% based on the 2003 baseline. Powers concluded that these data showed that the minimum wage has a strong negative effect on employment.

Persky & Baiman (2010) disagreed with Powers’ conclusion. They calculated a decline in Illinois relative to Indiana of either 0.88 or 3.1 FTE workers, depending on how an FTE worker was defined. The former figure represents the number of FTE employees as calculated in the same way as Card & Krueger (i.e a worker categorized as part time by the interviewee is counted as 0.5 FTE workers), while the latter is calculated in the same way that it was calculated by Powers, based directly on hours worked (see my fn. 6). The decline in the Card-Krueger definition of FTE employees was not significant even at the ten percent level, while the second definition was significant at the five percent level. The latter definition is preferable because it is a purer measure of hours, which is how labor is typically defined in employment schedules. So far, the results are concordant with those reported by Powers. However, Persky & Bainman also reported that adding a covariate for length of the pay period reduced the decrease in the second type of FTE worker to 1.9 workers, which made it no longer significant, though still large in magnitude.

2.1a.6. New York, 2004 & 2006

In 2004, the minimum wage in the state of New York was $5.15, which number increased to $6.75 in 2006. The first researchers to study this spike were Joseph Sabia et al. (2012). The comparison group consisted of three states: Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New Hampshire. The measure of employment was the employment rate of teenagers (aged 16-19) without high school degrees. The DiD estimated decline in the best model (Table 3, column 6) was 7.2 percentage points, or a relative decline of a little over twenty percent. This decline was just barely statistically significant (p= ~0.046).5 The later investigations of this minimum wage increase are discussed in section 2.1c.

2.1a.7. San Francisco, 2004

Near the end of 2003, a law passed in the city of San Francisco increased minimum wage to $8.50 an hour, which was a 26% increase to the previous minimum of $6.75. The law took effect in February, 2004, and its impacts have been analyzed by Dube et al. (2007), who used the East Bay area near the city as a control. The total sample consisted of around 200 restaurants from San Francisco and roughly 100 from the East Bay.6 Most of the effect sizes for both the total number of employees and the number of FTE workers were positive (implying that minimum wage had a positive effect on employment), but none were significant at even the 0.1 level, despite being somewhat large.

2.1a.8 Santa Fe, 2004 & 2007

In mid 2004, the minimum wage in Santa Fe (New Mexico) increased from $5.15 to $8.50, and, in the begininng of 2007, up to $9.50; thereafter, the minimum wage was set to be adjusted for shifts in the cost of living. Justin Hollis (2015) explored the effects of these increases on low wage workers, from 2004 to 2012, using the city of Albuquerque as a control, because the minimum wage in Albuquerque did not change nearly as much during this period (from $5.15 in 2004, to $6.75 in 2007, with small increases thereafter). Low wage workers were defined as those in occupations where employees at the 75th percentile earned less than the 2004 minimum wage in 2003. In terms of total employment in these industries, there was an insignificant decline of 12.54% in the first increase (i.e., in 2004), and of 24.50% in the second (i.e., 2007). However, the first decrease is difficult to interpret, as the change in income was only marginally significant (p<0.1).

2.1a.9. Six Cities, 2009-2015

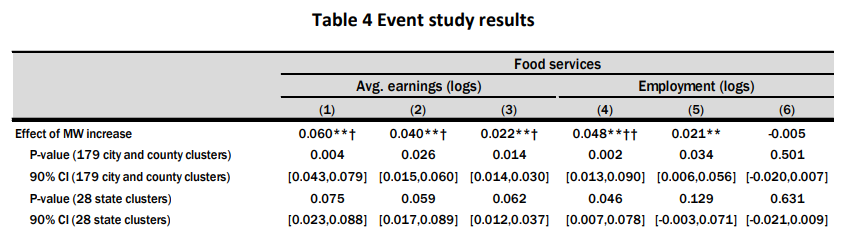

Allegretto et al. (2018) examined the effects of the changes in minimum wage in the following cities: Chicago, D.C, Oakland (California), San Francisco, San José, and Seattle—each of which had multiple increases over the period under study (2009-2015). A comparison group was used for each city; four comparison groups had no increase during the period of this study, while the other two had no real increase, but still had a nominal one, as their minimum wage was set to mimic shifts in inflation.7 Employment was measured in terms of total number of people employed. The authors summarize their findings in the following table, pertaining specifically to the food service industry (MW=minimum wage):8

The relevant columns are three and six, as these control for population size, private sector size, and the economic trend before the change in minimum wage. These show a decline of about half a percent in employment, though this is not statistically significant (note: to read this table, just multiply the log values by 100, which gives you an approximately equal value in percentage terms).9

2.1a.10. L.A, 2016-2019

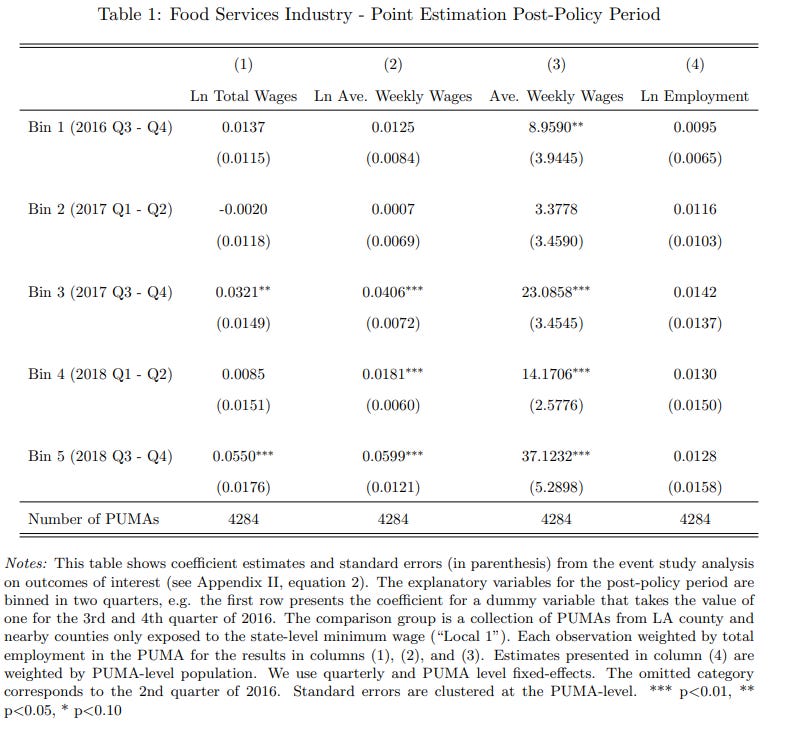

A wage ordinance passed in L.A in 2015 raised the minimum wage several times between 2016 and 2018, and the effects of these increases were studied by Wachter et al. (2020), who used similar locations near L.A as controls. This is their main table:

Each “bin” in the above table represents an increase in the minimum wage. Only two increases resulted in a statistically significant increase in overall wages, and only three in log average weekly wages. Because overall wage is never defined, while weekly wage is (p. 27, fn. 27), and because this is the measure focused on by the authors, I will use this one. In the three rows where the increase in weekly wages was significant, the effect on employment was positive, but never significant.

2.1a.11. California, 2024

Beginning April 1, 2024, California adopted a 20$ per hour minimum wage. The first preliminary report was published in October of the same year (Schneider et al., 2024). It found that there was a tiny increase in average weekly hours in the fast food industry relative to a control group of fast food restaurants in stated whose minimum wage did not change. A second report was published in July of 2025 (Clemens et al., 2025). These researchers found a decrease in employment, seemingly measured as the portion of people employed, of 3.5%.

The most recent report was published in September by Sosinky & Reich (2025). They examined the fast food industry specifically, and the control group was fast food restaurants in states near California who did not have their own increase. They found an employment effect ranging from around -0.8% to +1.2%, representing the portion of the population which is employed at fast food, depending on which quarter one uses. Because this final report uses a weird definition of employment and covers the same time span as the July report, I think that the estimate from the latter should be preferred.

