The history of the world has been through migrations, and for better or worse, displacements. Whether through conquest or settlement, humans have always intended to support what is naturally the most familiar thing to them. Saying such a thing in the modern day would get you discredited despite it being an obvious reality to folks 70 years ago. We have been spoon-fed a narrative that everyone who comes over to the first world is just simply searching for a better life and means to do no harm, and even if that were the case, it doesn’t explain why their concerns take priority over that of the native population. Modern immigration is a mess to put it lightly, and despite this, politicians will tell you constantly about how wonderful it is. Former President George W. Bush, for example, published a book titled Out of Many, One: Portraits of America’s Immigrants which paints a rosy picture of immigrants and depicts them as a great source of strength contributing to American prosperity. His successor Barack Obama echoed this sentiment, calling America “a nation of immigrants” back in 2016. Mainstream conservative outlets too, when arguing against illegal immigration, will not challenge this dogma, if PragerU’s video titled, you guessed it, “A Nation of Immigrants”, doesn’t speak for itself. The media loves this narrative too, as the New York Times has written articles like “Actually, the Numbers Show That We Need More Immigration, Not Less”, “How Immigrants Are Saving the Economy”, or “Why Rural America Needs Immigrants”, the Washington Post has written articles like “Earth to politicians: The U.S. has too few immigrants — not too many” or “Undocumented immigrants, essential to the U.S. economy, deserve federal help too”, and Vox has articles like “Immigration makes America great”, etc. It doesn’t just end with the media either, as organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union have an entire section dedicated to “Immigrants’ Rights”, think tanks such as the Brookings Institute or the Cato Institute make it clear their support for immigration, and the International Monetary Fund has an article titled “Migration to Advanced Economies Can Raise Growth”. So, the pro-immigration bias is pretty obvious everywhere. Well, this article seeks to counter this narrative and demonstrate that immigration is mostly a net negative.

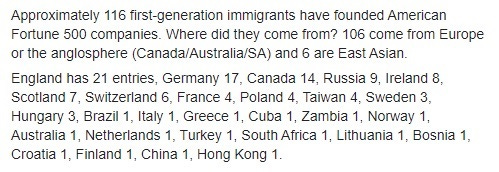

I will mainly be focusing on the United States, as it is the country that I am the most familiar with. There have already been excellent analyses done on immigrants in Europe, so it’s redundant for me to focus on them. Moreover, immigration is a much more pressing issue in the United States than it is in Europe and so requires more urgency, though obviously this is not to downplay the ongoing situation in Europe. One argument which is sometimes used in an attempt to preemptively shut down any discussion on this topic with regards to the United States is that the United States being the richest and most powerful country in the entire world is a tribute to the wonderful prosperity that immigration brings. This is of course a naïve argument. The United States was a great country because it was historically one of predominantly Northwestern European stock. Immigrants are not a homogenous group, there is no reason to think that a Norwegian migrant would have the same effect as a Somali, this is a very basic mistake many people make when discussing this issue. So, when I talk about immigration to the United States, I’m talking about the rather recent trend of third world migration that has become pronounced ever since the passing of the 1965 Hart-Celler Act and worsened by the Immigration Act of 1990. Conceptually, treating migrants as causal for American success is making the simple mistake of treating correlation as causation. Morley (2006) used time series analysis from 1930-2002 and performed a Granger causality test on immigration and economic growth and found that economic growth granger-causes increased immigration but failed to find evidence for the reverse. So, let’s just first try to be open to the ideas of those who have been challenging the pro-immigration narratives for decades and accept that the evidence is far from being as clear-cut as the media would like you to believe. With that, let’s get started.

CONTENTS

Against Immigration

Bad Arguments for Immigration

Against Immigration

Wages and Worker Displacement

To start, one of the most frequently debated impacts of immigration is on wages. Well, a 1998 report from the Center for Immigration Studies includes several findings on this, which are listed below:

Looking at all natives in the work force, the results indicate that a one percent increase in the immigrant composition of an individual’s occupation reduces the weekly wages of natives in the same occupation by about .5 percent. Since roughly 10 percent of the labor force is composed of immigrants, these findings suggest that immigration may reduce the wages of the average native-born worker by perhaps 5 percent.

In low-skilled occupations the effects of immigration are much stronger. For the 23 percent of natives employed in these occupations (about 25 million workers), a one percent increase in the immigrant composition of their occupation reduces wages by .8 percent. Since these occupations are 15 percent immigrant, this suggests that immigration may reduce the wages of the average native in a low-skilled occupation by perhaps 12 percent, or $1,915 a year.

The effect of immigration on the wages of natives is national in scope, and is not simply confined to cities or states with large concentrations of immigrants.

The findings indicate that immigration is likely to have contributed significantly to the decline in wages for workers with only a high school degree or less in the last two decades.

The presence of immigrants does not appear to have a discernible negative effect on the wages of natives employed in high-skilled occupations and may even increase wages in these occupations.

Native-born blacks and Hispanics are 67 percent and 37 percent, respectively, more likely to be employed in lowskilled occupation than are native-born whites. Therefore, a much higher percentage of minorities are negatively affected by immigration.

Because native-born blacks and Hispanics in the negatively affected occupations earn on average 15 and 14 percent less than whites, the wage loss resulting from immigration is likely to represent a more significant reduction in material prosperity for these groups.

Immigrants are 60 percent more likely to be employed in lowskilled occupations than native-born workers. Therefore, like native-born minorities, a larger percentage of immigrant workers are negatively affected by competition with their fellow immigrants.

An important thing to note here is that the notoriously pro-open borders Cato Institute loves to cite an economist by the name of Giovanni Peri, who frequently uses the ‘shift-share instruments’ measurement technique to capture the effects of immigration on native wages, often finding the effects to be either small or nonexistent. As Jaeger et al. (2018) explained, however, shift-share instruments almost always underestimates the true effect immigration has because it actually captures not only the effect the newly arriving migrants have, but also the recovery from previous waves of immigration. Peri has earned himself a place on the wall of shame for having 12 of his papers listed by the authors as examples of previous studies that used this flawed approach and underestimated the impact immigration had on native prospects.

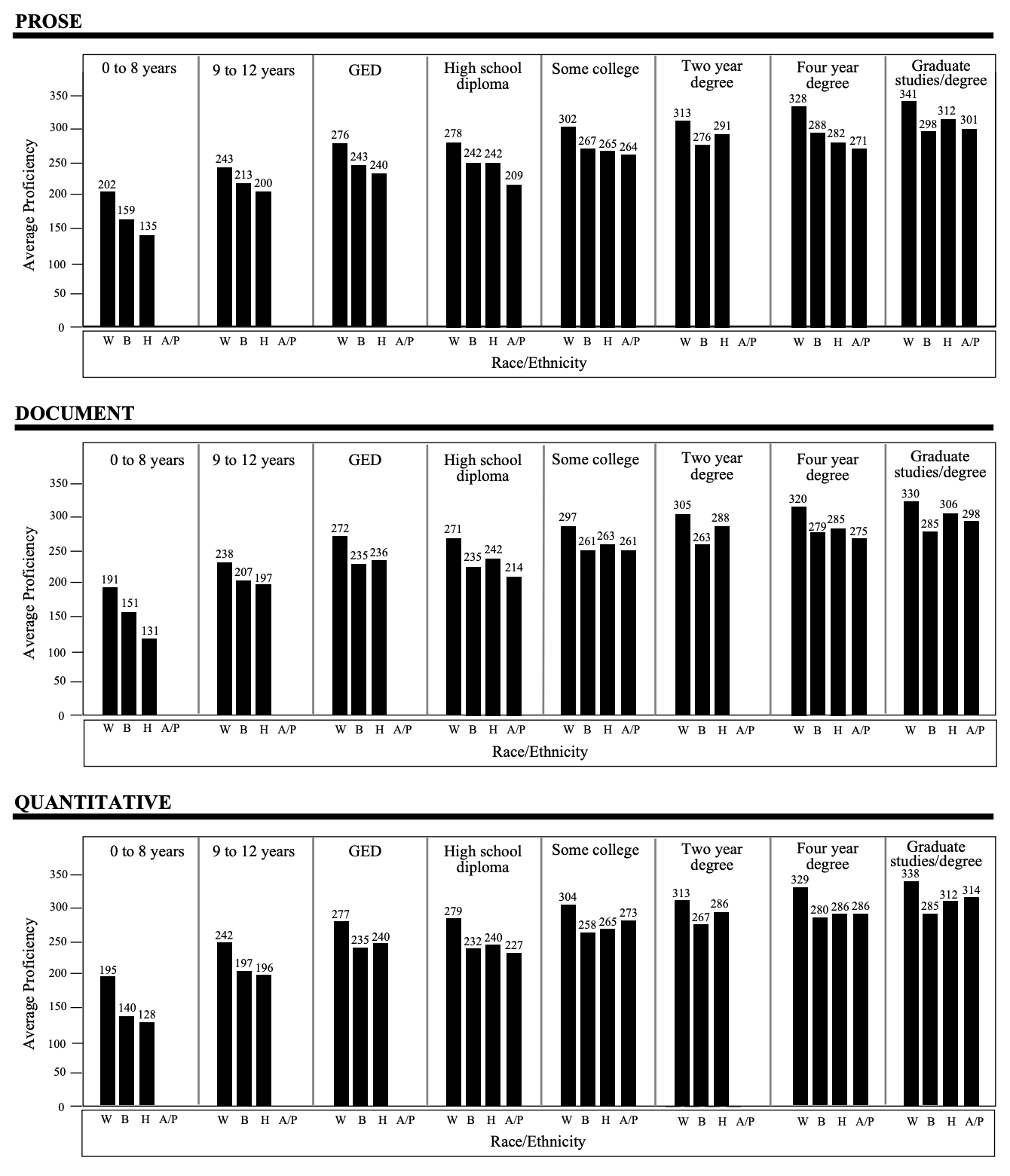

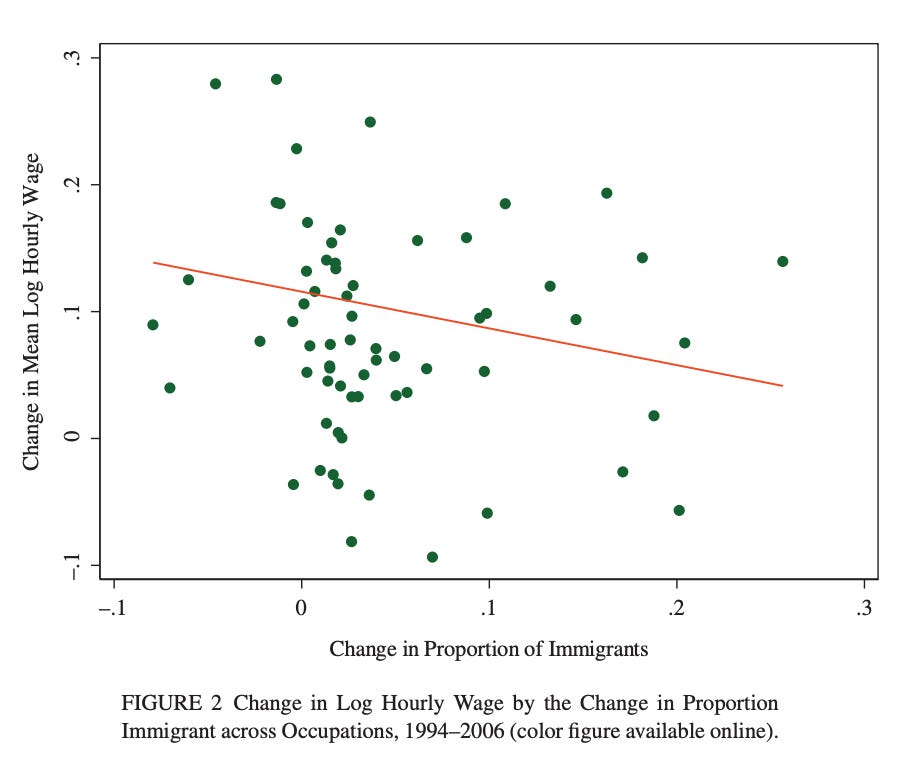

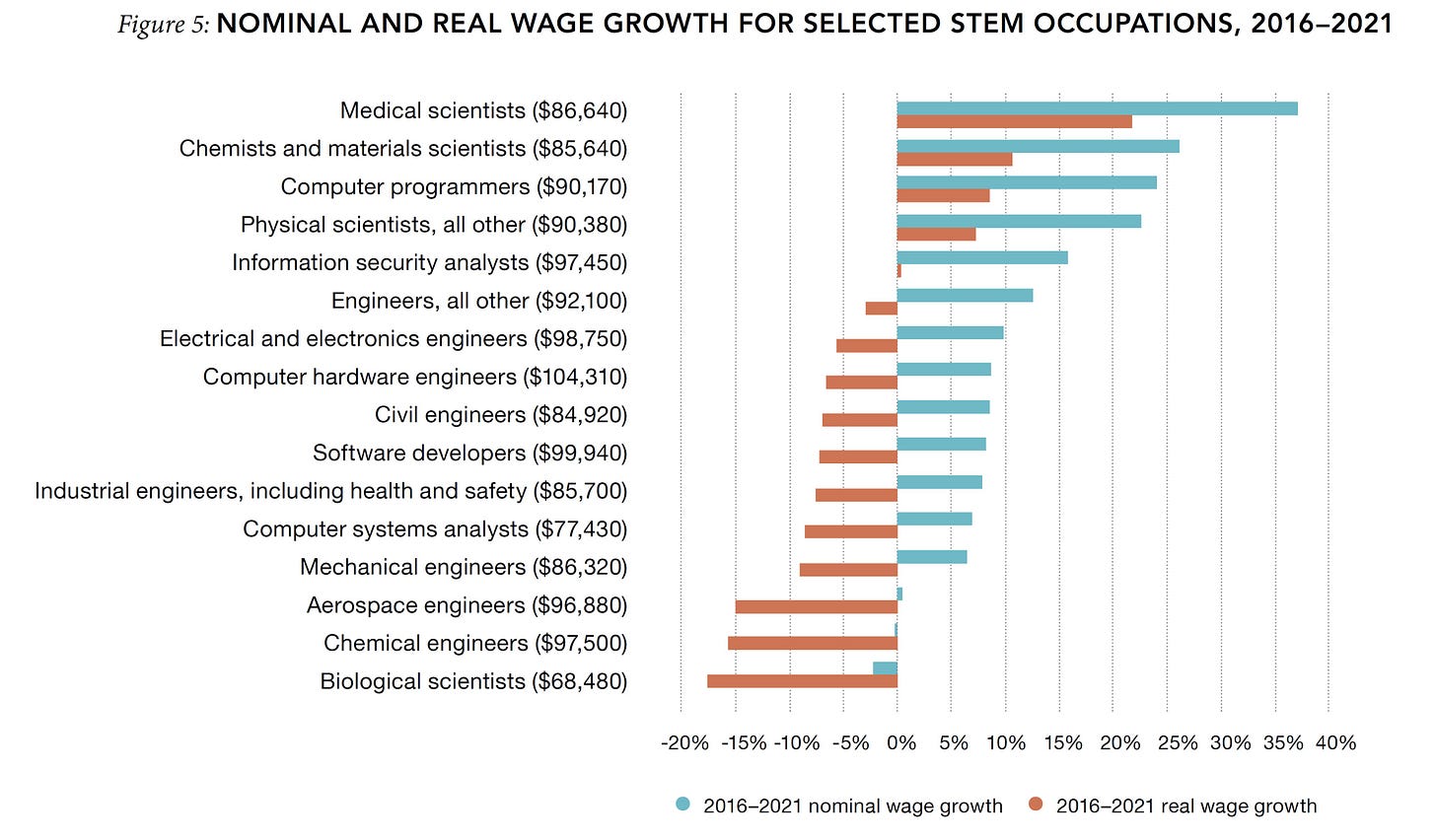

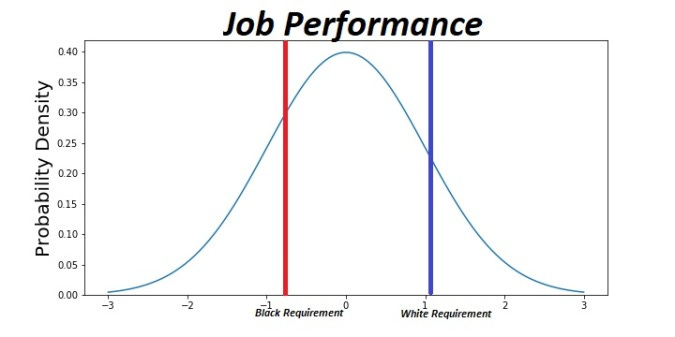

That aside, it’s true that the topic of the impact of immigration on wages is heavily disputed, and it’s likely that some pro-immigration advocates will attempt to cite studies showing a positive relationship between immigration and wages. These studies however, just as in the case of Giovanni Peri’s works, often rely on poor methodologies. One particular issue is that of heterogeneity, or that the effect of immigration on native prospects might not be all the same for different subgroups of natives. For instance, one paper found that the positive relationship between immigration and native wages at the local level only exists because of two things: natives whose prospects were hurt by migrants move out, and selective native in-migration. Controlling for this, the positive relationship disappears and workers that originally resided in these labor markets did not see gains to their income (Price et al., 2023). The authors also found that the natives that moved out suffered a persistent income loss, suggesting that the wage effects of migrants on natives are not always merely short-lived (Figure 5). To add on to that, Kim & Sakamoto (2013) has critiqued the spatial approach of measuring the relationship between immigrants and native wages. The spatial approach is extremely flawed because it doesn’t take into account the fact that immigrants don’t just move to anywhere for jobs, they will make decisions on where to move to based on the economic opportunities of local areas, or, to put it more simply, immigrants don’t pick random areas to move to, they pick nice areas, which is why this approach tends not to find significantly negative effects of immigration on wages. So here you can see that using the spatial approach, you’d end up getting a positive correlation between the number of immigrants and wages:

However, if we use the occupational approach, then this positive correlation disappears:

Lastly, from the same paper, here are the results using the occupational approach, which are clearly negative, at least for low-skilled workers:

A case study that often gets brought up by pro-immigration advocates is the Mariel Boatlift, which was the influx of Cuban refugees to Miami in the 1980s. Economist David Card’s initial analysis of the economic impact of the event purported to show no negative effects on native wages. By contrast, Borjas (2017) re-analyzed the same data and found that the influx of migrants during this event caused a wage shock to native high school dropouts, reducing their wages by somewhere between 10-30%. As expected, this finding did not come without pushback. One criticism levied against Borjas was that the March CPS dataset he used captured the growing share of African-Americans during this time period, and that the wage depression he found was really just an artefact caused by changes in racial composition (Clemens & Hunt, 2019). Borjas has already responded to this, demonstrating that the change in the racial composition in the March CPS does not coincide with the wage decline, and finding that the wage depression effect continues to hold after making adjustments for racial composition (Borjas, 2019). Yet another criticism levied against Borjas comes from Peri & Yasenov (2019), who argued that Borjas’s findings are a result of measurement error from using too small and narrow of a sample non-Hispanic high school dropouts. Peri & Yasenov’s analysis had a much larger sample and included far more subgroups as they chose to look more broadly at non-Cubans. They also utilized synthetic control method, finding no effect. Peri & Yasenov’s method might be more precise, but is it more accurate? Doubtful, since in this case it was likely an inappropriate use of synthetic control, as Monras (2021) notes:

As argued in Abadie (2020), synthetic control groups work best when the preshock period is long and the pool of donors is large. In this case, the options are a preperiod length that spans 1973–79, with a pool of donors of 33 metropolitan areas, and a preshock period of 1976–79, with a pool of donors of 43 metropolitan areas. Moreover, the number of observations in many of these metropolitan areas is small, and, hence, preshock variables are measured with error, which further complicates the use of synthetic control methods in this episode.