2.1a.12. 288 Minimum Wage Spikes Between 1990 and 2006

Some studies have combined the effects of many events. The first of these was Dube et al.’s (2010) examination of 288 minimum wage changes between 1990 and 2006 among counties that border each other. Put simply, if a state increased its minimum wage, while a state bordering it did not, counties touching each other across that border would be compared. Their effect size in the best model was an elasticity of +0.085 for the restaurant industry, which does not attain anything near significance.10

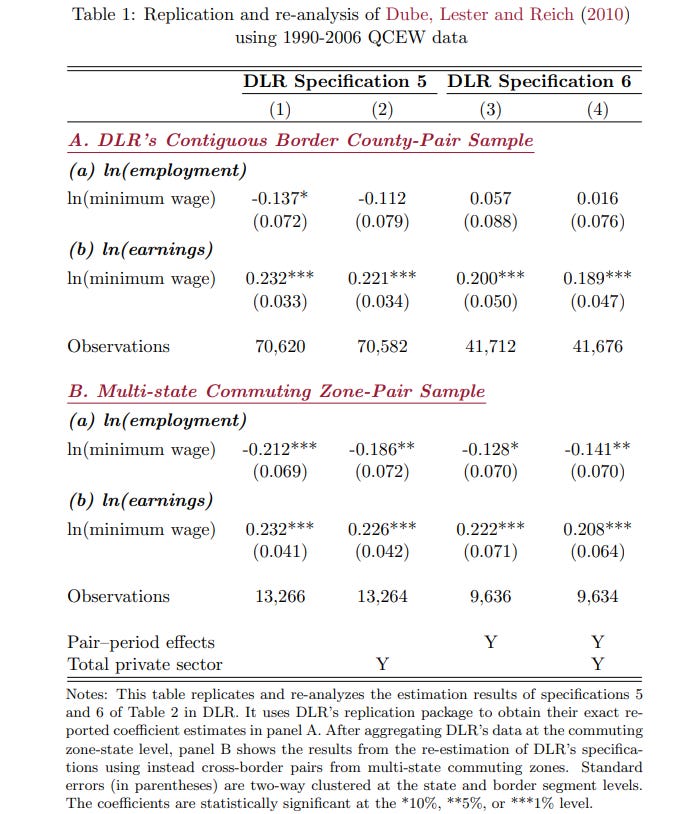

These results were questioned by Jha et al. (2024), who argued that the county-pair approach used by Dube et al. was sub optimal. Instead, they compared counties within the same commuting zones, that is, counties between which there are a lot of work commutes. Among their arguments in favor of this method, these researchers noted that two of the three authors of the original paper (i.e., Dube et al., 2010) had previously written that the commuting zone approach is superior. Their semi-replication is summarized in the following table (DLR = Dube et al.):

It can be seen that the employment effect reversed sign, became much larger, and obtained statistical significance. The elasticity was -0.68 with a p value of approximately 0.043. After this, Jha et al. went on to conduct their own analysis, which will be analyzed a little further down.

2.1a.13. 441 Minimum Wage Spikes Between 1985 and 2012

The next such study was Joan Monras’ (2019) study of all changes in state-level minimum wages between 1985 and 2012. Rather than using bordering county pairs as experimental and control groups, he used the low skilled and high skilled population of the same state. Because low skilled people are much more likely to be affected by the minimum wage, this should work, but it is probably inferior to the approach used by Dube et al. They report their results in terms of FTE workers, defining part time workers as half a full time worker.

The main table reported a decrease of 1.88% in the FTE employment rate of low skilled individuals (Table 3). This was statistically significant at a p value of about 0.035, which makes Monras’ study one of the only ones with statistically significant effects. Despite probably having a worse methodology than the similar one conducted by Dube et al., it is a much better in terms of statistical power.

2.1a.14. 138 Minimum Wage Spikes Between 1979 and 2016

Another such study was published in the same year by Cengiz et al. (2019), looking at 138 state-level changes in the minimum wage. The control group was jobs with wages that were slightly above the new minimum before it was implemented, while the experimental group was jobs with wages below the new minimum. Their DiD effect size was estimated by subtracting the change in the number of jobs which pay slightly below the new minimum from the change in the number of jobs which pay slightly above it. Put more simply, they did the following: 1) found the number of jobs paying below the new minimum that were lost after the new minimum was implemented; 2) figured out how many more jobs paying slightly above the new minimum there were after it was implemented than before; and 3) subtracted the first number from the second. If, after the increase, there were more sub-minimum jobs lost than sur-minimum jobs gained, the effect on employment is estimated to be negative. In their preferred model (Table 1, column 7), the effect on employment was positive, but insignificant, with an implied elasticity of +0.41.

2.1a.15. 7 Minimum Wage Spikes Between 2010 and 2018

This study, conducted by Dube (2019, technical appendix A), is almost exactly the same as the one that has just now been described, except with further controls. Between 2010 and 2018, seven states increased their minimum wage to some value above $10.50, while 21 states (plus New Mexico, which was excluded due to major increases in local minimum wages) maintained their minima at exactly the federal level during this period. His main table (A1) lists the elasticity estimates from various models—all are positive, but none are even close to significance. Because I genuinely cannot tell which specification is the best, I chose the second column due to its estimated elasticity being around the average of the other equally good models. The result in this column was an elasticity of +0.32, similar to the results from Cengiz et al.

2.1a.16. Minimum Wage Spikes Between 1990 and 2016

As mentioned in section 2.1a.12, Jha et al. (2024) also analyzed an original dataset. Their study consisted of changes in minimum wages both at the county and state level within commuting zones between 1990 and 2016. Their main results (Table 3, column 1) indicated a statistically significant decline in employment, and an elasticity of -1.29 (p= ~0.005).

2.1a17. Summary

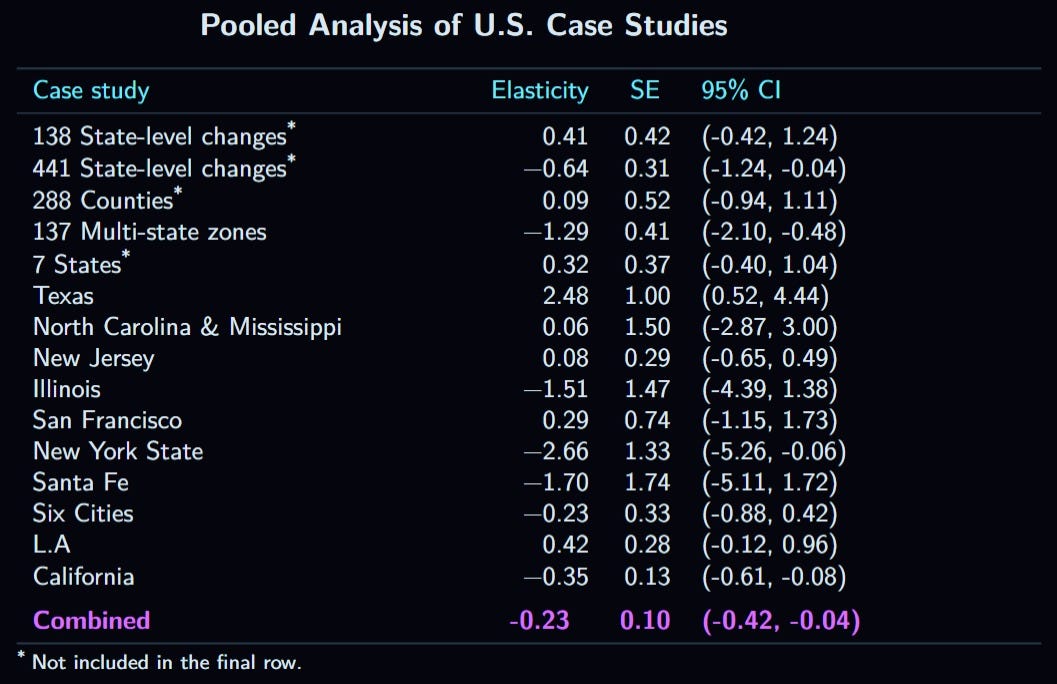

Despite these studies often being cited as definitive proof that raising the minimum wage has no impact on employment, there are several problems with using these studies to support that conclusion. The most obvious issue is that all of these studies were underpowered, and so cannot reliably estimate a moderately negative effect even if it assumed that the true effect is negative. In Card & Krueger’s (2000) final analysis of the 1992 New Jersey minimum wage found a DiD effect size of 0.272 for the increase when the control group was businesses from fourteen Pennsylvania counties, with a standard error of 1.029. Using the standard formula, this indicates that the 95% CI was -1.745 to 2.289. Below is a table depicting the elasticity estimates, their standard errors, and their 95% CIs. The overall elasticity estimate is presented in the bottom row, excluding several of the estimates that pertain to multiple events to avoid overlapping samples.11 The pooled elasticity is -0.27, with a p value below 0.005.12

Overall, then, the U.S. studies which used this method, while inconsistent, come up with a highly significant negative elasticity when pooled. The point-estimate, -0.27, is not outside the traditional estimate of -0.1 to -0.3, and includes that entire range in its confidence interval.

2.1b. The Case Study Method: Studies Outside the U.S.

Studies from outside of the U.S. used much weaker designs because changes occurred at the national level rather than the state or local level as in the American studies. Therefore, the treatment and control groups are usually not as well defined.

2.1b.1. Cost Rica, 1988-2000

Gindling & Terrell (2007) explored the effect of changes in the minimum wage in Costa Rica between 1988 and 2000, by comparing workers in the covered and uncovered sectors. their estimates indicated that a 10% change in the minimum wage would decrease employment by 1.09%, which effect was marginally significant (p<0.1). Average hours of those remaining in the workforce in the covered sector also dropped, and the estimated loss was statistically significant, but the coefficient was actually about the same in the uncovered sector (not significant), making the evidence in this regard difficult to interpret.

2.1b.2. The 1990-1994 West Java Wage Spikes

In 1990, the difference in minimum wages between two bordering regions in Indonesia, Jakarta and West Java, was approximately 36%. However, between 1990 and 1994, the West Javan minimum wage increased so much that it bridged the gap entirely. Alatas & Cameron (2003) used detailed data of comparable businesses in both regions between 1990 and 1996 to examine the effect that the minimum wage increases between 1990 and 1994 had on businesses in Botabek (located in West Java) relative to Jakarta. The best estimates revealed mostly negative effects, depending on the size of the business and what the comparison years are. Because the biggest increase in the minimum wage in Botabek relative to Jakarta occurred in 1991 (see Table A1), 1990 should probably be used as the baseline year. If that is done, the effects are negative for small domestic and large foreign businesses, but positive for large domestic businesses. Weighing the results by sample size and combining them, there is a statistically insignificant reduction of 23.34 workers per firm, equivalent to a decrease of 5.5%.13

2.1b.3. Western Australia, 1994-2001

Between 1994 and 2001, there were several minimum wage spikes in West Australia. In order to estimate the effects of these spikes, Andrew Leigh (2003) compared employment changes among West Australian workers after each spike to workers residing in the rest of Australia. When the effects of all of these increases were put together, the elasticity of employment relative to the minimum wage was estimated to be -0.13, meaning that a ten percent increase in the minimum wage would decrease employment by a 1.3%. This effect is highly statistically significant (p= ~0.0021). However, when disaggregated by age groups, only the coefficient for 15 to 24 year-olds remains significant at conventional levels (elasticity of -0.389; p<0.005). Because youths are typically the group examined for this type of analysis, though, this result is not very surprising.

2.1b.4. New Zealand, 2001

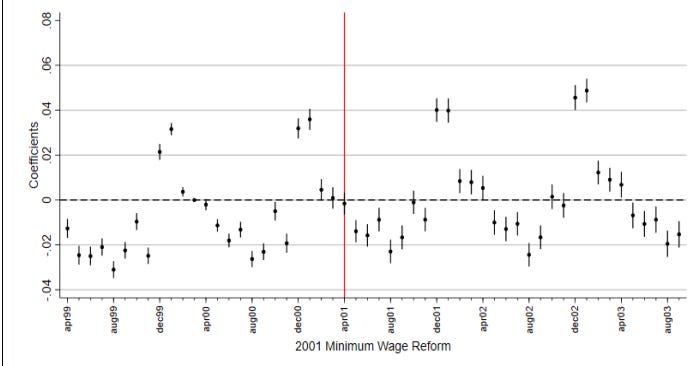

In 2001, New Zealand increased its minimum wage for teenage workers. Hyslop & Stillman (2007) explored the effects of this change by using a comparison group of workers aged slightly above the cutoff (i.e., 20 and older). In their most basic DiD estimates, where the effect size is equal to the employment change for 16-17 and 18-19 year-olds minus the change for 20-25 year-olds, the estimated change in employment is positive for both teenaged groups, though not close to significance for either. A more intricate analysis with controls was also provided. In the best model (Table 4, column 7), the DiD estimates were negative for both groups of teenagers, though none are statistically significant.

This analysis was replicated by van der Westhuize (2022) using the same methods but with better data. Using the simple DiD approach, he found, similarly to Hyslop & Stillman, a positive effect on both groups of teenagers, though, unlike the prior study, the effect was highly statistically significant. In the regression results, all of the estimates were still positive, but smaller in magnitude (Table 5, column 13); all were highly statistically significant. However, the author noted that tests of parallel trends—that is, tests to see if 20-25 year-olds and teenagers had similar employment patterns before—showed that, even before the change in the minimum wage, shifts in teenaged employment did not track shifts in young adult employment. This was shown in two figures, each including all of the controls used in the main regression model (i.e., Table 5, column 13). To avoid redundancy, I only show the trend analysis for the 16-17 year-old age group below. Clearly, the parallel trend assumption was violated, making DiD analyses untenable.14 The author concluded that, despite the strong looking regression results, “the true effects on employment remain uncertain” p. 26).

2.1b.5. New Zealand, 2008

Seven years later, New Zealand enacted another teenager-specific minimum wage increase, though, this time, only for 16-17 year-olds. Using the exact same method as before, Hyslop & Stillman (2021) found statistically insignificant negative results when using a basic DiD model, and tiny, insignificant coefficients with varying signs in the more complex regression model (Table 4, column 9). However, parallel trends were not tested for here, which may mean that the problem identified with the earlier analysis may apply here, too. A much bigger issue, however, is the fact that the estimated effect on weekly income is insignificant and/or negative in most of the year-specific coefficients (Table 7)! Clearly, not much, if any, weight should be placed on this study.

2.1b.6. The 2003-2012 Brazil Minimum Wage Spikes

Saltiel & Urzúa (2022) analyzed all changes in the minimum wage in five Brazilian states between 2003 and 2012, with the control group being a bordering state. Specifically, they examined the restaurant and accommodation industries. Their best model showed a slightly positive, but nowhere near significant, impact on employment (Table W2, column 8).

2.1b.7. The U.K., 2011-2019

In the United Kingdom, local councils are allowed to set living wages, which are above the minimum wage. Datta & Machin (2024) compared areas that had a higher minimum wage (i.e., a living wage ordinance) to those that only had the national minimum wage, using data from a large company with locations throughout the U.K. They found a positive, but only marginally significant, effect on entry level employment.

2.1b.8. Summary

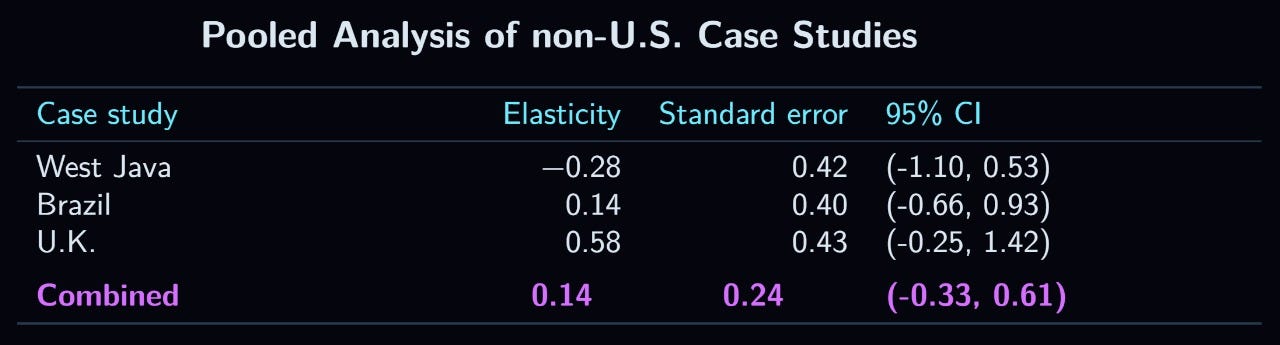

Below is a table summarizing the non-U.S. data, though, unfortunately, with only three estimates:15

While the point-estimate is positive, the confidence interval is so wide as to once again include the entire traditional range of -0.1 to -0.3. On its own, the non-U.S. data does not provide much evidence against the old consensus.

2.1c. The Case Study Method: Synthetic Control Studies

All of the studies reviewed in sections 2.1a and 2.1b used natural controls—either workers/businesses/jobs not affected by the minimum wage change, or nearby states that were not affected. Another approach is to use a synthetic control, in which data from many possible controls are put together, to create a hypothetical control that is very close to the treatment group before the minimum wage increase. In practice, this is usually done by taking a change in one state, and then combining data from all states which didn’t have a rise in their minimum wage, weighted such that the hypothetical control state you created most closely matches the treated state in terms of whichever variables you choose to include; states which are used to make the synthetic control are called donor units. The biggest issue with this method is that there is no way to account for unobservable characteristics, which is one of the main reasons that natural controls were promoted by the New Economics in the first place.