Additionally, using synthetic control in the case of Mariel means that the control cities must be as close of a match to the situation of Miami in every way possible except obviously when it comes to immigration, ceteris paribus or “all else equal”, if you will. Political scientist Steve Sailer pointed out, however, that this might not hold true for Miami during the 1980s, as there was a massive cocaine boom at around the same time the boatlift had occurred, and this could have served as a cloaking illusion by offsetting the wage shock that immigration would have brought. Another thing that might be worth asking is whether or not the fact that natives who are hurt by immigrants having a tendency to migrate to elsewhere also plays a role in analyzing the Mariel Boatlift, and the answer is seemingly ‘yes’. This is precisely what Monras (2021) found, that the internal migration of natives whose prospects had been hurt by immigrants explained around 50% of the wage recovery over the 1980s in Miami (Table 5). We can also see from here that accounting for internal migration clearly shows that the effect of the Miami refugees on native wages was indeed negative:

Monras notes that “This estimate implies that an increase in a metropolitan area–skill cell equivalent to 10% of the native workforce in that cell reduces wages by around 10% on impact” (p. 223). This stands in stark contrast to David Card’s own findings that immigration does not cause substantial native outflows (Card & DiNardo, 2000). The reason for these differences in findings is because Card & DiNardo used the ‘immigrants-networks instruments’ measurement technique, which is known to find very small effects on native wages and employment rates, because, as Monras explains, “internal migration responses to local shocks is related to two facts. On the one hand, immigrant shocks tend to occur in expensive locations, where, as we show, it is easy for natives to respond by relocating. On the other hand, the immigrant-networks instrument tends to give weight to small metropolitan areas close to the Mexican border, thereby resulting in lower internal mobility estimates than when other identification strategies are used” (Monras, 2021, p. 208). Another study looking into the Mariel Boatlift is Anastasopoulos et al. (2021), which utilized a historical database of job listings known as the Help-Wanted Index and found that the event resulted in a sharp decline in low-skill job vacancies, though recovery did eventually occur once enough time passed.

Empirical data aside, another way in which we know that immigration almost certainly hurts native wages is when the people who claim otherwise flip 180º on their stances. Camarota (2023) gives quite a few good examples:

Former Walmart CEO Bill Simon has complained that the company now has to pay $14 an hour. He has also called for more immigration to reduce wages and lower inflation. There are a number of problems with the increase-immigration-to-reduce-inflation argument. But what is perhaps most striking is that advocates now openly admit that immigration reduces wages for the working class, an idea they used to dismiss.

The latest immigration advocate to call for more immigration to lower wages is George Mason professor Justin Gest. Drawing on research he did for the immigration advocacy group Fwd.us, he recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal that the country needs more immigration to reduce wages and stem inflation in high-growth cities, particularly in sectors such as hospitality and construction. But Fwd.us explicitly states on its website that it is a “myth” that immigration “drives down wages.”

Gest and Fwd.us are not alone in having a change of heart when it comes to the impact of immigration. The National Immigration Forum, another leading advocacy group, now argues wages are too high and that we need more immigration to bring them down, contradicting its prior position that any concerns that immigration reduces wages “are largely overblown.” The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which used to argue that “data do not support” the idea that immigration has a sizable impact on wages, now says that doubling immigration “might be the fastest thing to do to impact inflation” by keeping wages down.

In an article for Foreign Affairs, prominent economists Gordon Hanson and Matthew Slaughter called for significantly increasing immigration to “limit wage and price growth” and help “defeat inflation.” Strangely, later in the same article, they state that immigration has only “a modest effect on the wages of native-born workers.” In an interview for NPR, University of California,

Davis, economist Giovanni Peri argued that more immigration would keep wages down and alleviate inflation. This is in stark contrast to his prior position that immigration’s impact on wages was “small and, on average, essentially zero.”

Apparently, what was once a negligible impact on wages is now a large and desirable one. In truth, there has always been ample evidence that immigration reduces wages. A comprehensive 2016 report by the National Academies of Science cites over a dozen studies showing a negative impact of immigration on wages for competing workers, particularly those with low levels of education. Subsequent research has come to the same conclusion. The only difference now is that inflation is a hot political topic, and immigration advocates are happy to offer their cause as a solution — even if it contradicts their prior talking points.

A relevant subtopic of this debate is with regards to working visas. First of all, as far as employment based green cards go, they are not the majority of the new immigrants, not even close, it’s that simple. One look at the data from the Department of Homeland Security should be enough to end the discussion on this.

Now, what about those foreign workers who have H-1B visas? Those ‘high-skilled’ immigrants that pro-immigration advocates love to praise? Well, even among them, the pay is less than for native workers, once we are appropriately comparing apples to apples, that is. It’s true that when merely comparing medians, H-1B workers seem to be high earners compared to Americans.

However, H-1B workers occupy a more narrow set of jobs than Americans do, and they are brought over here specifically because various employers want them. Thus, this comparison is not truly apples to apples. Is there a way to do better? Yes. A 2018 report from the Migration Policy Institute showed that when looking at the top 20 employers, H-1B dependent workers earn on average $30,000 less than workers who were not H-1B dependent. On top of that, only 27% of H-1B dependent workers have at least a master’s degree compared to 55% of workers who were not H-1B dependent.

Now technically, it’s true that there are provisions in place to ensure that employers are paying these workers the same as natives. However, as D’Souza (2020) explained, “a giant loophole makes companies paying $60,000 and above per employee – or hiring employees with master's degrees – exempt from this rule”. She also referenced a 2015 study from the Economic Policy Institute showing that “companies saved more than $20,000 a year per worker when they hired Indians instead of Americans”.

Aside from that article itself and the studies it cites, there’s also a more recent 2021 report from the Economic Policy Institute which revealed that H-1B dependent workers in major companies such as Disney, FedEx, Google, and others have been underpaid by at least $95 million. Another line evidence against the overhyping of H-1B dependent workers comes from a study by Doran et al. (2022), which exploited the lottery system for H-1B visas after the number of applicants exceeded the limit and found that firms that won the lottery for H-1B visas not only did not see any increase in employment relative to the firms that didn’t win, but that there was actually a crowd-out effect of 1.5 workers for every H-1B visa. The authors also found no statistically significant effects of winning the lottery on firm innovation. Another issue is that of employment itself. Contrary to the popular misconception, an employer is not required to attempt to hire native workers first before applying for a visa, nowhere is it ever stated they do. All that is needed is for a labor condition application form to be filled out and submitted for review. Only if a firm is considered H-1B dependent or has been previously caught violating the provisions (willful violator) is this applicable. So, how does this review process work? It’s short and not very comprehensive, since 8 U.S.C. § 1182(n)(1)(G) says the following:

The Secretary of Labor shall review such an application only for completeness and obvious inaccuracies. Unless the Secretary finds that the application is incomplete or obviously inaccurate, the Secretary shall provide the certification described in section 1101(a)(15)(H)(i)(b) of this title within 7 days of the date of the filing of the application.

In theory, employers must pay the prevailing wage for the occupation in the specified location for their visa workers (with the caveats previously listed), but how does the Secretary of Labor actually know that an employer filed the prevailing wage claim truthfully? That’s the neat part, they don’t! They just hope that the employer is being truthful in the application and gives him or her the green light until years later when a scandal comes up. Unsurprisingly, this doesn’t end up working out too well. The United States Government Accountability Office produced a report in 2011 investigating the H-1B visa program and found that, to the surprise of no one, the most common violation of the program was not paying the prevailing wage:

We can also see the breakdown of wage levels of approved applications. The most common were levels 1 and 2 at 54% and 29%, respectively.

Now, isn’t this a bit strange? H-1B workers are allegedly high-skilled workers who are here to fill in highly specialized roles, so why are employers reporting wage levels so skewed towards the bottom level? A 2020 report by the Economic Policy Institute finds the same thing:

Either they’re actually not that skilled, or employers just abuse the system, pick your poison. The report also looks at the top 30 H-1B employers which collectively account for more than a quarter of all approved petitions and found that a majority of them use an outsourcing business model:

Recall earlier that I said that comparing the median wage of H-1Bs to all Americans is not an apples to apples comparison. Fortunately, this report does us a huge favor by showing the distribution of wage levels of H-1B workers among H-1B employers, and from it, we can see clearly that the wage levels of those workers tend to trend towards the bottom two:

This situation resembles a case of Simpson’s paradox, whereby within a given employer, H-1B workers usually earn less than native workers, but because H-1B visas more often than not get used by extremely large employers who pay better, the aggregated result shows H-1B workers earning more than natives. Now, of course, we can debate whether or not paying H-1B workers lower necessarily translates into paying existing native workers within the same occupation and location lower. However, what is not debatable is that the visa program as it currently exists incentivizes employers to not hire Americans. Getting paid worse than you otherwise would when you’re in a job is generally considered bad, but so is not even getting hired in the first place because someone else took the job position from you. From all this, it’s clear that H-1B visas are being used by corporations for their own benefit at the expense of native workers, and there’s no reason to pretend otherwise.

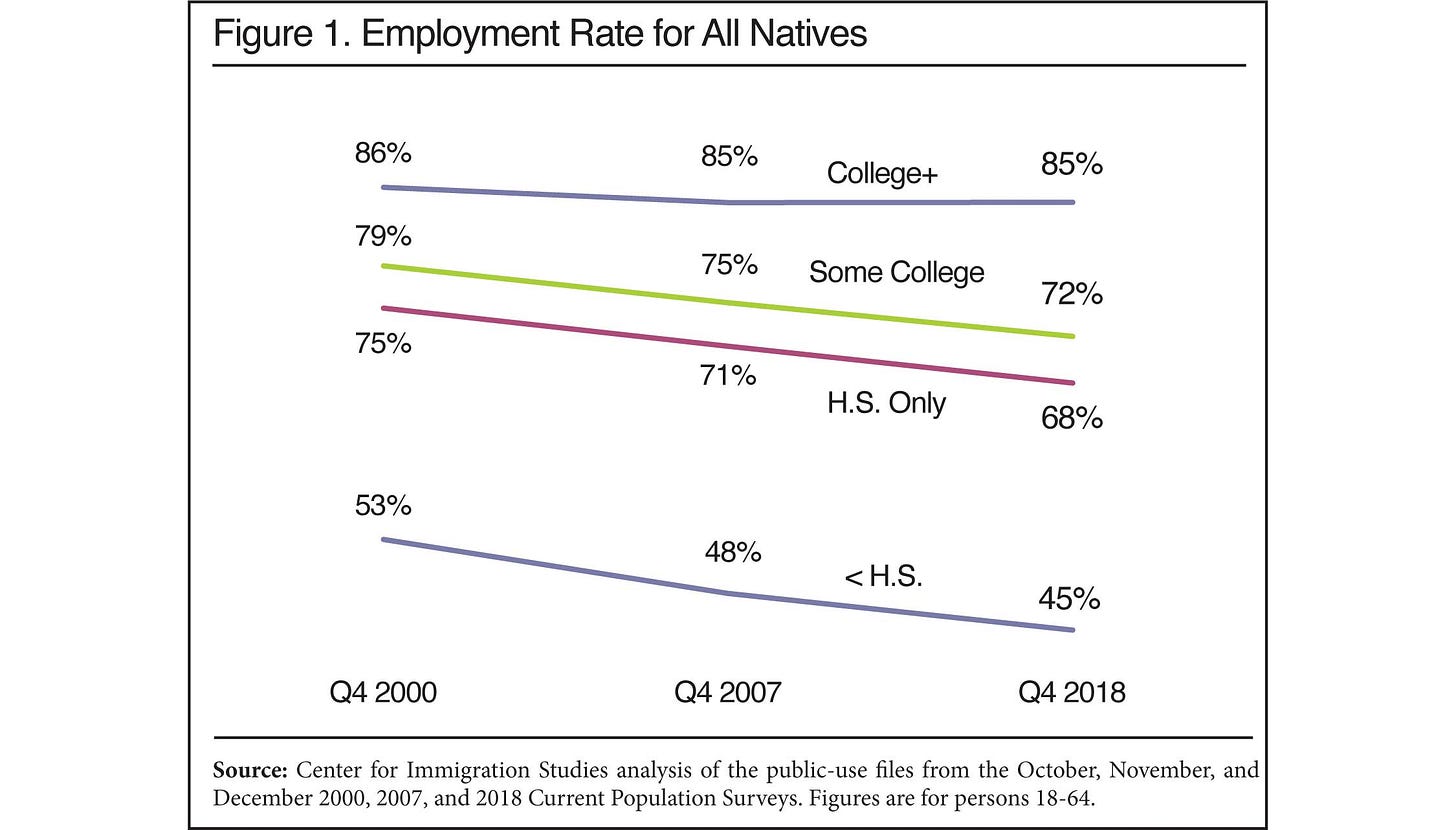

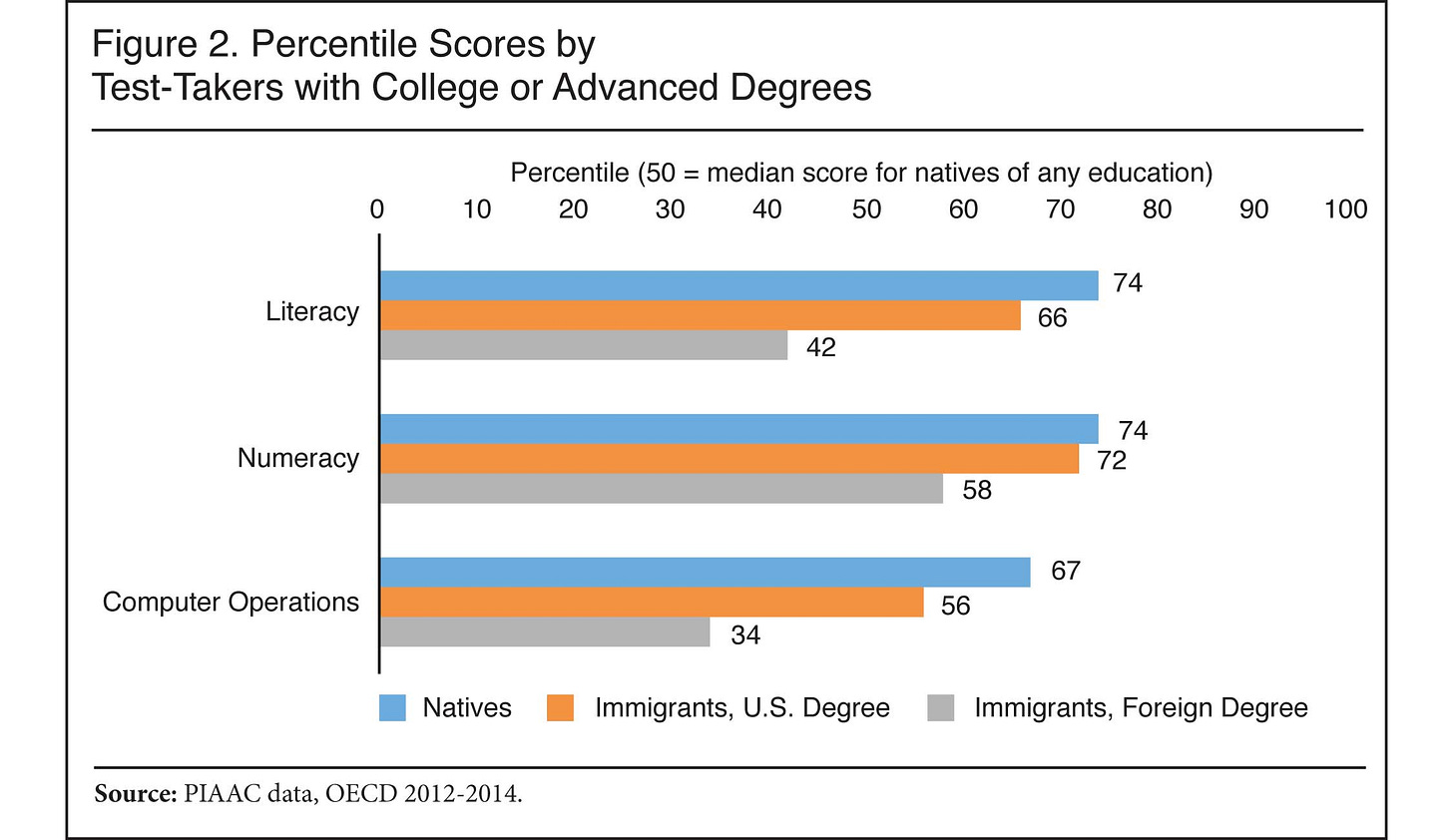

When it comes to the issue of high-skilled immigrants in general, even those immigrants can cause problems for natives. This is because the correlation between education and earnings is weaker for immigrants than it is for natives, such that when a highly educated immigrant is selected at random, he or she will have lower earnings than a less educated immigrant from the same country 24.7% of the time, whereas for natives, it’s 13.8% (Bertoli & Stillman, 2019), and so as a result, trying to recruit high-skilled immigrants by using education as a proxy might end up backfiring and hurting low-skilled natives. In reality, there’s no need to say ‘might’ in this situation because we know that it actually does, since college-educated immigrants are more likely to hold low-skill jobs compared to college-educated natives (Richwine, 2018a). Part of this can be explained by the fact that when comparing immigrants and natives with the same education level, the immigrant is more likely to score lower on tests of literacy, numeracy, and computer operation, suggesting that the earnings gap between natives and immigrants is at least partially a reflection of a skills gap (Richwine, 2022). This is also consistent with the fact that despite faster gains in education, recent immigrants have not improved on measures of income, poverty, and welfare consumption, most especially the ones from Latin America (Camarota & Zeigler, 2018a).