However, as critics of the New Economics have pointed out, there was never much reason in the first place to believe that bordering states are the best control group. For example, Neumark et al. (2014) wrote, “nothing in the Card and Krueger study establishes that Pennsylvania is a good—let alone the best—control for New Jersey” (p. 621). Indeed, in many comparisons, there was a sizeable difference between the treatment and control group in terms of its observed characteristics before the spike, and observable differences should surely be expected to matter more than unobservable ones when state-level economic statistics are so thorough. This was demonstrated in the same paper by Neumark et al. (Table 3), which found that the synthetic approach placed the vast majority of its weight on donor units outside of the same Census Division (i.e., only between a quarter and a third of the total weight was, on average, placed on states within the same region for a given variable, which is only about two to three times as large as chance, given that there are nine such divisions). The synthetic approach appears to be supported by researchers in the New Economics, and has been employed in several studies that used the case study approach.

2.1c.1 The 2005-2006 D.C Minimum Wage Spikes

As reviewed in section 2.1a.5, Sabia et al. (2012) explored the employment effect of the large New York minimum wage increase between 2004 and 2006, and found a statistically significant decline in employment. In the same paper, they also used a synthetic control with seven states acting as donor units. They found a larger employment decline with this approach than when they used a natural control, though the standard error was much higher, and the result was only marginally significant (p<0.1). However, calculating the elasticity was not possible, because change in the average wage was not calculated.

Fortunately, this study was soon criticized by Hoffman (2016), who tried to replicate it with a more complete version of the same dataset. He found a smaller effect on employment, and this effect was no longer significant. This led Sabia et al. (2016) to redo their synthetic analysis using the same dataset as Hoffman. They found that the states they used as controls were, based on their weights in the synthetic control, not very good. More importantly, their synthetic DiD estimate found approximately the same effect size on employment, at almost the same p value (~0.07 vs. ~0.046) as in the natural controls in the original analysis, though it is not possible to calculate the elasticity because they did not compute the effect on average wages.

In the same article, they also provide estimates for several other states as well as D.C,16 and, in those cases, do provide wage-change data. All of these had a large increase in their minimum wage between 2004 and 2006. Unfortunately, however, the increase in wages for 16-19 year-olds without a high school degree was only statistically significant in the case of D.C (all of the other states’ effect sizes were tiny, not just insignificant), so that is the only location that is possible to analyze. These changes, according to Google, occurred in 2005 and 2006, with increases to $6.60 and $7.00, respectively, from $6.15 at the start of the period. There was an estimated rise in employment of about 4.62%,17 which does not attain anything close to significance.

2.1c.2 Minimum Wage Spikes in Six Cities Between 2009 and 2015

Nadler et al. (2019) provide synthetic estimates for each city in the study previously analyzed in section 2.1a (Algretto et al., 2018). Unlike that study, which only reported the aggregated outcome, Nadler and his team report outcomes for each city separately. Of the six cities, four had a statistically significant increases in income; these were Oakland, San Francisco, San José, and Seattle. One city (Oakland) had a statistically significant positive effect on employment, while the other three had very small and insignificant effects.

The Seattle data has been analyzed in a more detailed way by Jardim et al. (2022). For their donor units, Jardim and his team used localities in Washington but outside King county (where Seattle is). Because there were two increases, one to $11 in 2015, and the other to $13 in 2016, their results can be used to calculate two different elasticities. The former elasticity estimate is -0.77, but nowhere near significant(p= ~ 0.43). The latter, on the other hand, is even more negative, at -1.95, and is now significant (p<0.01).18 Both elasticities are based on hours.

2.1c.3 The New York and California Minimum Wage Spikes Between 2013 and 2019

Wiltshire et al. (2024) used state level changes in the minimum wages of New York and California between 2013 and 2019, specifically looking at the 36 counties with the highest population. The synthetic control was based on 122 counties that stayed at the federal minimum wage during the entire period. Their main table’s best model shows a statistically insignificant decline in employment of 0.22%.

2.1c.4 28 State-level Minimum Wage Spikes Between 1979 and 2013

Dube & Zipperer (2015) used the synthetic control approach to measure the effect of 28 difference minimum wage increases between 1979 and 2013. None of the states’ employment changes were statistically significant using even an alpha of 0.1 (Table 5), and neither was the combined effect. The pooled elasticity was -0.16, with a 95% CI of (-0.54, 0.21).19

2.1c.5 The 2015 Germany Minimum Wage Spike

In the beginning of 2015, Germany raised its national minimum wage to €8.50 per hour. The effects of this minimum wage were assessed by Hakobyan (n.d), who created a synthetic control using data from eight OECD nations which had no minimum wage and were sufficiently developed. Because some industries were given about two years of leeway before the minimum wage became binding, employment effects were assessed as of the second quarter of 2017. Employment was measured as the employment rate of those aged 15 to 24. The finding was that the minimum wage reduced employment by 4.79 percent. Unfortunately, this study could not be included in the summary results because data regarding SE and change in average wages were not reported.

2.1c.6 The 2019 Spain Minimum Wage Spike

Roughly the same method was used by Arnadillo et al. (2024) to study the effects of the national minimum wage increase in Spain, which occurred in 2019. They found essentially no effect, but, again, these results could not be included in the summary statistics because they did not report change in wages or the standard error.

2.1c.7. Summary

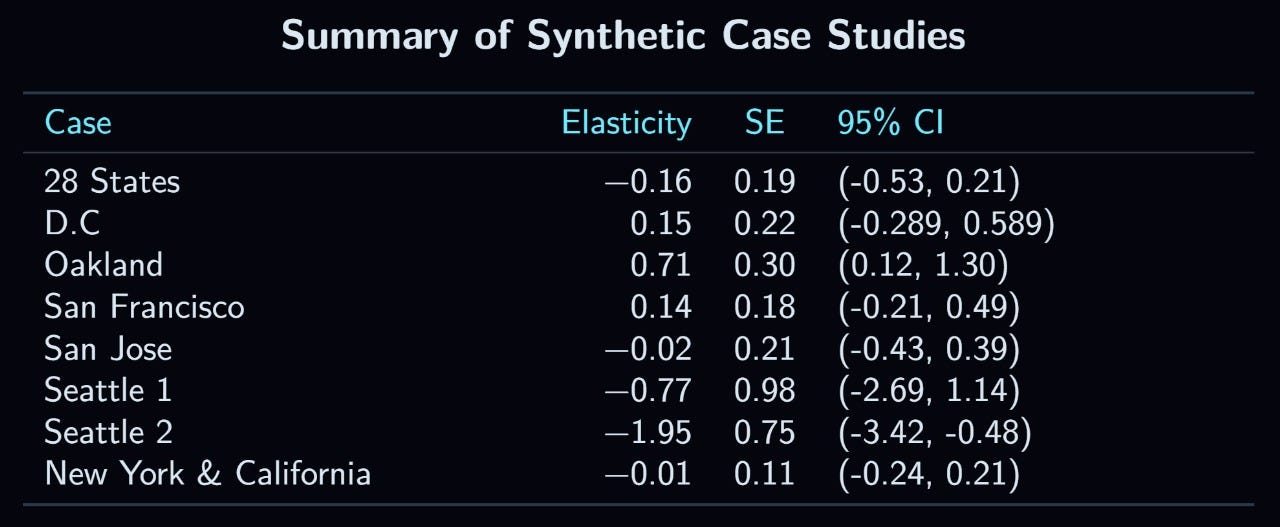

Unfortunately, I could only find four studies whose data could be included in the summary table, all of which come from the U.S., with a total of eight different estimates. Below is a table summarizing the results:20

Unfortunately, it was not possible to pool these studies, due to their standard errors not being comparable, as synthetic studies require permutation-inferred SEs and different studies handled this in different ways. The overall unweighted average was -0.16, while the median was -0.02, with the latter probably being a better summary statistic.

2.1d. The Case Study Method: Overall Summary

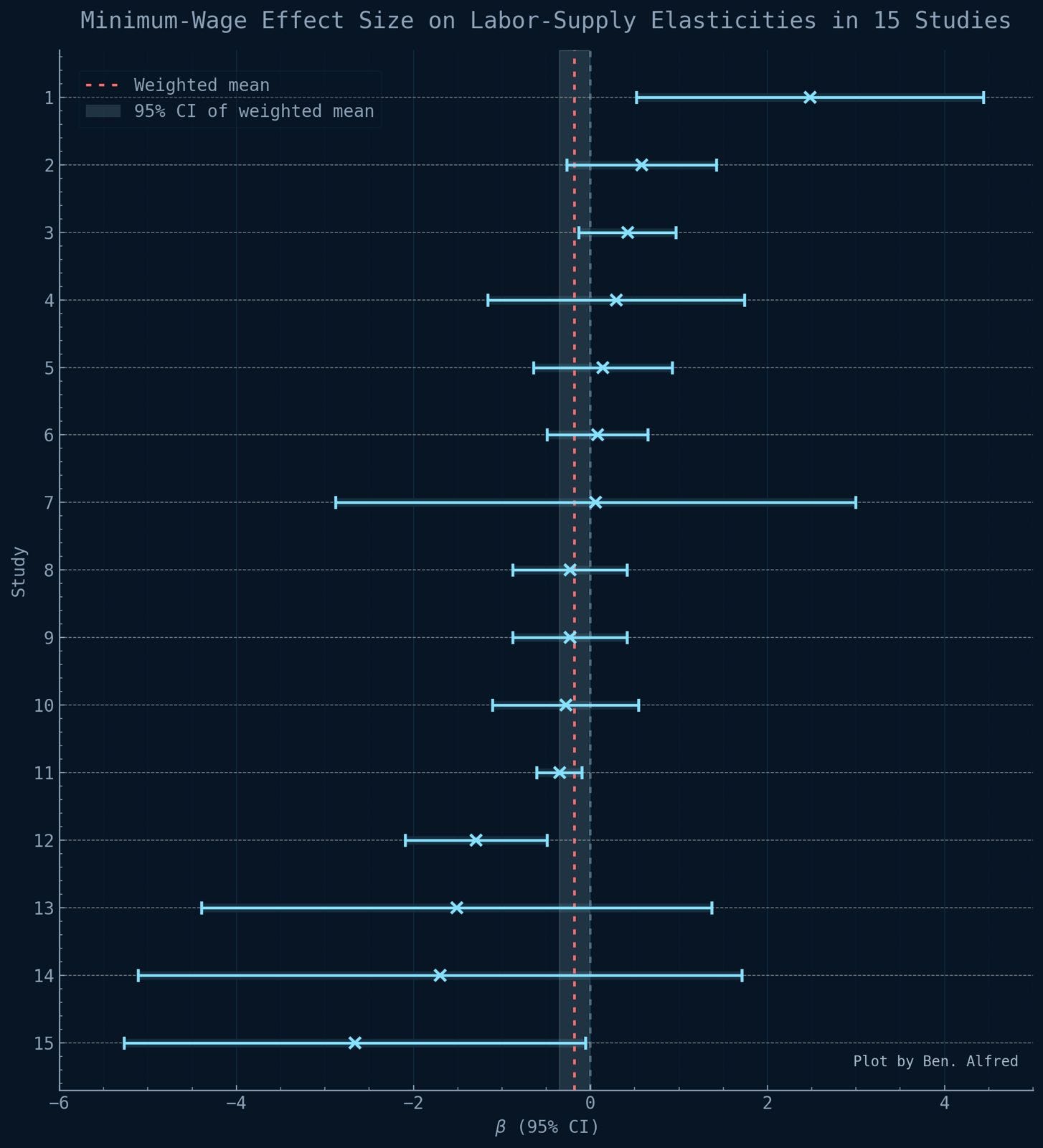

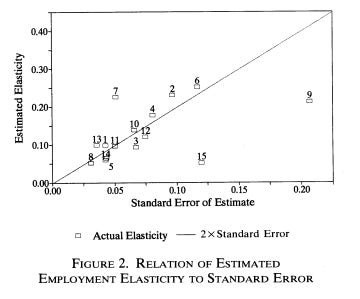

In all, case studies were remarkably inconsistent, because of their low precision. Combining all three sections—the U.S., non-U.S., and synthetic data—there were 32 estimates, of which 18 were positive, 13 were negative, and one was inconclusive. Of those studies finding significant results, however, the ratio is much less even: six negative and two positive. In order to get a better idea of the true effect, I combined all of the elasticity estimates, for a total of 15 elasticities with standard errors. A table summarizing each elasticity estimate would be too large to include here, the data is represented in the following chart instead:

The average elasticity, weighted for SE, which is colored red, was -0.18, with a 95% CI ranging from -0.36 to 0. The effect is just barely insignificant (p= ~0.0504). Unfortunately, the literature is simply too imprecise to give a useful point-estimate. When I estimated the power of each of the studies (including overlapping samples, but not including the synthetic control studies) to detect an elasticity of -0.2 (i.e., the probability that they would find a significant negative effect if the true effect were -0.20, based on their SEs), none met the typical threshold of 80%! The average power was just 13%, while the median was 12%. Clearly, the state of this literature is very poor, and it is not surprising that so many researchers in the New Economics have concluded that the effect is either positive or null.

2.2. The Differential Impact Method

In this method, the effect of a given minimum wage increase is estimated by comparing regions, or, in some cases, industries, which are differentially affected by the increase. The differential impact is estimated by the portion of workers with wages below the new minimum wage, or, in some cases, the ratio of the new minimum to the average wage in a location. The impact of the minimum wage is typically referred to as its “bite”, whichever way it is measured. For simplicity, I will only review national increases here, excluding a few county-level analyses of state-level increases in the U.S.

2.2.1. U.S., 1990

The first study to implement this methodology was published by David Card (1992b),21 and was based on the the 1990 federal increase from $3.35 to $3.80. According to him, the portion of teenager workers earning less than the new minimum before it went into effect ranged from “under 10% in New England and California to over 50% in many southern states” (p. 22). Therefore, there was considerable variation in bite. Card categorized states as either low-wage (and therefore high bite), medium-wage, or high-wage, and found that all categories of states experienced increases in hourly wages and drops in their teenage (16-19) employment rate between 1989 and the same quarter of 1990. Because the increase occurred in April, there were three post-treatment quarters. Card concluded that his analysis showed that the federal increase had no effect or, if anything, increased employment, as the overall employment loss was lower among low-wage states than high-wage states. However, using the same data, one could reach a different conclusion. By adjusting for the change between the first quarter of 1989 and 1990, during which data would reflect a pre-minimum wage growth trend, I got the following changes: -14.38% for low-wage states, -8.16% for medium-wage states, and -0.60% for the high-wage states.22 This is because the pre-treatment trend was already such that lower wage states were gaining employment much more quickly than the medium-wage states, while the high-wage states were losing it. These numbers should be interpreted with caution because the low-wage employment change (not the adjusted change, but the one presented by Card) was not statistically significant, and the other two categories’ changes have very wide confidence intervals.

Next, Card moved onto a much better analysis, where he examined state-level changes (including D.C) as a function of the fraction of teenagers affected by the minimum wage (the same criterion as he used to sort the states into wage categories). In the best specification, he found an insignificant elasticity of +0.19, though this again did not adjust for pre trends; though perhaps much of the pre-trend effect, if there was one, would have been accounted for by controlling for changes in overall employment, which Card did do, making such an adjustment unecessary.23

2.2.2. The 1967-68 U.S. Minimum Wage Spikes

In 1966, legislation was passed that increased the U.S. minimum wage by 28% in two phases—first in February, 1967 and again in February, 1968), and expanded its reachto millions of more workers, as part of Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty. Bailey et al. (2021) evaluated the effect that this change had on men aged 16 to 64.24 The bite was determined by the share of a state’s workers earning less than the second increase (i.e., the one in 1968) in 1966. In the U.S. as a whole, a little over 16% of workers were earning less than the new minimum, with state-level variation from slightly less than ten to a little over thirty percent. In the best model (Table 3, column 4), the elasticity was -0.28, but only marginally significant, for hours worked.

2.2.3. The 1996 and 1997 U.S. Minimum Wage Spikes

In 1996, the U.S. federal minimum wage was increased from $4.25 to $4.75, and, in 1997, to $5.15. Both changes were studied by Thompson (2009) who, rather than using states as his unit of analysis, used county-level data. High and low impact counties were defined by the mean teenage earnings. Three different estimation strategies were used: 1) comparing counties in the top fifth of the teen wage distribution to those in the bottom fifth; 2) contrasting those in the top third to the bottom third; and 3) using a continuous treatment. Probably, the last of these is the best measure of bite. The continuous measure serves as a form of inverse bite, as it regresses an additional $100 in mean teen quarterly wage on the impact of the spike. While the coefficient for this variable on employment was very small, it represented an elasticity of about -0.43 for the 1996 spike and -0.28 for the latter increase.25

2.2.4. The 2003-2012 Brazil Minimum Wage Spikes

Between 2003 and 2012, the Brazilian minimum wage grew by almost two thirds in real terms, according to Saltiel & Urzúa (2022), whose paper I already analyzed above in section 2.1b.6. Here, I focus on a different analysis by the same authors, which exploited the regional variation in bite from these increases, measured by the ratio between the median wage of a state and the new minimum wage. These researchers found a statistically insignificant decline in employment, which, unfortunately, cannot be converted to an elasticity because of a lack of wage data.