It’s almost certain that the debate on immigration and native wages will never be settled even decades later, but at the very least, this demonstrates that the picture isn’t as rosy as pro-immigration advocates like to paint it as, nor is the evidence as favorable to them as they claim it to be.

Scarcity

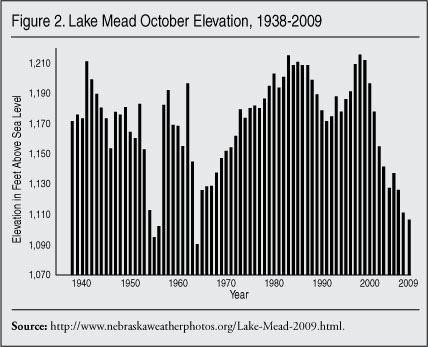

Moving on, another thing to consider is the devastating effects of immigration on the Southwestern United States, the region which is receiving the most amount of immigrants. Now, it may be worth noting that limited water usage has been a problem for the American Southwest for a long time, as the Anglos were never the best at water usage past the 100th meridian line, but this was always balanced out by the small size of the population as well as by the aquifers and rivers which tended to be proportionate to the population of the time. Unfortunately, this no longer remains to be the case. Parker (2010) shows just how dire the situation is. New arrivals are responsible for the majority of population growth in California and responsible for between 30-60% of the population growth in other Southwestern states. As a result, the region is currently facing a structural water crisis, causing too many people to live in an area that is too dry. The region is almost solely dependent on the water from just two major rivers, the Rio Grande and Colorado, as the situation requires nearly optimal precipitation all of the time to support its population in a region infamous for delivering anything but optimal precipitation, which has resulted in droughts becoming incredibly common. However, to bring light to how bad things are going to get, we only need to look at the example of Lake Mead. Here is the elevation above sea level of the lake across time:

This snippet puts into perspective the disaster that we’re heading towards if nothing is done to address this soon:

With drought, Lake Mead shrank to 1,103 feet above sea level in April 2009, rapidly approaching the record-setting low of 1,092 feet set in May 1965 as the flow was slowed to a trickle to free up water to fill the new Lake Powell upstream. It took Lake Mead 19 years to recover even though the region was not then in drought and the population was only about 30 percent of what it is today.37

By spring 2009, Lake Mead was down to 43 percent of capacity and startlingly close to the 1,075-foot elevation that is the trigger for a federal shortage declaration that would force Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico to sharply curtail water use. (By mid-summer, it was at about roughly 1,095 feet above sea level.) Critical in this picture is that in an average year with more-or-less normal snowfall in the Rockies, more water is released from Lake Mead than flows into it; in other words, “banked” water is drawn down even in average years. It takes several years with above average runoff to build up the lake’s reserves.

Lake Powell, the second largest reservoir in the nation, has taken a similar hit. A long, slender reservoir spanning the Arizona-Utah border following the rugged canyons of the Colorado River (to the north) and San Juan River (to the east), Lake Powell, after the completion of Glen Canyon Dam, took 17 years to fill with the combined waters of the Colorado, Green, and San Juan rivers.

Characterized by water surrounding archetypical desert buttes, Lake Powell reached a record low of 3,555 feet above sea level in April 2002. That was only 33 percent of the reservoir’s capacity, down from the full mark at 3,700 feet, meaning that the reservoir was within two years or less of running dry. The water flow on the Colorado in drought-parched 2002 was only 30 percent of average. Hydrologists in 2002 reported that precipitation in the Colorado River Basin was the lowest since records were begun in 1906.

Additionally, Parker notes “Today, fish and other species are more frequently the victims as rivers are sucked dry by mushrooming human demands while the Southwest’s rivers function more as elaborate plumbing systems than as rivers. But that plumbing system is what has paved the way for 60 million residents in a land that in 1925 would have been hard-pressed to have sufficient water for a few million.” Nature is being destroyed to sustain a region that was already barely sustainable before large-scale immigration. A result of this is that the residents of California, for example, are facing permanent water restrictions that have been made into official law of that state. The average citizen living there is looking down the barrel of a future where they may have to choose between taking a shower or running a load in the washer, which is a truly pathetic situation for a first-world country to find itself in. Now, you might be wondering what the situation looks like now since that report was from 2010. The answer? It’s only gotten worse since:

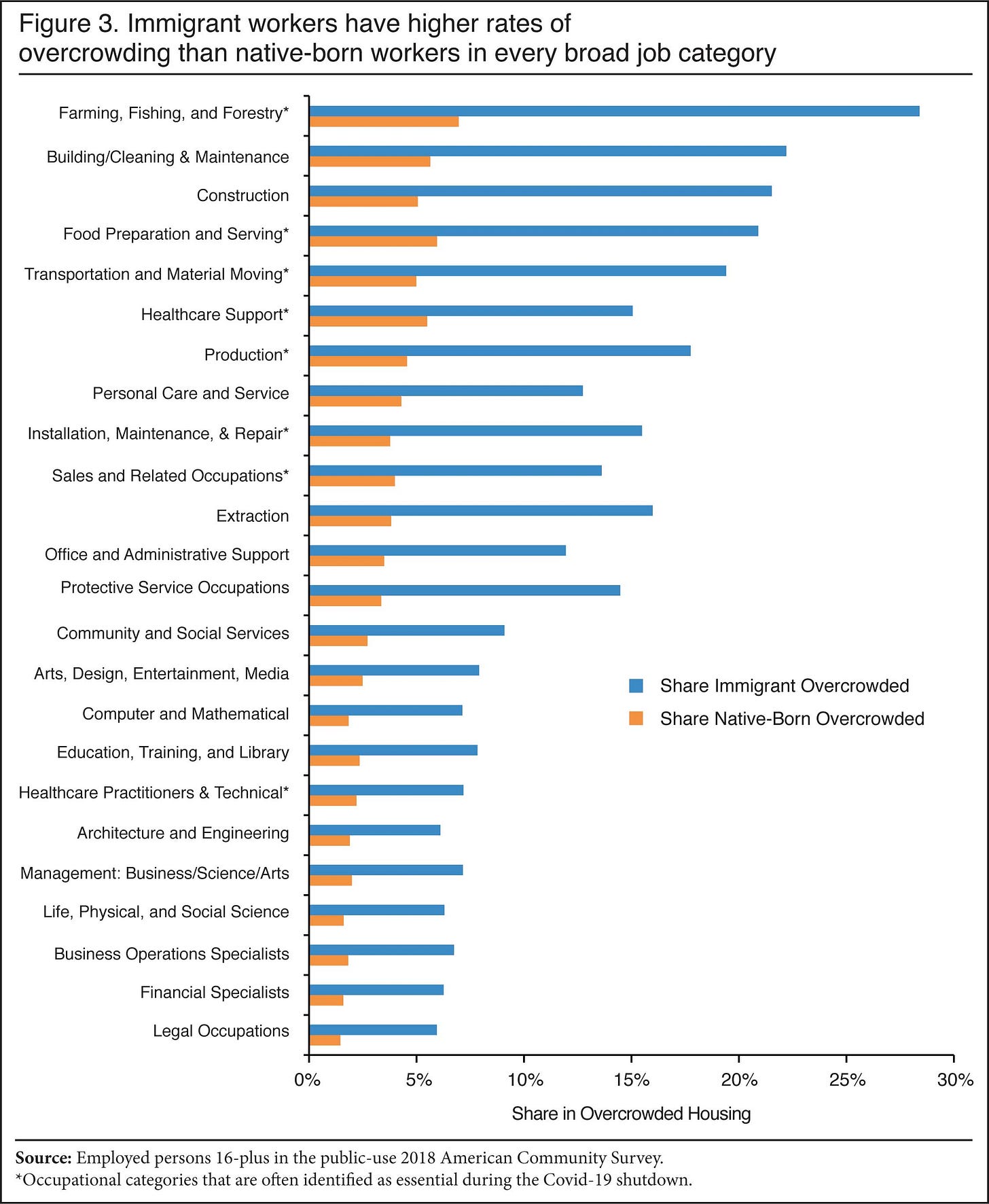

Downstream from this, the other problem that this immense population growth driven by immigration is going to be in housing. Coastal cities like San Diego, Los Angeles, and Portland have become overrun with homeless people, many being immigrants (Cadman, 2018; Camarota, 2019; Arthur, 2022). When you increase a country’s population by a million people without the ability to sufficiently increase the supply of housing to keep up the pace, the result, to the surprise of no one, is that price of housing goes up. What’s happening in many large West Coast cities is what happens when the demand increases and the supply cannot increase. Not only that, but immigrants comprise a disproportionate share of workers who are in overcrowded conditions (Camarota & Zeigler, 2020). Below is the share of overcrowding between immigrants and native-born workers in various job categories:

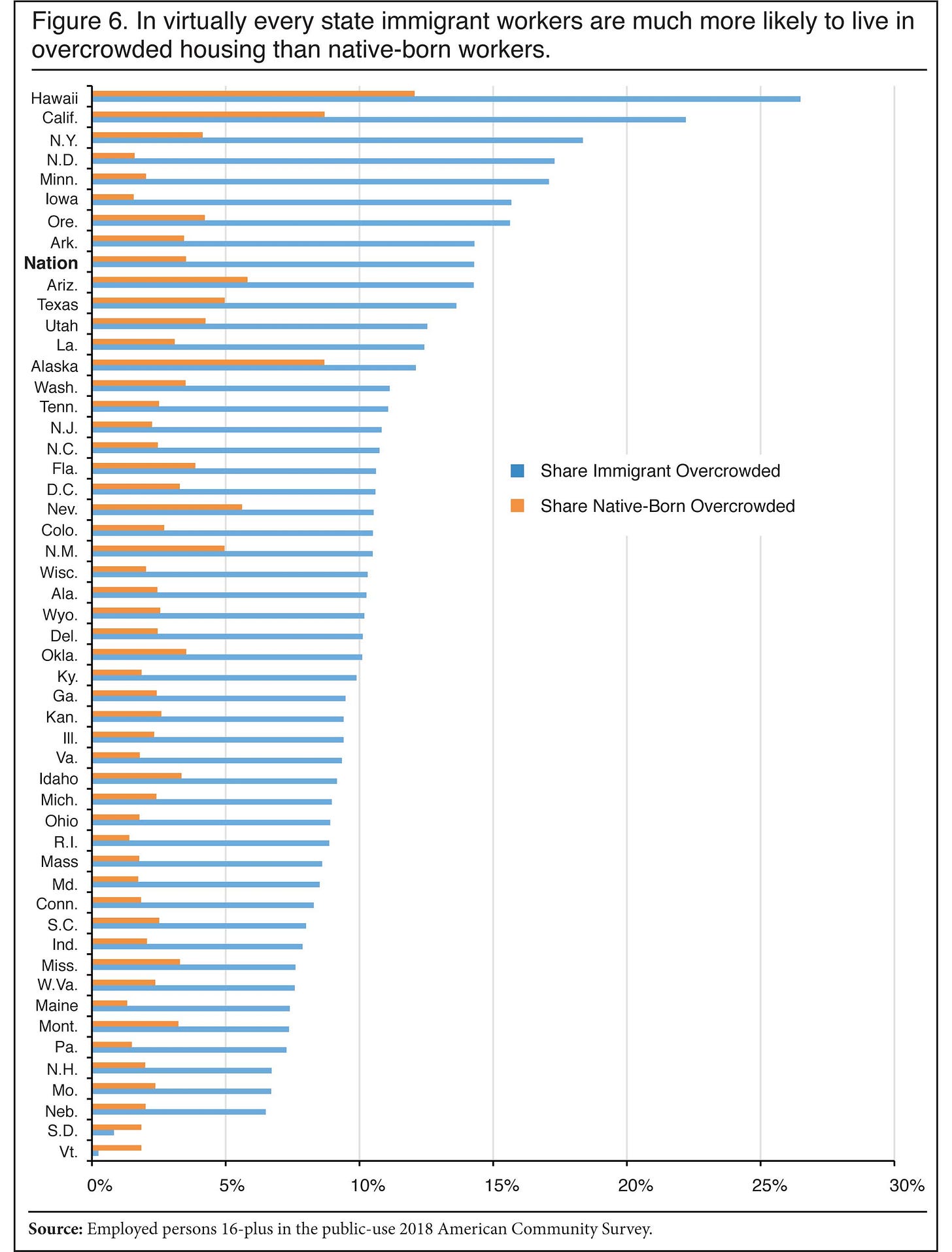

Across nearly every state, immigrants are more likely to live in overcrowded housing compared to native-born workers:

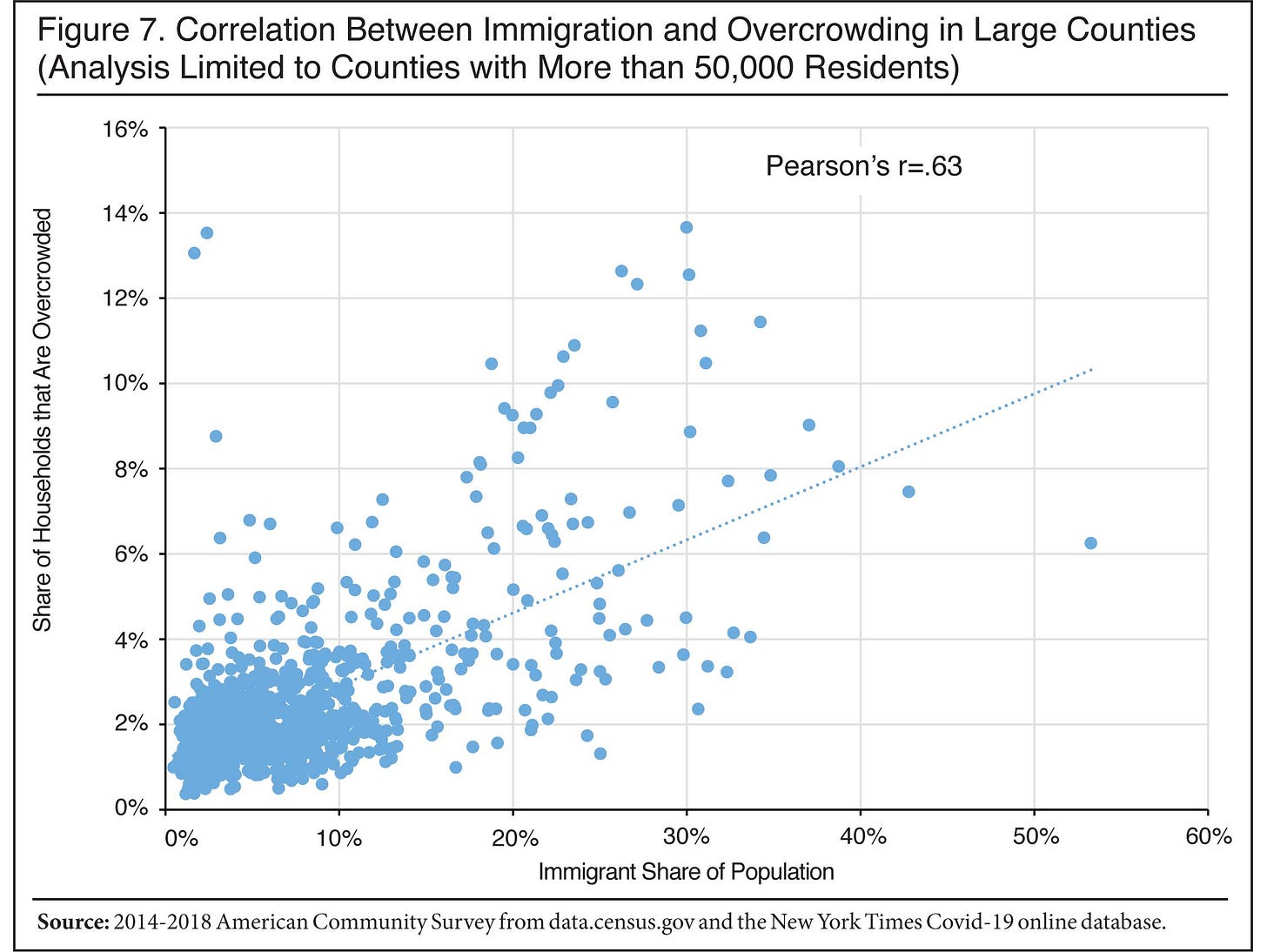

In fact, the percentage immigrant correlates with overcrowding in large counties at 0.63:

In the case of the United States, it’s been found that a 1% increase in immigration results in increasing rent prices by 1% (Saiz, 2007). A more recent study, Mussa et al. (2017), finds that a 1% increase in immigration in a metropolitan statistical area (MSA) increases rent prices by 0.8%. However, when indirect effects were included, this doubled to 1.6%. Upon seeing this, one might be inclined to object to these findings. Haven’t tons of studies found that immigration doesn’t really affect housing prices? Sure, but it’s for the same reason why they also don’t find any effects on wages; using poor measurement techniques which cannot fully capture the effect of immigration biases the result towards zero. As is the case with wages, accounting for the internal migration of natives reveals that unsurprisingly, immigration does indeed place a substantial strain on housing prices (Monras, 2021). That’s a pretty grim picture. Seeing as to how dire the situation currently is with immigrants, there’s no reason why we should be bringing in even more of them, considering they’ll almost certainly make the problem worse.