2.2.5. The 1981 France Minimum Wage Spike

In June of 1981, the French minimum wage increased by ten percent. In order to assess the impact of this change, Bazen & Skourias (1997) examined the shift in teenage employment between march and October of that same year, looking at 32 sectors, and measuring bite in terms of the portion of workers affected by the increase. In order to account for seasonal differences, a DiD approach was used, wherein the coefficient on the bite variable was adjusted by coefficient it would have had in 1980 (a form of pseudo event test). The effect was negative and large in magnitude, but nowhere near achieving statistical significance. The authors also examined the effects of further increases in the French minimum wage after 1981, but used the same bites for each sector, estimated based on the 1981 minimum wage, and so their results are difficult to interpret; I do not include the findings of this latter analysis in my summary.

2.2.6. The 2015 Germany Minimum Wage Spike

Bruttel (2019) has written a literature review summarizing evidence coming from Germany’s first ever implementation of a national wage. In terms of employment effects, he cited five studies that found a negative employment effect, one that found a positive effect, and another that found a negative effect only for youth employment, but a positive effect for the economy overall. All but one of these used a disparate impact approach, and, here, I will review those.

Ahlfeldt et al. (2018) found, using 401 county-units, and exploiting variation in bite, that a 1% increase in the minimum wage was associated with an increase of wages at the tenth percentile by half a percent, and employment by 0.06%, with an elasticity of 0.12. The increase in employment was statistically significant (p<0.05). On the other hand, Caliendo et al. (2018) estimated a large decline that was significant, using two different measures of bite, one based on the fraction of workers earning less than the new minimum, and the other based on the ratio of the minimum wage to the average wage (p<0.05 and <0.01). The main difference between this study and the last one is their inclusion of much better controls. An elasticity could not be estimated because of the lack of wage data.

Alfred Garloff (2017) used data from 141 labor regions, and found a significant decline in employment (Table 2, Panel B; p<0.05).26 However, many of the more specific models have insignificant or positive effects. Once again, there was no income estimate, so the elasticity could not be estimated. Holtemöller & Pohle (2017) used a few hundred state-industry units, but did not present their results in an easily interpretable manner, though they conclude that the effect was negative on “marginal” work (i.e., part time, low-wage labor) but positive on other forms of employment. There were no wage data.

Schmitz’s (2017) study provides more detail. Using data for 402 counties, he found a consistently negative effect of bite on employment which was statistically significant in three out of four of the regressions for “regular employment” and for all four for marginal employment. Bruttel (2019) reasonably summarized this paper as showing a decline of around 0.1% in regular employment and 1 to 1.4 percent in marginal employment. Once again, it was not possible to calculate elasticity. There were no other English-language publications included in Bruttel’s literature review.

Because the only study where it was possible to calculate the elasticity did not provide the standard error, there is no usable data for this minimum wage spike. However, it can be safely said that the best available evidence suggests a statistically significant negative effect (Caliendo et al., 2018).

2.2.7. The 2022 German Minimum Wage Spike

Several years later, Germany increased its minimum wage again. In a study published by Bossler et al. (2024), bite was defined as the fraction of workers in a given county that were below the new minimum wage before it was put into effect, and the unit of analysis was 400 counties. The effect on the overall employment rate was negative but small and insignificant (Table 2, column 2, November and December). Unfortunately, the income change using this exact method was not reported, but using an alternative method, described in a different part of the same paper, the change was calculated as about +5.7%. This gives an elasticity of -0.17, but, once again, it is not significant.

2.2.8. The 2001-2002 Hungary Minimum Wage Spikes

In 2001, Hungary raised its minimum wage by about 57%, and, in 2002, by another 25%. Harasztosi & Lindner (2022) examined the change in employment caused by these two spikes by comparing firms with different proportions of their employees earning beneath the 2002 minimum wage. The short term effects are measured using the coefficient for fraction affected for the changes from 2000 to 2002, while the medium term effects are estimated for the years 2000 to 2004. They find that the estimated decline for a firm whose employees were all earning below the 2002 minimum wage relative to ones whose employees were all earning above it was 7.6% in the short term, and 10% in the long term. Both of these were highly statistically significant (both p<5 × 10-14).

2.2.9. The 2004-2018 Poland Minimum Wage Spikes

In Poland, there is no local variation in the minimum wage, and the national minimum wage is set each year. These changes have been analyzed using bite variation between localities by two different teams of researchers—Majchrowska & Strawinski (2021) for 2006 through 2018, and Albinowski & Lewandowski (2022) for 2004 through 2018.

The first team of researchers defined bite as the ratio of the mean wage of a labor market (of which there were 380) and the national minimum wage. They found a negative relationship between employment growth and bite, indicating that the minimum wage reduced employment, though the effect was not close to significance in any model. The authors found that the estimated bite coefficients varied by year, but none of the by-year differences were statistically significant. Elasticity could not be calculated because of the lack of information regarding wages. The second team used 73 subregions, and calculated bite in the same way as the previous analysis. They found that bite actually had no relationship with wage growth rate in the full sample of regions, indicating that the minimum wage did not raise wages at all—which obviously cannot be true. When analyzing the effect in regions with mean wages in the bottom third of the sample, there was a statistically significant increase in wages and decline in employment, which implied an elasticity around -0.38 (p. 12). However, I do not feel comfortable relying on this study due to the weird full-sample results.

2.2.10. The 2003 South Africa Minimum Wage Spike

In March of 2003, the South African minimum wage increased, but only for certain industries. One of these industries was farm labor. Bhorat et al. (2014) exploited the fact that some industries were not affected by this change to estimate its effect. Their treatment group was unskilled farm labor, which was covered by the increase, and their control group was described as “unskilled, nonunionised individuals of working age, who are not covered by another sectoral minimum wage” (p. 3). They then calculated the DiD effect size for wages and employment by comparing these two groups before and after the change, controlling for district, and using the minimum wage to average wage ratio as the bite measure. Their results suggested that farm worker wages rose relative to the other unskilled workers’ wages by 25.11% (Table 5).27 The change in employment, measured in terms of the proportion of workers in the sample who are employed as farm laborers, is -5.47% (Table 4).

2.2.11. The 1988 South Korean Minimum Wage Spike

The first national South Korean minimum wage went into effect in the beginning of 1988, applying to all factories employing ten or more workers. Baek & Park (2016) studied the effect that this increase had on employment at these factories, using plant-level bite, defined as the difference between the pre-implementation mean wage at that factory and the new minimum. The effect size was positive but nowhere near significance.

2.2.12. Spain, 1967-1994

Dolado et al. (1996) examined changes in the Spanish minimum wage between 1967 and 1994, using the ratio between the average wage and the minimum wage for each region as the independent variable. These authors found a statistically significant positive relationship between the bite index and employment change over the whole age distribution (p<0.00002). When limited to just teenagers (16-19), the coefficient became negative, though only marginally significant, despite having twice the magnitude of the significant effect on overall employment (p<0.1). Furthermore, the same researchers examined in detail a 1990 change in the law, which made it so that the 17 year-old minimum wage also applied to children aged sixteen and younger, and also slightly raised the minimum for 17 year-olds. This resulted in a large increase in their minimum. Based on interregional variation, the bite index (now the fraction paid below the new minimum) had a negative coefficient for those aged 16-19 (unfortunately, sixteen year-olds could not be separated from those aged 17 and older), but was positive for those slightly older (20-24). The point-estimates for both seem somewhat high in magnitude, though standard errors were not given. In my opinion, the best conclusion from this paper is that the minimum wage reduces teenagers’ employment, but probably has a positive effect on older age groups’ employment.

2.2.13. The 2008-2013 South Korea Minimum Wage Spikes

South Korea increased its minimum wage each year from 2008 to 2013. Lee & Park (2025) analyzed the effects of these increases by using firm level data and a bite variable equivalent to the fraction earning at or above the old minima but below the new minima in each successive year. The effect on employment was negative but insignificant.

2.2.14. The 2016 U.K. Minimum Wage Spike

In 2016, the United Kingdom spiked its minimum wage to £7.20, and afterward increased it regularly. The effect of these increases through 2019 were studied by Giupponi et al. (2024), who measured bite in terms of regional differences in average earnings. Change in employment was estimated in the same way as in a study reviewed previously in section 2.1a.14 (Cengiz et al., 2019), and, because only those aged 25 and older were affected by the increase, only their employment was measured. Giupponi et al.’ main specification found an insignificant elasticity of -0.20, with essentially the same results for alternative regressions.

2.2.15. Summary

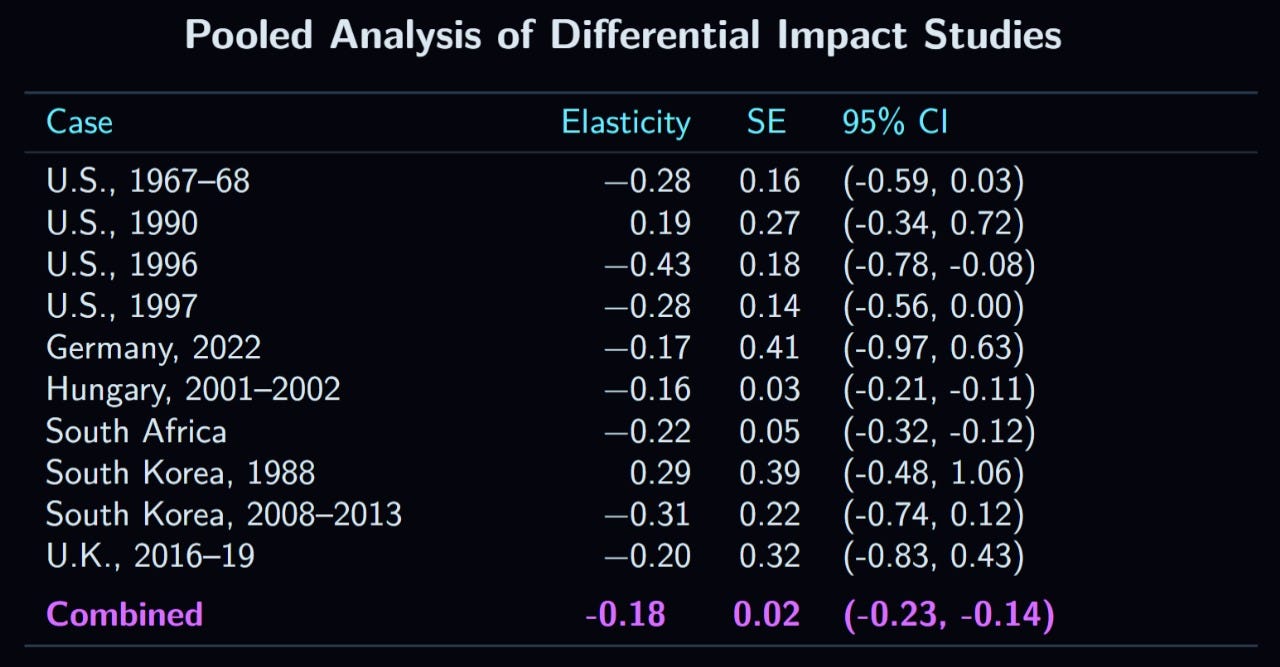

With a total of 10 elasticity estimates, the conclusion is largely the same as for the case studies:28

The pooled effect size is -0.18, with a p value below 1 × 10-13. Clearly, this method also gives results consistent with the traditional estimate.

2.3. The Longitudinal Method

The final method that I analyze in section 2 is the longitudinal method. In these studies, two groups of individuals are assessed in multiple waves—one control group and one treatment group—and their employment trajectories are compared. The initial wave occurs before the minimum wage increase, and the follow up occurs after an increase. The longitudinal method is intuitive because it directly compares individuals instead of cross sections of individuals or municipalities, and has been used in many studies of the minimum wage’s effect on employment, though not in as many as the case study approach.

2.3.1. U.S., 1975 & 1980-1981

This section reviews the two studies cited in Card & Krueger’s overview of this method (1995, pp. 223-231). The first was an analysis of the 1975 minimum wage increase to $2.10 from $1.60, conducted by Ashenfelter & Card (1981), and published as a discussion paper in 1981, but I cannot find this paper anywhere (hence why it is not linked in the in-text citation, though it is included in the reference list). On David Card’s website, it is listed as one of a few “Moldy Oldies” with no link, and, on his online resume, it is listed as unpublished. Therefore, I am here reliant on the summary given by Card & Kruger, which, thankfully, was thorough. The study’s methodology was simple: because the 1975 minimum wage increase did not apply to all sectors of the economy, the researchers compared employment trajectories for a treatment group of those earning less than the new minimum wage (i.e., less than $2.10) in affected sectors to a control group of those earning less than that amount in unaffected sectors. Specifically, the outcome measure was the probability that the same worker was still employed after the change. The dataset used to assess this was the National Longitudinal Study of Young women, so only outcomes for women aged approximately twenty to thirty could be assessed.29 Of those women earning less than $2.10 as of 1973 in the covered sector, 68.9% were still employed in 1975, compared to 67.8% of those in the uncovered sector. To further add onto the comparison, data regarding those earning more than $2.10 is also presented, also showing slightly lower attrition rates for the covered sector; a basic DiDiD analysis would show a decrease in employment of 0.8 percentage points that is nowhere near being statistically significant.30

The second study was conducted by Currie & Fallick (1996)31 using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth in order to study the 1980 and 1981 U.S. minimum wage spikes—the first bringing the minimum wage up from $2.90 to $3.10, and the latter to $3.35. The participants in this sample were, by the early 1980s, in their mid teens to early twenties. The treatment group consisted of people meeting the following criteria: 1) earning between the old minimum and the new minimum, and 2) working outside of the public sector, agriculture, and domestic service. The control group was made up of everyone who was employed before the minimum wage increases but was not included in the treatment group. Therefore, the comparison group included those earning below the old minimum and in the public, agricultural, and domestic service sectors, as these were presumably not affected by the minimum wage. The average wage gap for the treated group—that is, the difference between their wage and the new minimum—was 15 cents for the first increase and 18 cents for the second.

In their best model, the wage gap variable had a coefficient of -0.172 (Table 2, column 5), meaning that the each cent that a member of the treatment group earned below the new minimum decreased his chance of employment after the increase by 0.17% relative to the control group, which effect was highly significant (p<0.00002). Multiplying this by 15 cents gives an average decrease of 2.58%for 1980, and, by 18 cents, a decrease of 3.10% for 1981. Unfortunately, this variable’s coefficient was only estimated for the two effects combined, and so it is not possible to more directly separate the effects of the two increases. In the combined sample, the average wage gap was 17 cents, which gives a decrease of 2.92 percentage points. Using alternative measures in which the control group was limited in some way to be more comparable to the treatment group in terms of wages, Currie & Fallick got results that were either roughly equivalent or more negative.32

2.3.2. U.S., 2007-2009

In 2007, 2008, and 2009, the U.S. federal minimum wage increased from $5.15 to $5.85, then to $6.55, and, finally, to $7.25. Clemens & Wither (2019) analyzed the effect of these spikes by comparing individual-level employment trajectories of people residing in states whose minimum wages were increased by the federal increase (that is, whose state minima were below the new federal minima) to those residing in states which were not affected. Furthermore, they analyzed differences within states, too, by calculating the change in employment for those earning below the new minima to those earning above them, thus allowing a DiDiD estimate. The controls used in this study are mostly traditional, with the exception of a variable representing the severity of the housing crisis in a given state, as the period during which the effect was studied included the great recession. Clemens & Wither presented two estimates: one for the period of August 2009 to July 2010, and the other from the latter date into 2012. Their finding for the first period was an insignificantly negative effect on employment, and, for the second period, a highly significant negative effect (p= ~0.002).