Welfare Use and Fiscal Impact

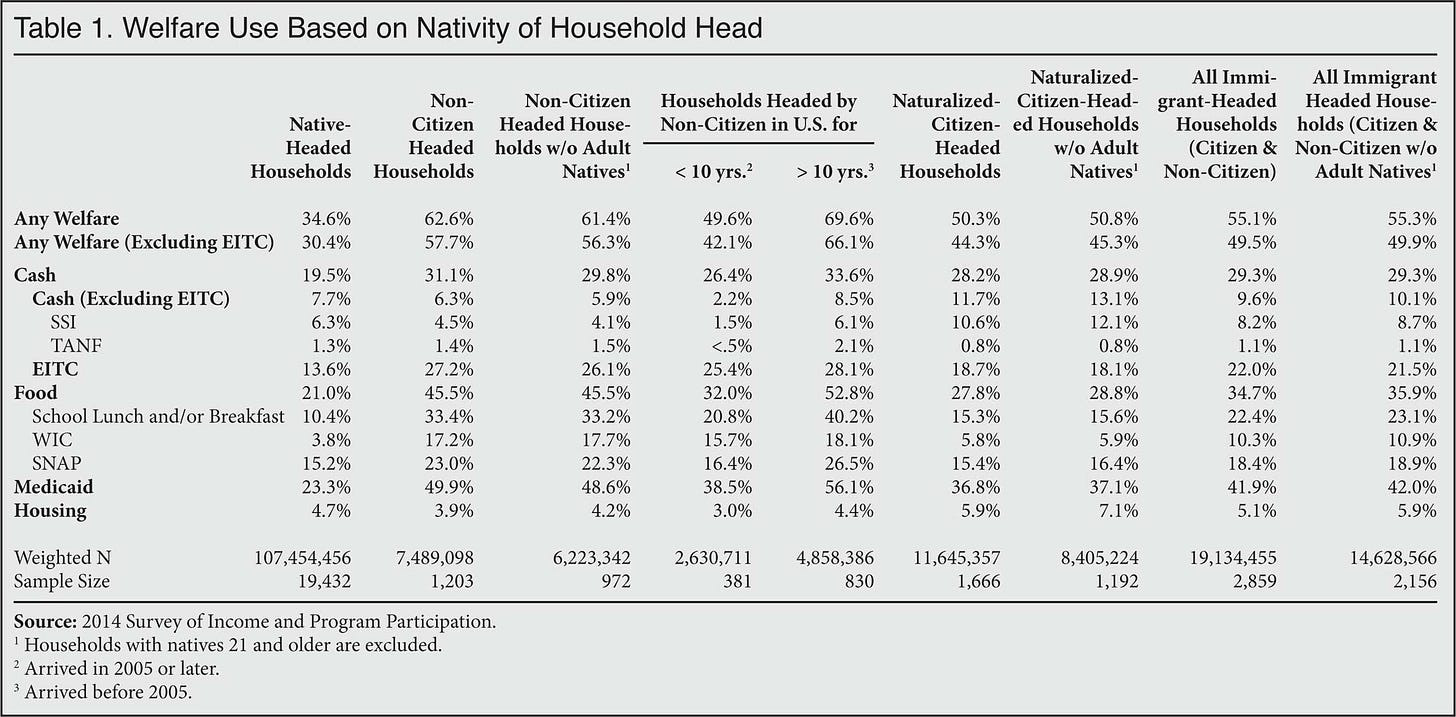

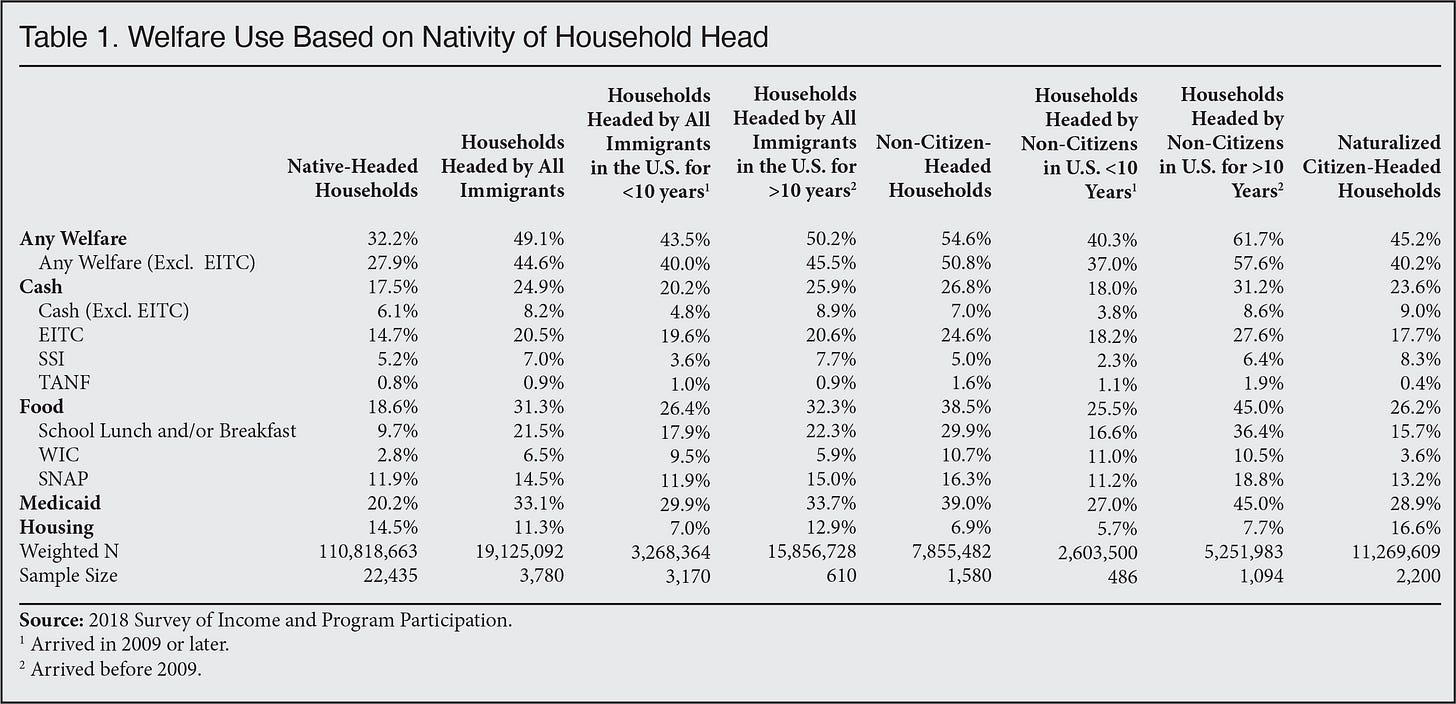

Another and more common argument used against immigration is welfare use, and this is true, immigrants do disproportionately use more welfare than natives (Camarota & Zeigler, 2018b). In 2014, 55.3% of immigrant-headed households reported that they used at least one welfare program during the year, compared to 34.6% of native households.

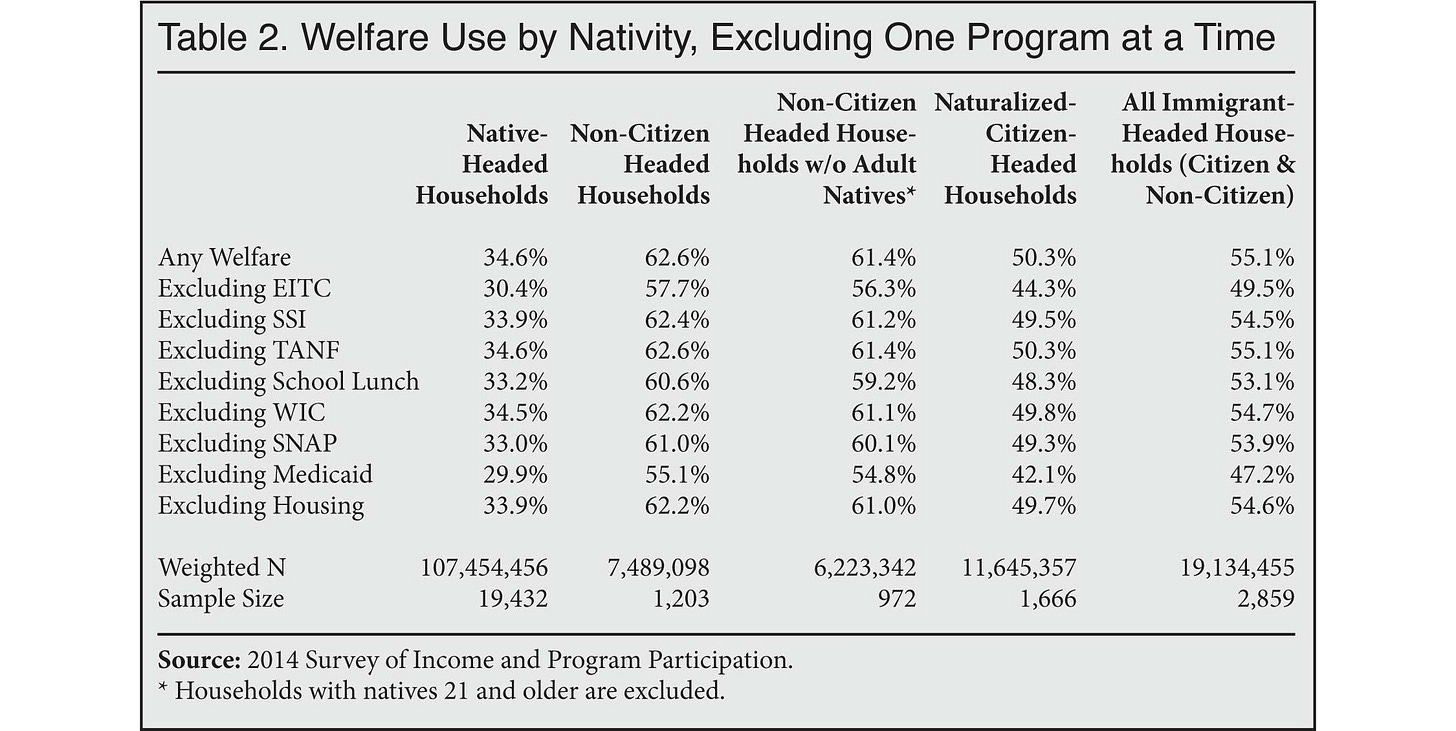

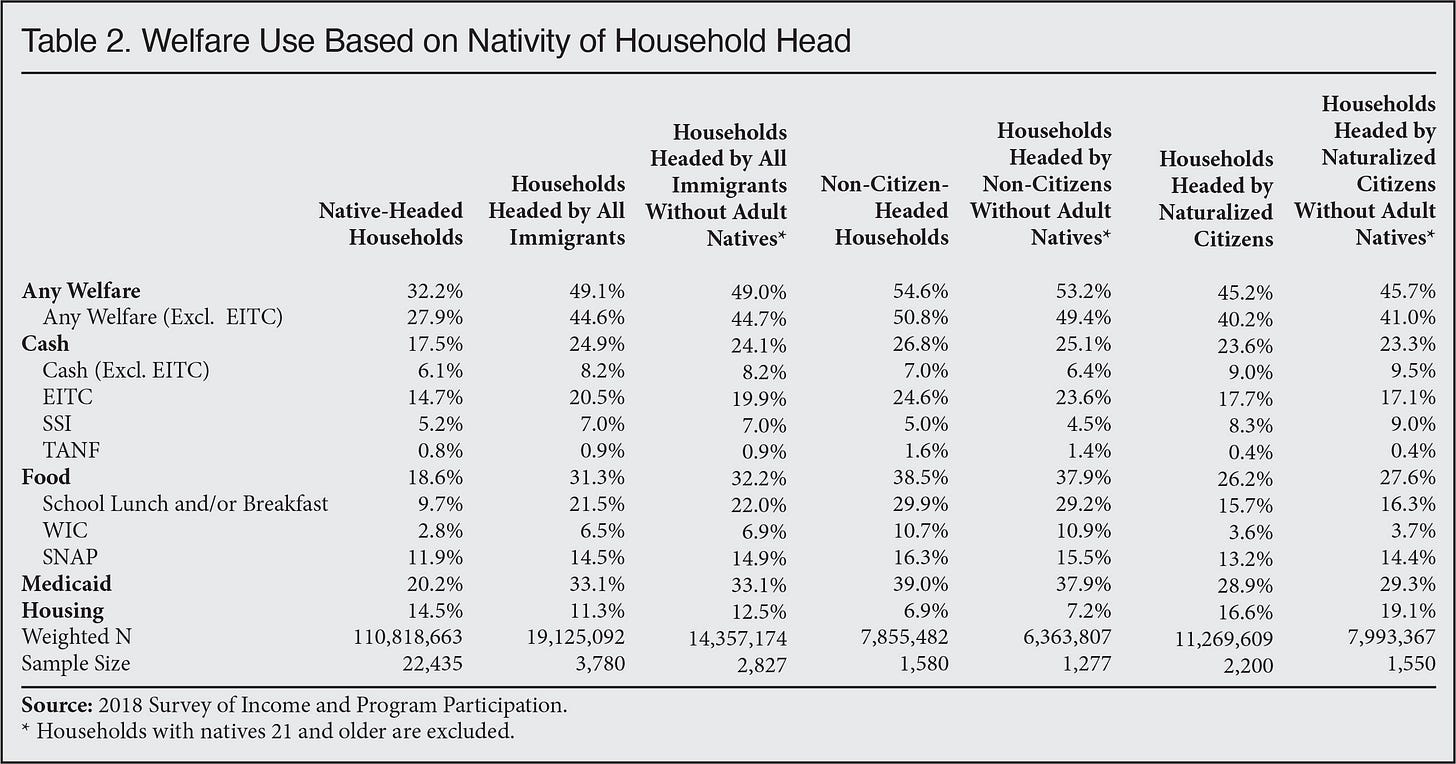

Regardless of which welfare program you choose to exclude, the welfare use of immigrants of any kind remains higher than their native counterparts:

Welfare use among both non-citizen-headed households and naturalized-citizen-headed households are also higher than their native counterparts within the same education level:

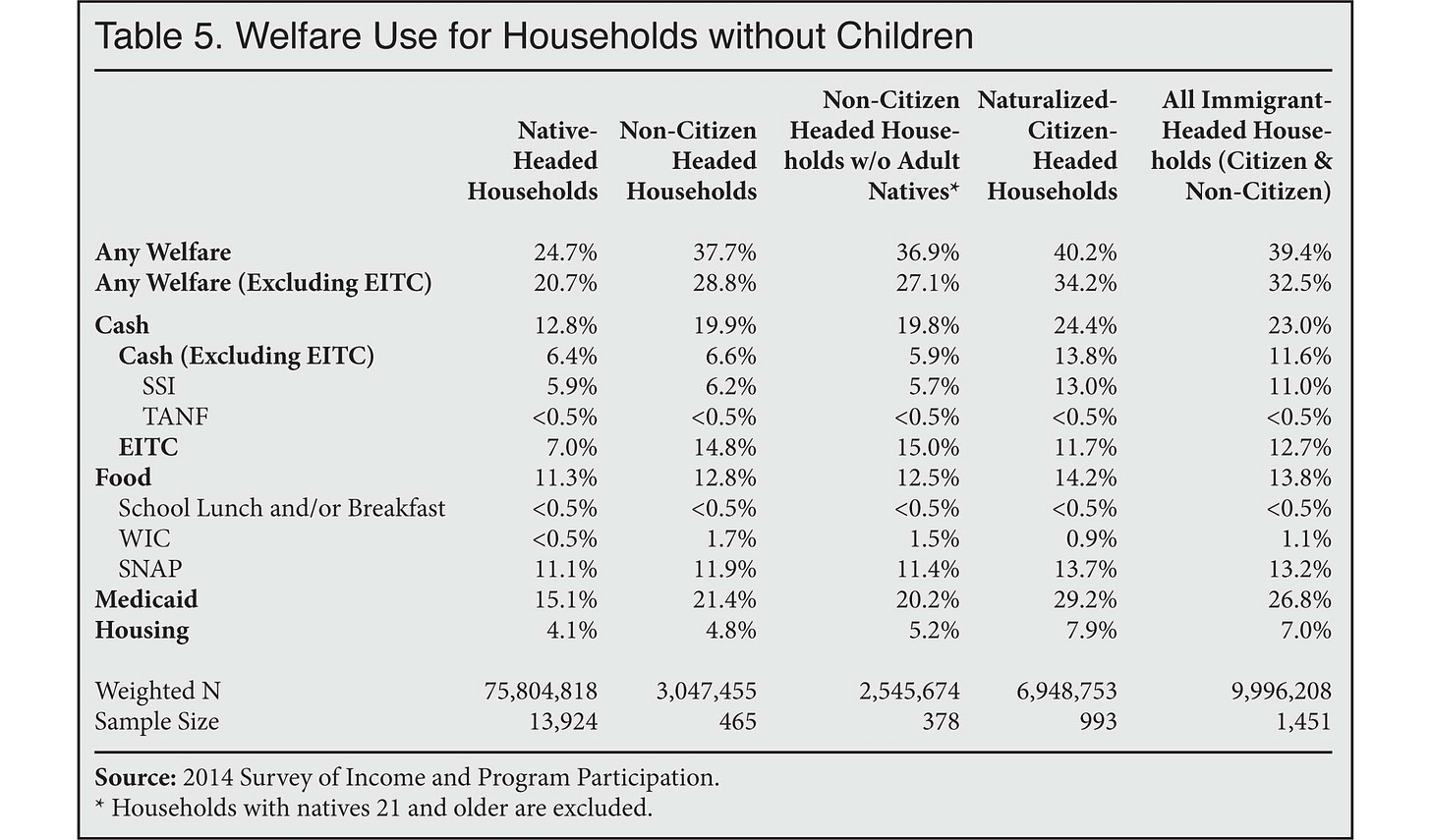

Perhaps this is because immigrants are trying to support their children, but when we look at immigrant households without children, they still use significantly more welfare than native households without children (and the percentages are actually higher than the 34.6% of native-headed households):

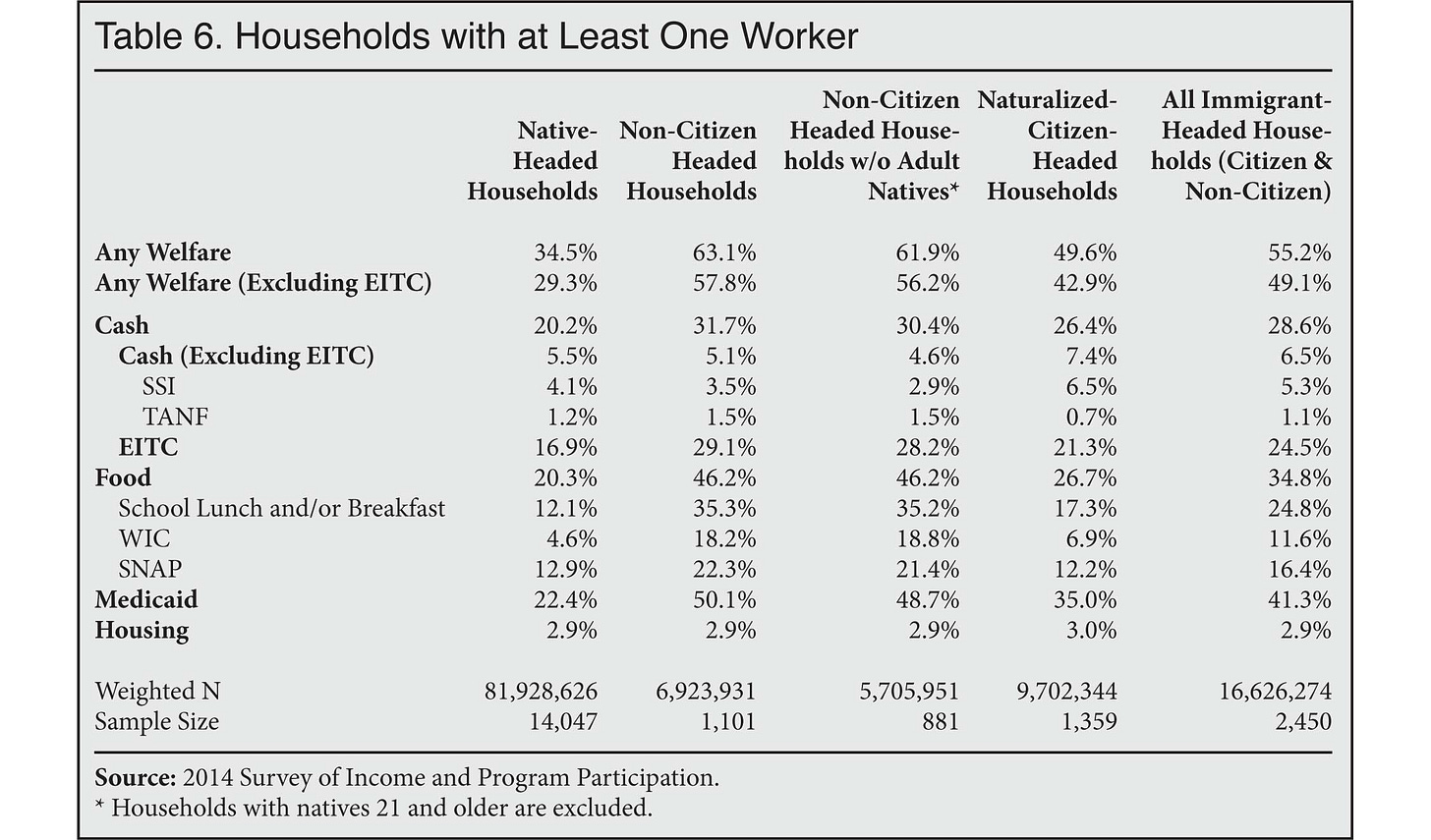

This trend still holds true when looking at immigrant households with at least one worker:

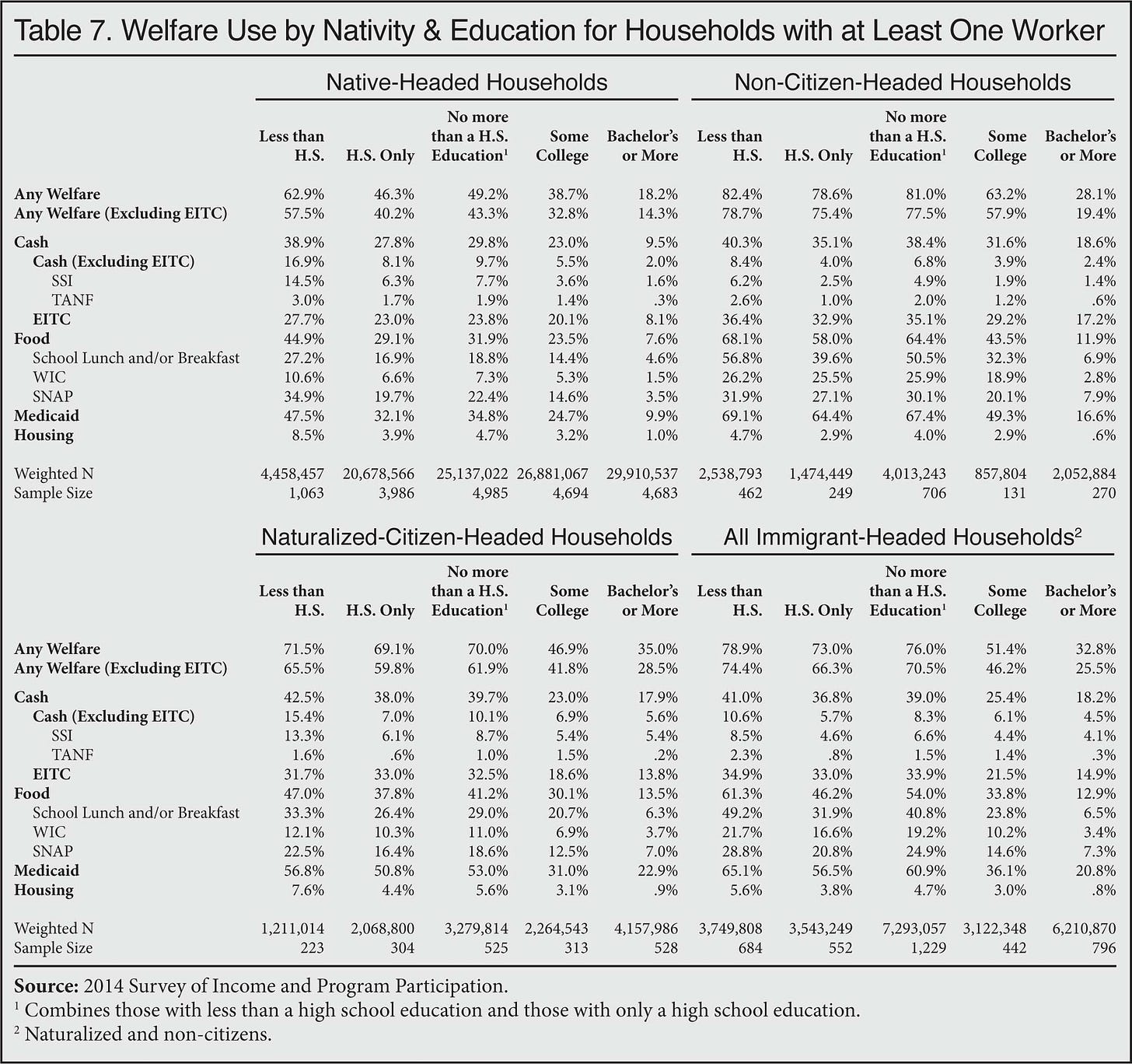

Even if we look at immigrant households with at least one worker and by education level, they use more welfare than do native households:

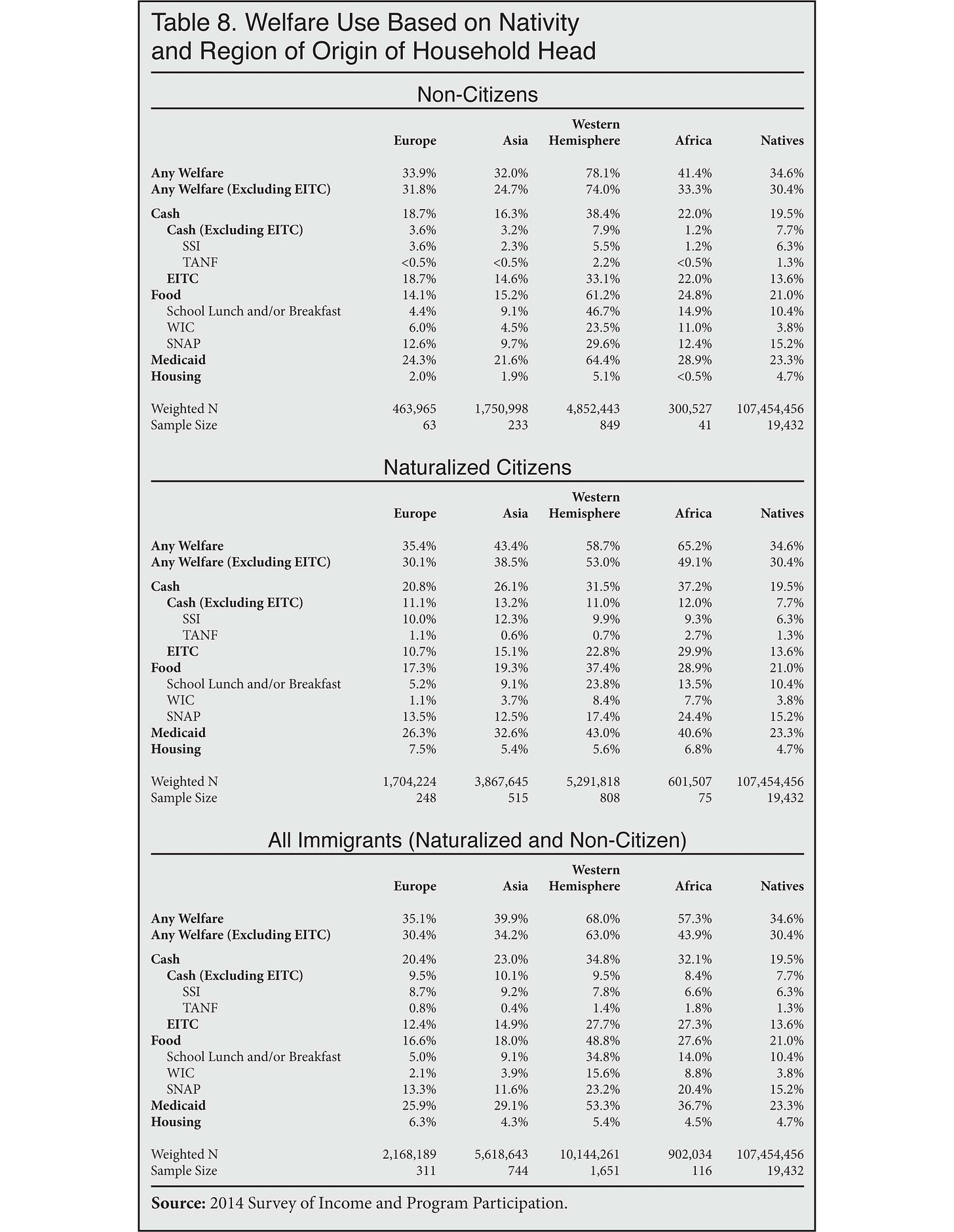

There is no scenario in which welfare use isn’t higher among the immigrant household compared to native households of the same circumstances. When we break down the welfare use of immigrants by region of origin, suddenly the high welfare usage makes a lot of sense, can you guess why?

Unsurprisingly, the high rates of welfare use are primarily driven by those from Africa and the ‘Western Hemisphere’ (i.e., Latin America). A more recent version of this report is also available for the year 2018, and again, the trend of immigrant households using more welfare than native households holds, regardless of the circumstances of the immigrant households (Camarota, 2021a):

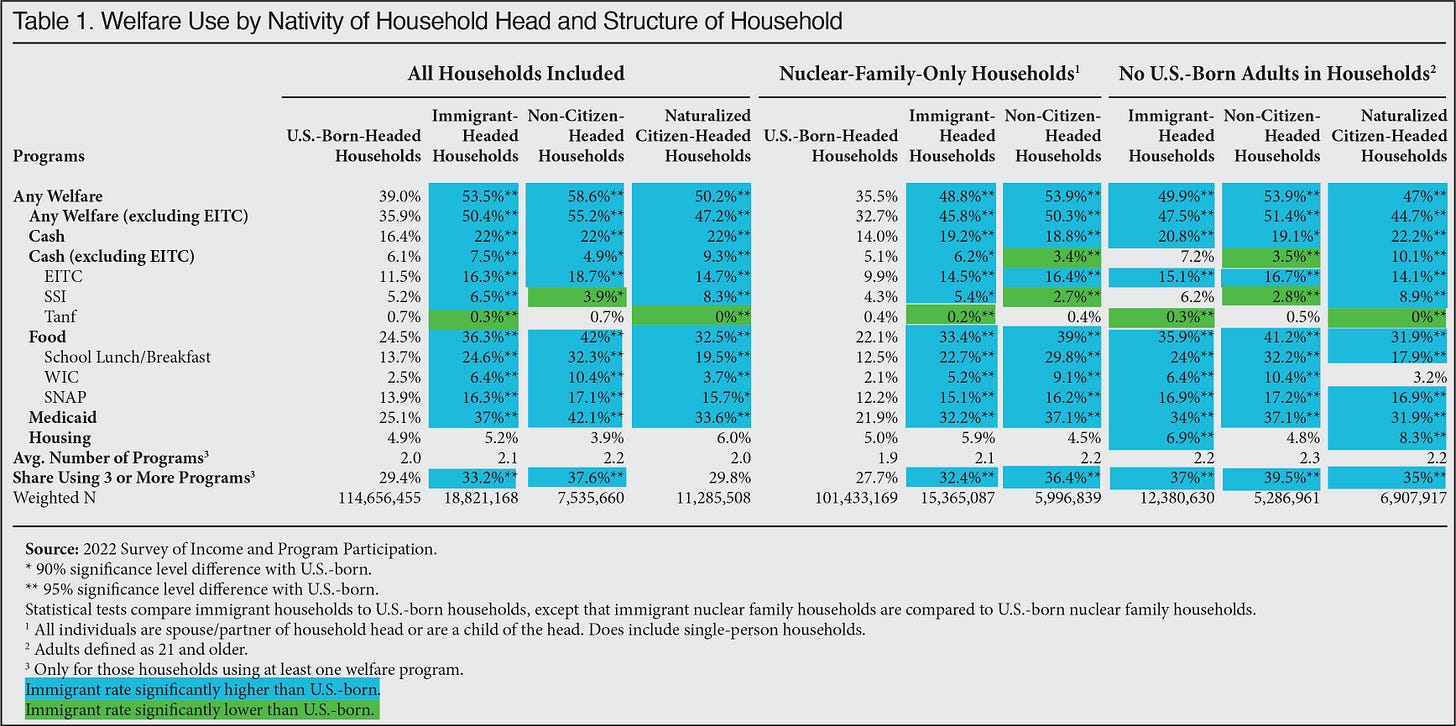

Currently, the most recent version of this report is for the year 2022, and again we see that the same pattern holds (Camarota & Zeigler, 2023a):

A neat thing about this report is that it also specifically looks at the welfare use of impoverished households separately. As expected, when welfare use is much higher among both natives and migrants who are 250% below poverty, but the welfare use of immigrants is still higher:

Another neat aspect of this report is that it breaks down the welfare use of natives and immigrants by age of household heads, which is helpful since the age composition of natives and immigrants differ, so we can examine whether or not age differences explains the higher rate of welfare use among migrants, and it seems like that’s not the case.

For the most part, it seems that the welfare use of immigrants is always higher than their native counterparts except for the cases where the heads are under the age of 25, but the catch is that very few households are actually this young, as the report notes that only about 4.5% of native households and 2.8% of immigrant households are have a head under the age of 25.

And of course, just like before, guess who’s using the most welfare when looking at it by race? Once again, blacks and Hispanics, completely unsurprising.

All of these estimates were derived using data from the Survey for Income Participation Program (SIPP). This is important because different surveys will produce different results. The Cato Institute for example, used the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplements (ASEC) in its 2013 report which purported to show that immigrant welfare users consume fewer welfare dollars than native welfare users. The problem however, is that the ASEC suffers from recall bias due to the way it’s designed, as Richine (2016b) explains:

The ASEC is a simple cross-sectional dataset widely used in labor market research. However, the ASEC substantially undercounts welfare participation, in part because it asks respondents to recall their welfare use over a period between three and 15 months before the interview takes place. To address the undercount problem, CIS used a more complex dataset called the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). As the name implies, the Census Bureau specifically designed the SIPP to measure participation in government programs. In addition, the SIPP is a "longitudinal" dataset, meaning it follows the same respondents over time, asking them about their monthly program participation in three different interview "waves" throughout the year. The result is a much more complete picture of welfare participation compared to what the ASEC provides.

Moreover, this Cato report only looked at individuals with low incomes, so it is not capturing the welfare use among all immigrants and all natives. Thus, the Center for Immigration Studies is using a much better source for its estimates on welfare use. Below is the comparison of the estimates derived from using the SIPP versus the ASEC in 2012:

Now, this might beg the question of how much immigrants contribute to the economy. So fine, they might use a lot more welfare than do natives, but surely this wouldn’t be a problem if they made up for it, right? So do they? The answer seems to be ‘no.’ Camarota (2004) found that if illegal immigrants were legalized and began to pay taxes and use services like households headed by legal immigrants with the same education levels, the annual net fiscal deficit would increase to $29 billion, or $7,700 per household at the federal level. Aside from that report, Camarota (2013b) analyzed the fiscal and economic impact of immigration, and the results are also extremely negative, as you can read for yourself below:

Impact on Aggregate Size of Economy

George Borjas, the nation's leading immigration economist estimates that the presence of immigrant workers (legal and illegal) in the labor market makes the U.S. economy (GDP) an estimated 11 percent larger ($1.6 trillion) each year.1

But Borjas cautions, "This contribution to the aggregate economy, however, does not measure the net benefit to the native-born population." This is because 97.8 percent of the increase in GDP goes to the immigrants themselves in the form of wages and benefits.2

Impact on Wages and Employment

Using the standard to textbook model of the economy, Borjas further estimates that the net gain to natives equals just 0.2 percent of the total GDP in the United States — from both legal and illegal immigration. This benefit is referred to as the immigrant surplus.3

To generate the surplus of $35 billion, immigration reduces the wages of natives in competition with immigrants by an estimated $402 billion a year, while increasing profits or the incomes of users of immigrants by an estimated $437 billion.4

The standard model predicts that the redistribution will be much larger than the tiny economic gain. The native-born workers who lose the most from immigration are those without a high school education, who are a significant share of the working poor.

The findings from empirical research that tries to examine what actually happens in response to immigration aligns well with economy theory. By increasing the supply of workers, immigration does reduce the wages for those natives in competition with immigrants.

Economists have focused more on the wage impact of immigration. However, some studies have tried to examine the impact of immigration on the employment of natives. Those that find a negative impact generally find that it reduces employment for the young, the less-educated, and minorities.

Immigrant Gains, Native Losses

Recent trends in the labor market show that, although natives account for the majority of population growth, most of the net gain in employment has gone to immigrants.

In the first quarter of 2013, the number of working-age natives (16 to 65) working was 1.3 million fewer than in the first quarter of 2000, while the number of immigrants working was 5.3 million greater over the same period. Thus, all of the employment growth over the last 13 years went to immigrants even though the native-born accounted for two-thirds of the growth in the working age population.5

The last 13 years have seen very weak employment growth, whether measured by the establishment survey or the household survey. Over the same time period 16 million new immigrants arrived from abroad.6 One can debate the extent to which immigrants displace natives, but the last 13 years make clear that large-scale immigration does not necessarily result in large-scale job growth.

As is the case with welfare use, different methods will produce different results. Using the Cato Institute as an example again, their methodology is extremely disingenuous. In their 2023 report on the fiscal impact of immigrants in the United States for instance, Cato chooses to analyze individuals rather than by households, and they choose to count the children of immigrants as natives. This is problematic because children are obviously going to be a fiscal burden initially and it won’t be until several years later when they reach adulthood that they will be able to contribute to the economy. They are also an expense that only got here because their parents were allowed into the country in the first place. Additionally, there are, at least in theory, restrictions imposed on the ability of new arrivals to access welfare programs, but their children who are legally natives do not face such restrictions, and so if immigrants were getting access to welfare programs via their children, then Cato’s analysis will instead count this codependency as an expense on the part of natives, and it doesn’t take a genius to know why doing so is deceptive. Of course, Cato has justifications for it, just not very good ones, especially since people who actually understand this care about race and not the legal status, the legal status isn’t some magical wand that suddenly turns poor dumb people from failed states into elite human capital.

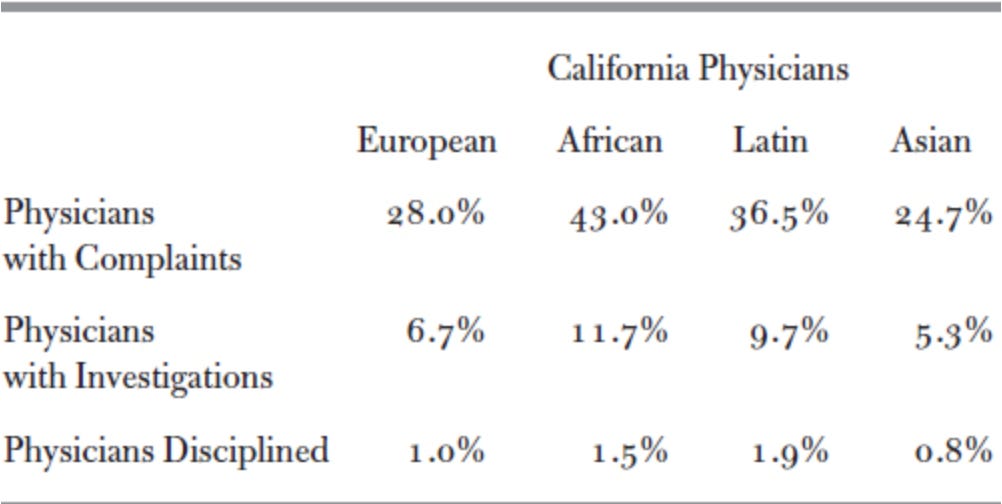

All of these reports suffer from the same problem so far however, that being what services are included in calculating fiscal impact. The concept of fiscal impact is simple enough in theory, it’s just taxes paid deducted by services used, but what counts as a service? Is it just means-tested welfare? Any sort of government program that results in the redistribution of wealth? Or, perhaps a third method which more accurately reflects the real-world situation, “services” are not merely official programs intended to redistribute wealth, but also anything the government provides which has a cost attached to it. In the real world, someone’s costs isn’t merely derived from their welfare use, if someone commits a crime and ends up in prison, well then prison maintenance is a cost that they’ve incurred. The same would be true for things like law courts, police, and public transit. Another thing we might want to consider is to analyze the fiscal impact by race rather than legal status, as that’s likely to play a much greater role. Doing it this way, Faulk (2020) analyzed the fiscal impact by race in 2018 by including government services in addition to welfare programs and found that the budget deficit in the United States is on aggregate driven by blacks and Hispanics. The results here are in billions of dollars:

We can see here very clearly that blacks and Hispanics are a massive net negative, whereas whites and Asians are a net positive. When people are concerned about immigrants, they’re usually not thinking about Norwegians or Japanese, they’re thinking about the ones from Latin America, and to that end, they’re completely justified in those concerns. Here’s something quite telling from Ryan’s analysis: even if you assigned all military spending costs to whites, they would still be running a slight budget surplus.

If the 1965 Hart-Celler Act was never passed and we didn’t welcome the invasion of the third world, the American economy would probably be stronger today and the debt would be far more manageable.1

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine had published a report originally in 2016 (updated in 2017) which concluded that “immigration has an overall positive impact on long-run economic growth in the U.S.”, but as CIS (2016) shows, their own results warrant a far more nuanced and cautious conclusion. Right off the bat, in every single one of their eight scenarios, immigrants have a negative fiscal impact, with the drain being as large as $299 billion. Second and third-generation immigrants are also net fiscal deficits, according to this report. Even when looking at it at the state and local levels where the budget is more balanced, immigrants still tend to be a net burden while natives are not. The estimated lifetime fiscal impact of immigrants based on their educational attainment, if we were to average out their estimates and apply them to the educational level of illegal immigrants, would amount to a drain of $65,292 per illegal, and this is excluding any costs for their children mind you. If we assume a population of 11.43 million illegal immigrants in 2017 (which was the government estimate at the time), then this translates into a total lifetime fiscal drain of $746.3 billion. For comparison, the cost of deportation in total would be about $124.1 billion (Camarota, 2017a). One particularly noteworthy aspect of this report is the fact that it estimates that the actual benefit of immigration to the native-born population could be $54.2 billion a year. But wait, what do we mean by ‘benefit’ in this case? CIS did some quick calculations, and here’s how they did it:

The report states that the economy (GDP) is $17.5 trillion and 65 percent is labor. Immigrants are 16.5 percent of labor so natives are 83.5 percent of labor (p. 128). This means that the total labor income of natives is $9.498 trillion ($17.5 trillion times 65 percent times 83.5 percent). A 5.2 percent reduction in native wages equals $493.9 billion and the benefit to employers is 548.1, for a surplus of $54.2 billion.

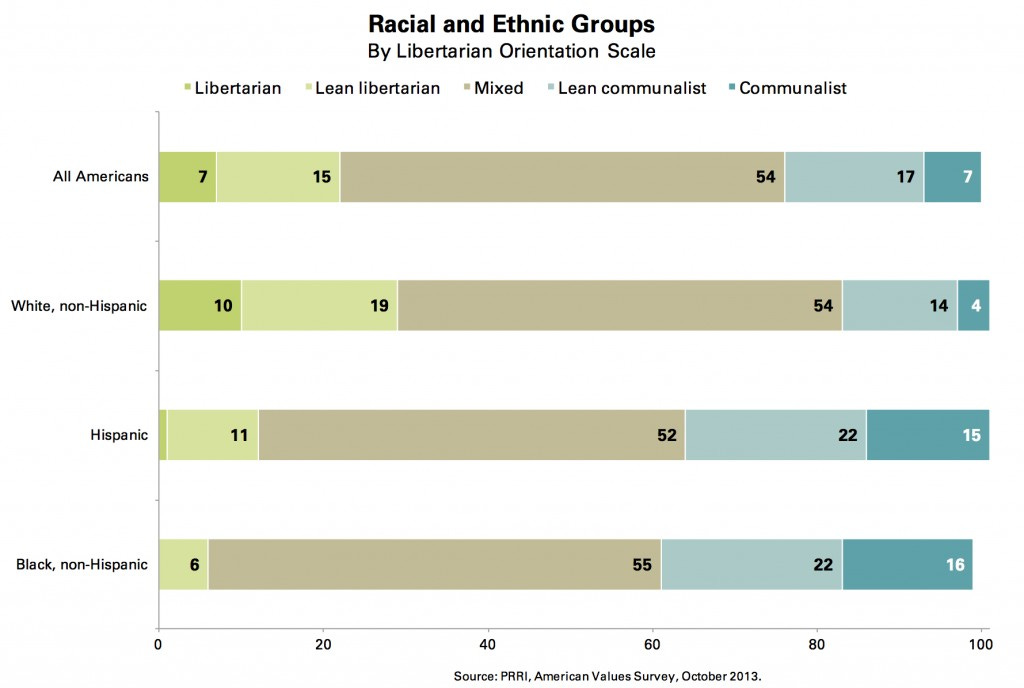

In other words, this ‘benefit’ to the natives would come from reducing the wages of native workers who are in competition with immigrants by $439.4 billion annually, but the gain to businesses would be $548.1 billion, which would create a net ‘benefit’ of $54.2 billion to natives. Whether or not most people would actually consider this as a benefit though might be a slightly different story. Now, interestingly enough, this report also provides eight different scenarios for the projection of the future fiscal impact of immigrants over the next 75 years. Of these, four come out negative again, and four do not. The problem with their scenarios where the future projection of the fiscal impact of immigrants is not negative is that it relies on assumptions for the future which cannot be safely argued to hold true, such as that federal spending will get restrained or that future immigrants will be more skilled than the current ones. Regarding the possibility of restraining federal spending, the problem with this is that the more immigrants we take in, the less likely it is that the welfare spending will get reduced as non-whites are much more likely than whites to both support wealth redistribution and bigger government, meaning that they will make the budget deficit more and more difficult to solve in the long run, not just merely due to their presence in the country but also due to how they’re going to vote (Cox et al., 2013; Faulk, 2016a).2