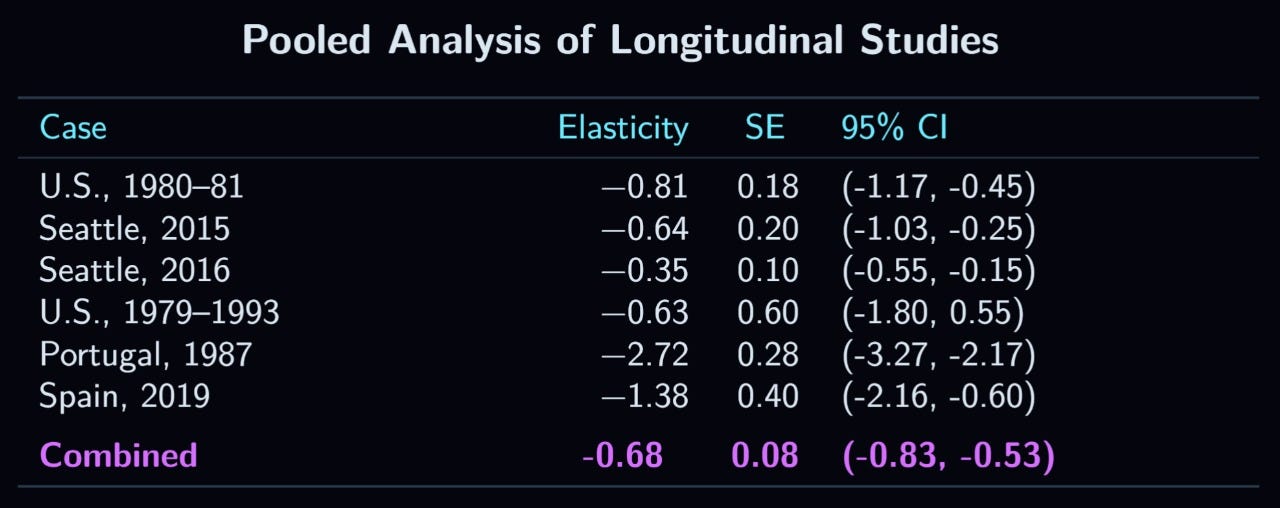

2.3.3. Seattle, 2015-2016

In April of 2015, Seattle’s minimum wage increased to an hourly rate of $11, and, in January 2016, it increased again to $13.33 Jardim alongside several other researchers (2022) used administrative data to study the effects of these increases, using workers in the state of Washington, but outside Seattle, as a control. For the first spike, their individual-level data showed an unweighted mean elasticity of -0.64 (p<0.005),34 and, for the second, -0.35 (p<0.0005), though it should be noted that the wage data used as a denominator came from their synthetic control analysis described in section 2.1c.3 , which is a possible limitation.

2.3.4. U.S., 1979-1992

Neumark & Wascher (1995) used individual level data from the entirety of the U.S. between 1979 and 1992. In two different tables, they compare the employment trajectories of teenagers (16-19) who had been earning a wage lower than the new minimum, the treatment group, to those who had been earning a wage at or above the new minimum. The first analysis, which is more crude, shows an insignificant decline in employment for the treatment relative to the comparison group, while the second analysis, which is probably superior, indicates an insignificant positive effect.35

2.3.5. The 1979 to 1993 U.S. Minimum Wage Spikes

Using essentially the same data as Neumark & Wascher (1995), but a methodology more similar to Currie & Fallick (1996), with the biggest difference being that the outcome variable is hours worked rather than simply employment, Zavodny (2000) examined the effects of minimum wage changes between 1979 and 1993. In her primary DiD analysis, the change in hours worked was actually positive, though not statistically significant. To explore this further, Zavodny used a subsection of “artificially affected” workers, who resembled the treatment group in terms of their wages, but who were not affected directly by the increase. This allows a DiDiD estimate, which corresponds to an insignificant loss of 0.48 work hours a week.36

2.3.6. The 1997-2010 U.S. Minimum Wage Spikes

A National longitudinal Survey more recent than the two analyzed in the studies examined in section 2.3.1 allows analysis of more recent minimum wage spikes on teenagers and young adults. Here, I am referring to the1997 version of the National Longitudinal Study of Youth. Beauchamp & Chan (2014) evaluated, using this dataset, employment changes caused by federal and state minimum wage spikes using the same method as Currie & Fallick (1996), with the only difference being that they used a dummy variable for whether or not a worker was in the treatment group rather than a continuous wage gap variable. Their results were ambiguous: split into several age groups, most coefficients were negative, and only the effect on the oldest group (25-30) was consistently significant. In the best model (Table 4, column 7), where the employment measure is the number of weeks one was employed in the last year, the effect on 20-24 and 25-30 year-olds was significantly negative (p<0.01 and p<1 × 10-9, respectively). It should be kept in mind that these results are not necessarily counterintuitive as, assuming that the coding was successful, everyone in the treatment group, irrespective of age category, should be affected by the minimum wage spike. The result for the 14-16 age group was positive, but nowhere near attaining significance. On the other hand, the results for ages 17-19 were considerably negative, though with its 95% CI’s lower bound being of a lower magnitude than the estimate for 20-24 year-olds. Overall, the best way to describe these results is that they are negative with ambiguous significance.

2.3.7. The 1998-2016 U.S. Minimum Wage Spikes

Using a very similar methodology to the one used by Beauchamp & Chan (2014), and also the same dataset, Fone et al. (2023) updated the prior results up to the year 2016. The employment outcome was measured in terms of the change in average weekly hours, and the sample consisted of participants aged 16 to 36 The overall effect size was a highly statistically significant decrease of 247.76 annual work hours.37

2.3.8. The 1988-1990 Canada Provincial Minimum Wage Spikes

Between 1988 and 1990, there were nineteen province-level minimum wage changes in Canada. Yuen (2003) examined the effects of these changes on employment by using two different control groups—those residing in provinces that did not increase their minimum wages during the period, as well as those with wages below either the old or new minima—and a treatment group of workers earning between the old and new minima prior to each increase. Their main table showed a highly statistically significant decline for both teens (16-19) and young adults (20-24), with p values below 0.005 and 0.001, respectively. The point-estimates imply that the employment of teenagers bound by the new minima decreased, on average, by 6.3%, while the same figure was 10.3% for young adults (Table 4, Fixed Effects). However, this estimate is potentially biased by the fact that both comparison groups are inadequate: the wage-related one includes workers earning much higher wages, rather than just those earning slightly higher wages, while the spatial control group suffers the same issue, as it is not restricted to only those in the same wage range. Furthermore, there is no DiDiD analysis, but, rather, both control groups are combined into one.

To rectify these issues, Yuen provided an additional analysis in which the control group consisted entirely of workers who, before a given increase, had resided in an unaffected province and had a wage in the same range as the treated workers (i.e., at or above the old minimum, but below the new minimum). The results (Tables 6A and 6B, Fixed Effects) indicate a 9.7% decrease in employment in the treatment group relative to the control for teenagers, and an 11.2% decrease for young adults. The effects were highly statistically significant (both p<0.005).38

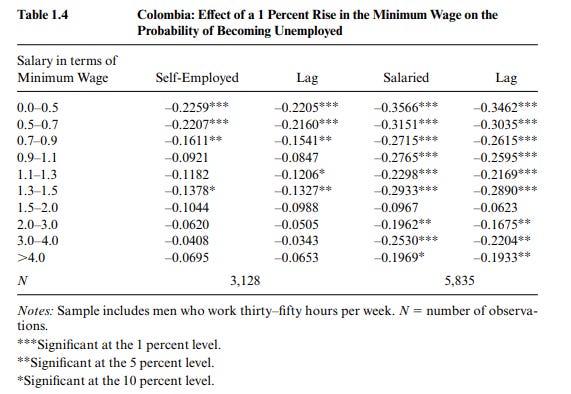

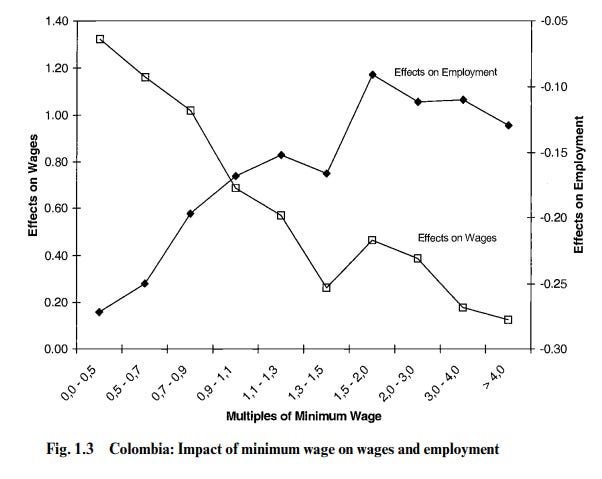

2.3.9. Colombia, 1998

Using a sample of men employed full time in 1997, and a follow up of the same men in 1999, Maloney & Mendez (2004) estimated the effect of the Colombian minimum wage spike in 1998. Their model used the self-employed, who were not affected by the minimum wage, as the control, and the rest of the men as the treated group. Maloney & Mendez concluded that the effect was negative, though they do not estimate the DiD significance. An examination of their main table shows that it is also possible to conduct a DiDiD analysis by comparing those below the new minimum in the original wave to those who were already above it. Weighted by the sample size (reported in Table 1.2 for the first wave, but not disaggregated by employment type), the DiD effect for those earning below 90% of the minimum wage (i.e., the first three rows) was -0.1114, while, for those earning between 10% more and twice as much, the effect was -0.0763, which computes to a DiDiD estimate of a loss of 3.5%. While large in practical terms, it likely would not be significant (unfortunately, this is impossible to calculate), and is also not robust to different specifications (for example, if the wage-group control were changed to those earning between 10% and 50% more, the DiDiD effect size would be a gain of 1.46%).