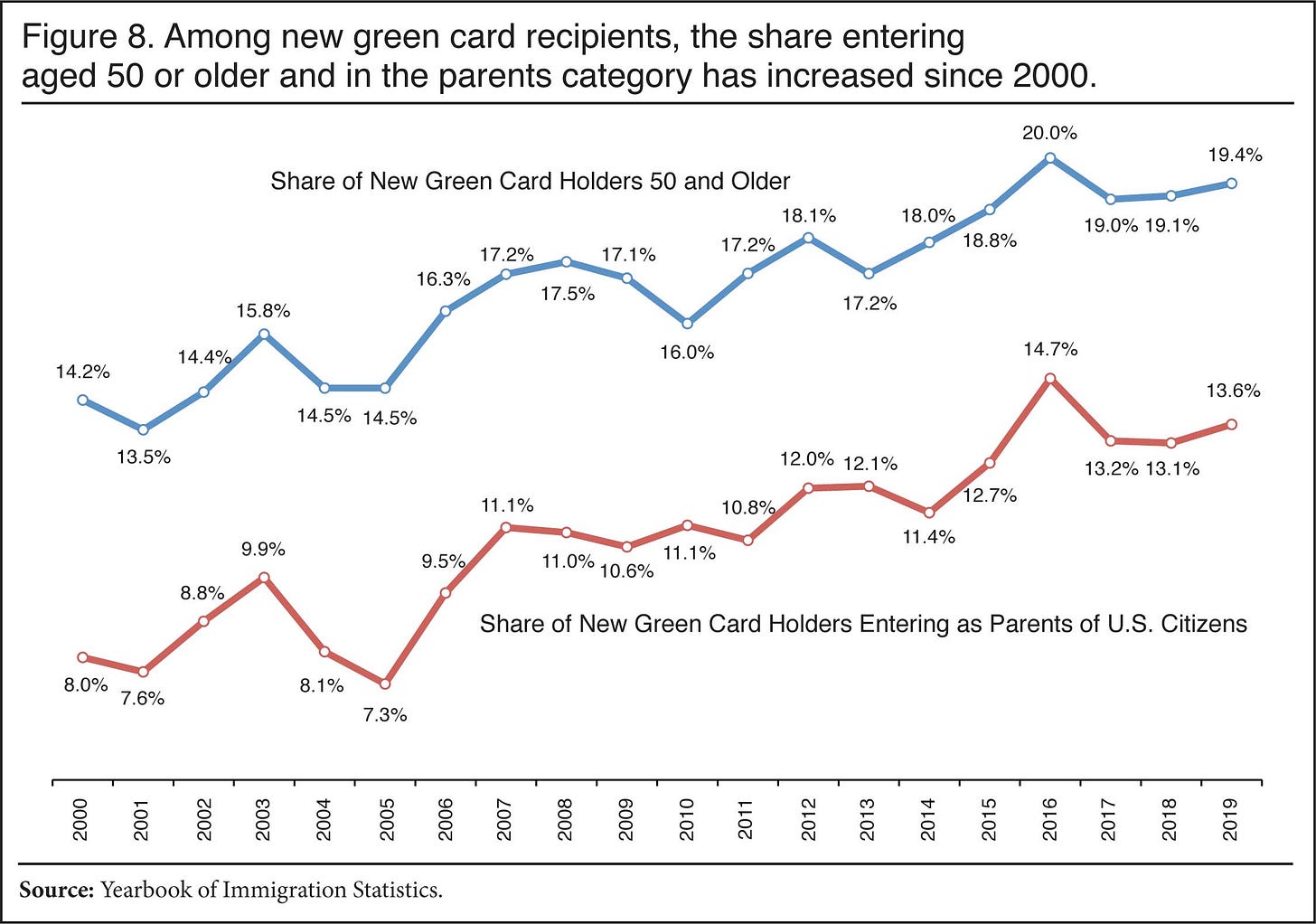

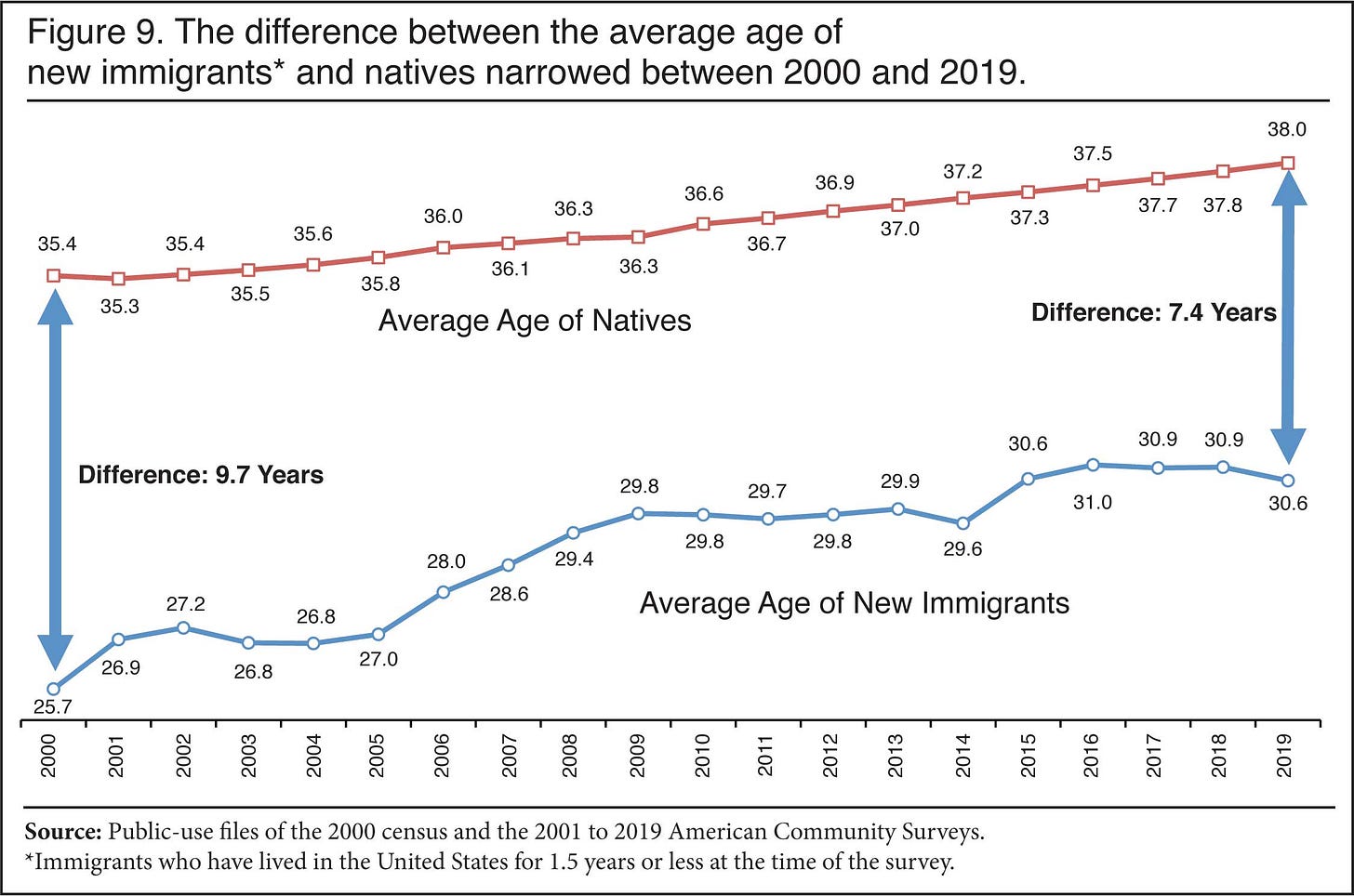

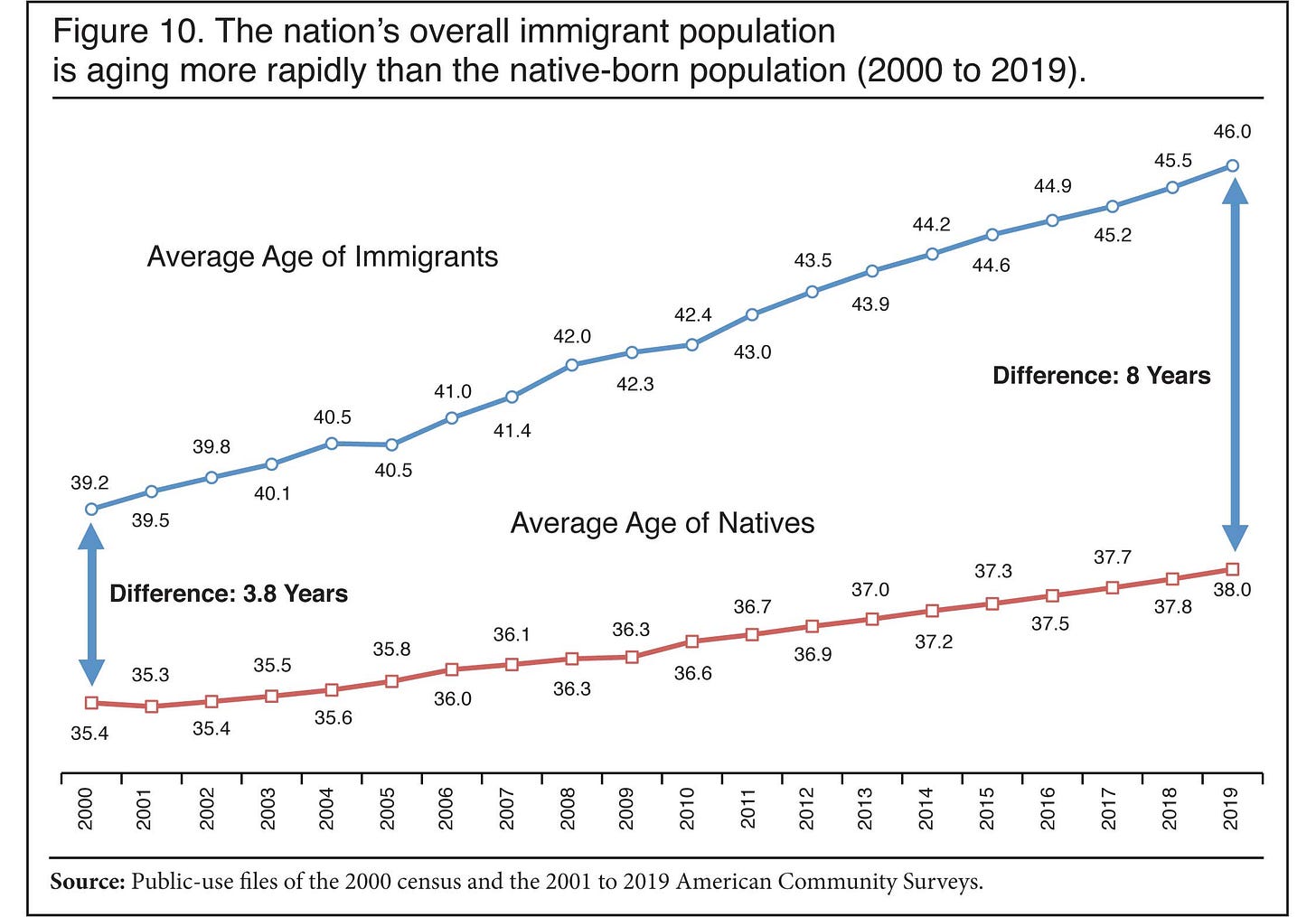

With regards to the skill of future immigrants, the problem is that immigrants are coming in at older ages now, as the number of immigrants aged 65 and above has increased by 126% between 2000 and 2019, which is much higher than the increase in the number of working-age immigrants aged 18 to 64 of 42%. Among those with a green card, the percentage who are aged 50 or older has increased over time (Camarota & Zeigler, 2021a):

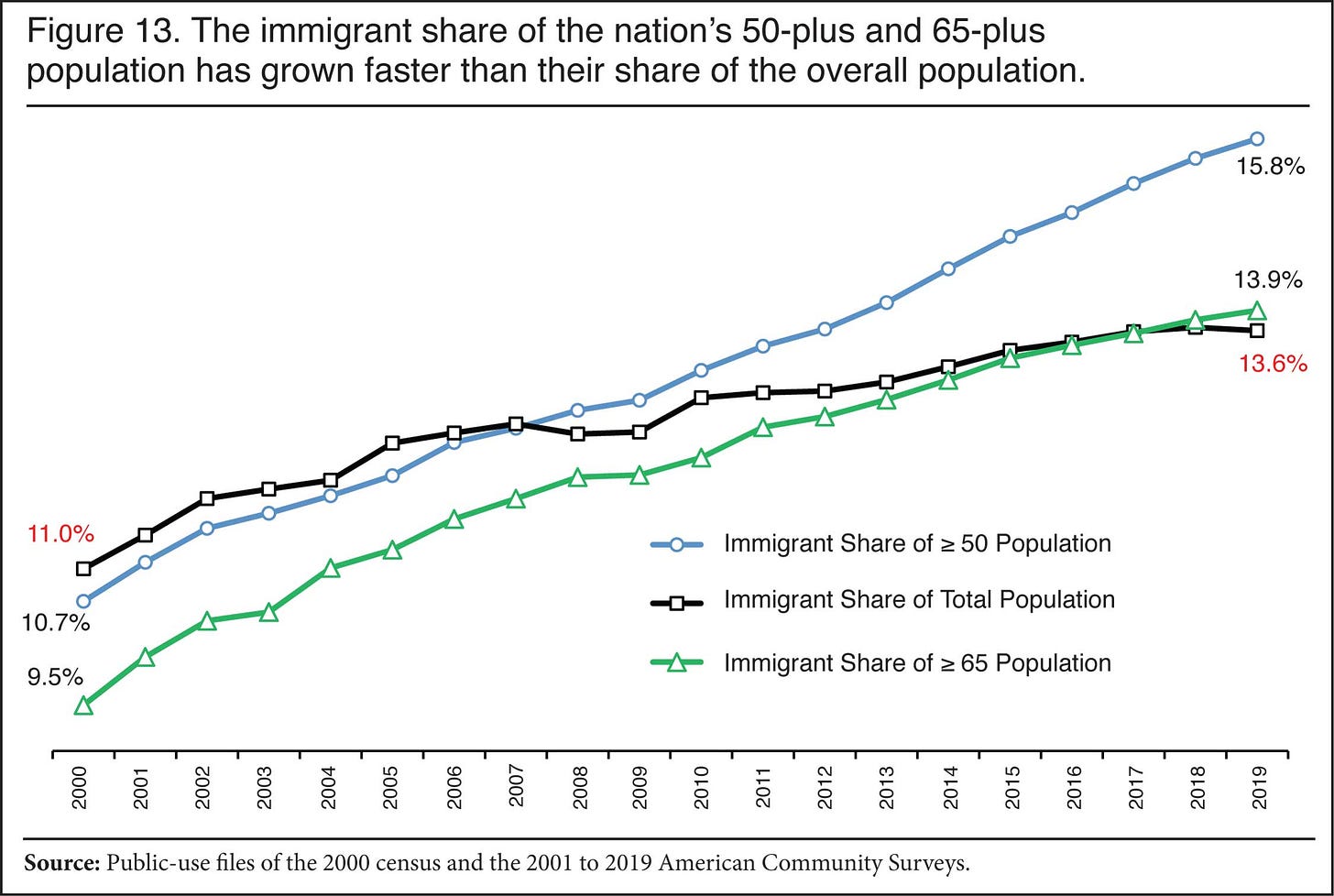

The immigrant share of the American population of those aged 50+ and 60+ has increased over time as well:

What this means is that if anything, we should expect that the immigrants who come to the United States in the future will be less productive than the ones who are here now. We have no reason to think that immigrants will become a net fiscal surplus in the future, and we certainly have no reason to think that they would become more beneficial to the economy than natives would, based on the current evidence that we have at hand of the projected trends for the future. As such, when it comes to the (lack of) economic benefits of immigration, this is not an argument that pro-immigration advocates can reliably use in their favor.

Social Trust

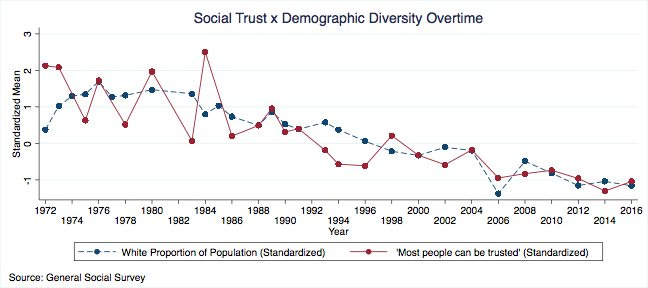

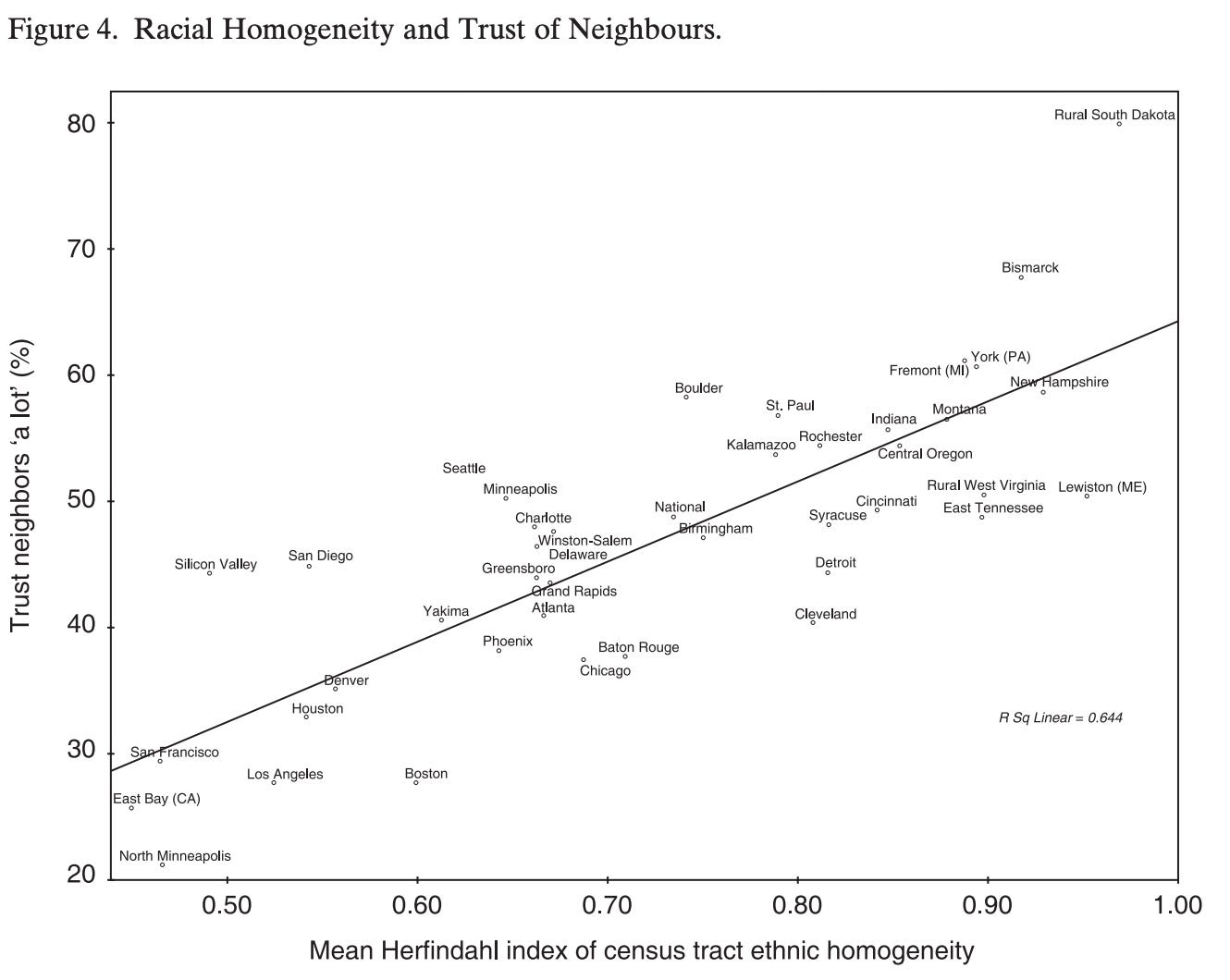

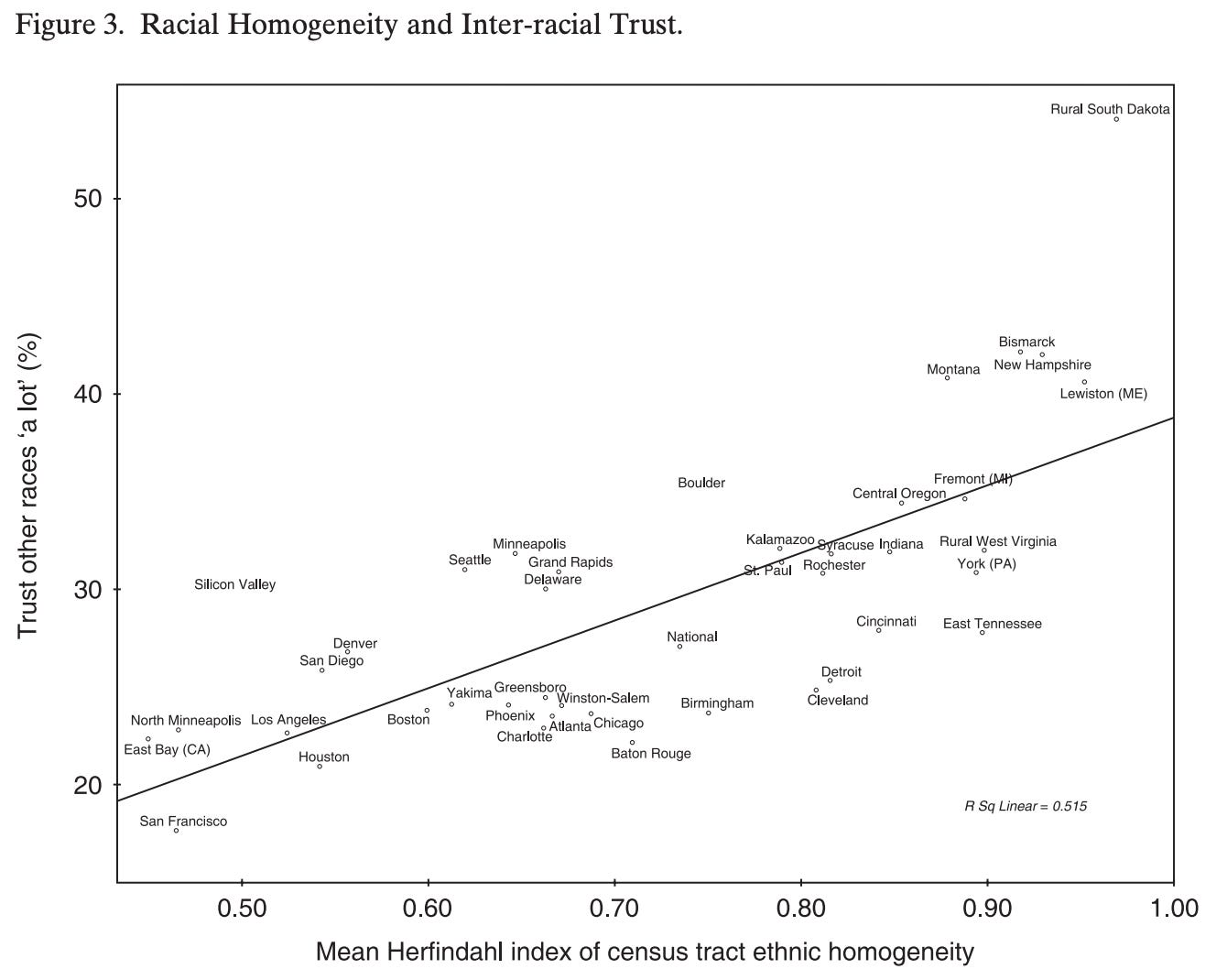

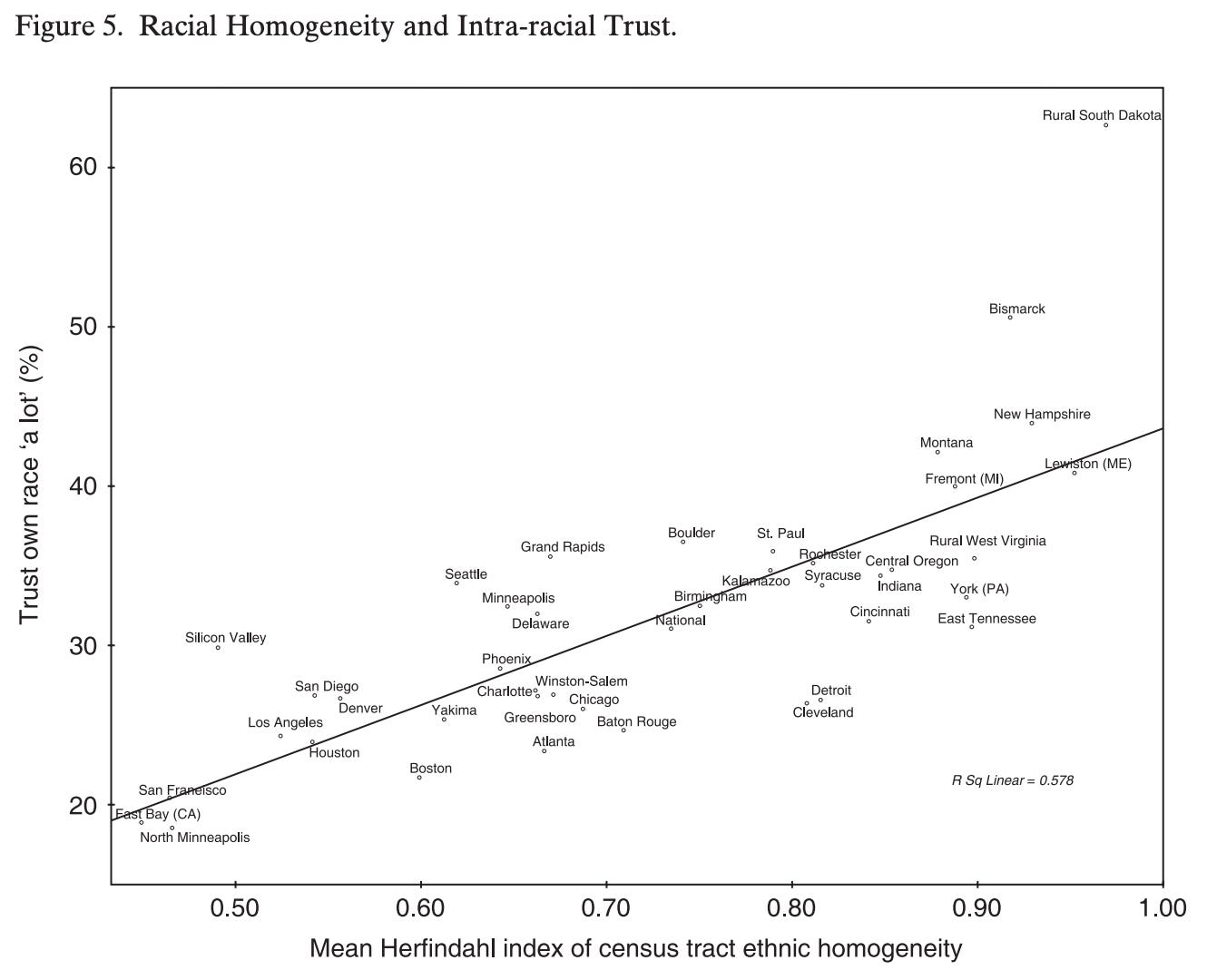

A less often mentioned but equally important factor to consider when discussing immigration is its impact on social trust in society. Higher social trust predicts greater happiness (Xu et al., 2023), economic growth (Bjørnskov, 2022), and even better quality of government (Stephen, 2000). Common sense tells us that people are more likely to be trusting and collaborative if they are surrounded by people similar to them, whether it’d be religious, ethnic, ideological, or otherwise. Because of this, we would expect diversity to harm social trust, which is exactly what we see. One of the most well-known pieces of evidence on this is from the book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American by Robert Putnam on the declining civic engagement in the United States. In it, he has found that even once socioeconomic status was controlled for, the greater the diversity in a community, the fewer people vote and the less they volunteer, the less confident they have in their local governments, local leaders, and local news media, the less they give to charity and work on community projects, the fewer close friends and confidants they had, the less happiness they felt, and the more time they spent watching television, because that’s really all you can do when you have no friends. In the most diverse communities, neighbors trust one another about half as much as they do in the most homogenous settings. Diversity, in other words, was more likely to make people go ‘bowling alone’, as the name of the book suggests. The results are once again vindicated by Goldberg (2018a), finding that the decline in trust over time and demographic changes are correlated at 0.66:

Putnam (2007) likewise found that again, controlling for socioeconomic status (need to keep emphasizing this since leftists will always try to bring this up as their go-to explanation for everything), diversity negatively predicts trust between neighbors, trust between races, and even trust within the same race. Among the native population, people fear the large presence of foreigners whom traitors can collaborate with against them and the fitness of the group.

Putnam’s results have also been replicated in the the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (Laurence & Bentley, 2015) and the negative impact of racial diversity also holds true across European regions (Lancee & Dronkers, 2008; Ziller, 2014). More recently, a meta-analysis by Dinesen et al. (2020) has put together 87 different studies on the topic of diversity and social trust has found that even after controlling for contextual socioeconomic deprivation (e.g., mean income or level of unemployment), individual socioeconomic status (e.g., education or income), contextual crime, and individual minority status (e.g., being of immigrant origin or member of a racial minority), diversity had a negative relationship with social trust.3 Now, the meta-analysis did find that the estimated relationship between ethnic diversity and social trust is somewhat weaker in models adjusting for interethnic contact, but the difference is far from statistically significant. The findings look like this:

The negative effects don’t stop there however, as diversity doesn’t just lower social trust, but also elevates conflict. Researcher Tatu Vanhanen in his book Ethnic Conflicts: Their Biological Roots in Ethnic Nepotism analyzed 176 countries and has found that diversity, or what he calls ‘ethnic heterogeneity’, explains around 66% of the variance in the estimated scale of ethnic conflict.

Vanhanen also tried to see if the level of socioeconomic development of a country would reduce ethnic conflict, and the answer is partially yes, but the relationship was so weak that socioeconomic development, which he measured using the Human Development Index, only explained 16% of the variance in the estimated scale of ethnic conflict, which is to say that it’s unlikely for improved living standards to be able to offset the increased amounts of ethnic tensions brought on by diversity.

Democratization was found to be an even weaker variable, explaining only around 5% of the variance.

Despite all this overwhelming evidence, however, some still attempt to challenge this idea. There is a popular theory known as ‘contact theory’ which proposes that higher diversity will, over time, result in more interactions between ethnicities and will thus reduce biases and distrust between them. This sounds very nice and all but it doesn’t hold true in reality. Last (2022) looked at this and pointed out that once you correct for publication bias, then the supposed mediating effect of contact on racial diversity and trust disappears.

Limited English Proficiency

Still yet, the problems with immigration do not end there. In 2013, around half of the entire U.S. immigrant population of 41.3 million that year had only limited proficiency in English. The increase in the limited English proficient population from 1990-2013 was driven basically entire by immigrants (Migration Policy Institute, 2015):

Let’s compare California and New Hampshire for example. California has 10.5 million immigrants in 2021 making up 27% of its total population (Perez et al., accessed 2023), whereas New Hampshire has only 80,000 immigrants making up 6% of its population (American Immigration Council, 2020). The literacy rate of California is 76.9% compared to 94.2% for New Hampshire (World Population Review, accessed 2023). Part of this trend can be explained by the fact that immigrants tend to live in ethnic-majority communities, which reduces their need to learn English to participate in society (Beckhusen et al., 2012). Worse yet, increases in immigrant student populations necessitate ESL classes, cause overcrowding at schools which diminishes the resources available on a per-capita basis, and create uncomfortable situations where native-born students are isolated by majority-foreign language-speaking immigrant students. This is American taxpayer money that could’ve gone to improve the educational performance of native-born students, but is instead being used to accommodate immigrants who will arrive in larger numbers if harsher restrictions on immigration are not imposed. From a paper titled “The Impact of Immigrant Children on America’s Public Schools”:

The California State Department of Education estimates that 16 new classrooms will need to be built every day, seven days a week, for the next 5 years. That’s effectively one new school per day! The number of teachers will need to be doubled within ten years, meaning that 300,000 new educators will be required.”22 That’s just in California!

This is the scale it would take to accommodate immigrant children in our school system sufficiently, and it’s completely infeasible. Likewise, it’s not just students who require more taxpayer dollars - adult immigrants with English deficiencies will most likely need English education at local community colleges, which local governments must earmark funds for. These aren’t the only burdens on public services that not speaking English provides - American taxpayers must also fund translation services at places like hospitals for immigrants to receive service. Some have proposed bilingual education as a solution to this, but that’s a terrible idea. Firstly, it is extremely expensive. The same paper noted that it costs nearly twice as much per-capita to education a child in a foreign language than it does to educate a native-born child in English. About a fifth of students in Californian school systems are being educated in foreign languages (Mitchell, 2017). Huh, that’s funny, California, you say? What was their literacy rate again? Oh wait-

So it seems to be quite a drain on government resources, and it doesn’t seem to work too well either, as a 1998 article from the Atlantic noted:

The final report of the Hispanic Dropout Project (issued in February) states,

While the dropout rate for other school-aged populations has declined, more or less steadily, over the last 25 years, the overall Hispanic dropout rate started higher and has remained between 30 and 35 percent during that same time period ... 2.5 times the rate for blacks and 3.5 times the rate for white non-Hispanics.

About one out of every five Latino children never enters a U.S. school, which inflates the Latino dropout rate. According to a 1995 report on the dropout situation from the National Center on Education Statistics, speaking Spanish at home does not correlate strongly with dropping out of high school; what does correlate is having failed to acquire English-language ability. The NCES report states,

For those youths that spoke Spanish at home, English speaking ability was related to their success in school.... The status dropout rate for young Hispanics reported to speak English 'well' or 'very well' was ... 19.2 percent, a rate similar to the 17.5 percent status dropout rate observed for enrolled Hispanic youths that spoke only English at home.

Note: The Atlantic’s link to the Hispanic Dropout Project’s report doesn’t work, you can access it by clicking here.

So the issue isn’t even speaking a different language at home, it’s literally how well you can speak English. Numbers aside, there is a much simpler argument against bilingual education, which is that it should not be a country’s obligation to kiss up to foreigners. Why should we have bilingual education? It should be the responsibility of immigrants to integrate into our society, not the other way around. If we’re going to accept them into the country at all, they could at the very least speak in the tongue of the natives. Imagine thinking it's wonderful to live in a community where nobody has anything in common, not even language. Imagine trying to sell this idea to the Turks or the Japanese that they should cater to foreigners and teach bilingualism for their sake. They’d laugh at us. Only those of us in the West are deeply confused and stupid enough to be able to justify something so stupid. These are the same people (white liberals) who will tell you that diversity is a wonderful thing and then run away from it for themselves (Kaufmann, 2023a, 2023b), hypocrisy at its finest.

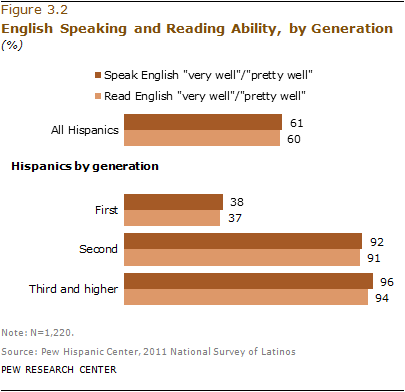

One last thing that I want to mention here is that the problem is likely to be understated even given what I’ve already said so far. This is because measuring English proficiency among immigrants, especially Hispanic ones, is more complicated than one might initially think. When measured using self-assessment, you often see a more optimistic picture like this:

The problem with self-assessment is that it’s not a particularly accurate method of gauging proficiency, and in the case of Hispanics especially, they have a tendency to substantially overstate how proficient they are in English. This is demonstrated by the fact that when proficiency is measured by actually administering tests, they perform much worse than their self-assessed levels would suggest (Richwine, 2017).

If immigrants were truly learning English so well and there was nothing to be worried about, it must truly be strange that every time I use an automated phone call service, there’s always an option for Spanish. Something fishy is going on here. Of course, the answer is quite simple if you don’t assume that Hispanics are being completely honest about their proficiency, and neither are pro-immigration advocates.

Assimilation

Language is not the only issue of course, as increased immigration is also going to pose difficulties to the process of assimilation. Advani & Reich (2015) found that if the minority group is small in its population size, then it will indeed assimilate and absorb the dominant culture, but if their population reaches a critical mass, then rather than assimilate, they will instead self-segregate and maintain their own distinct culture. This is congruous with the fact that the most racially diverse cities in the United States are often the most segregated (Silver, 2015). Well, given the racial demographic changes to the United States that has been occurring for several decades, we’re definitely at a point now where assimilation seems to not be happening anymore. For one, patriotism has been on the decline in the United States and this is true regardless of whether you measure it by simply asking respondents to choose their level of patriotism or by asking them to describe how they view Americans:

Despite this, white Americans remain the most patriotic racial group, and not just the most patriotic group, but one which is the most likely to feel extremely patriotic (Cannon, 2021; YouGov, 2022).

One might be curious as to whether or not these differences are merely a function of something other than race itself such as gender, age, and income. Trende (2021) looked into this and found that when these variables are controlled for, the difference in being patriotic with non-Hispanic whites as the reference group is -17% for Hispanics, -48% for blacks, and a whopping -89% for Asians.

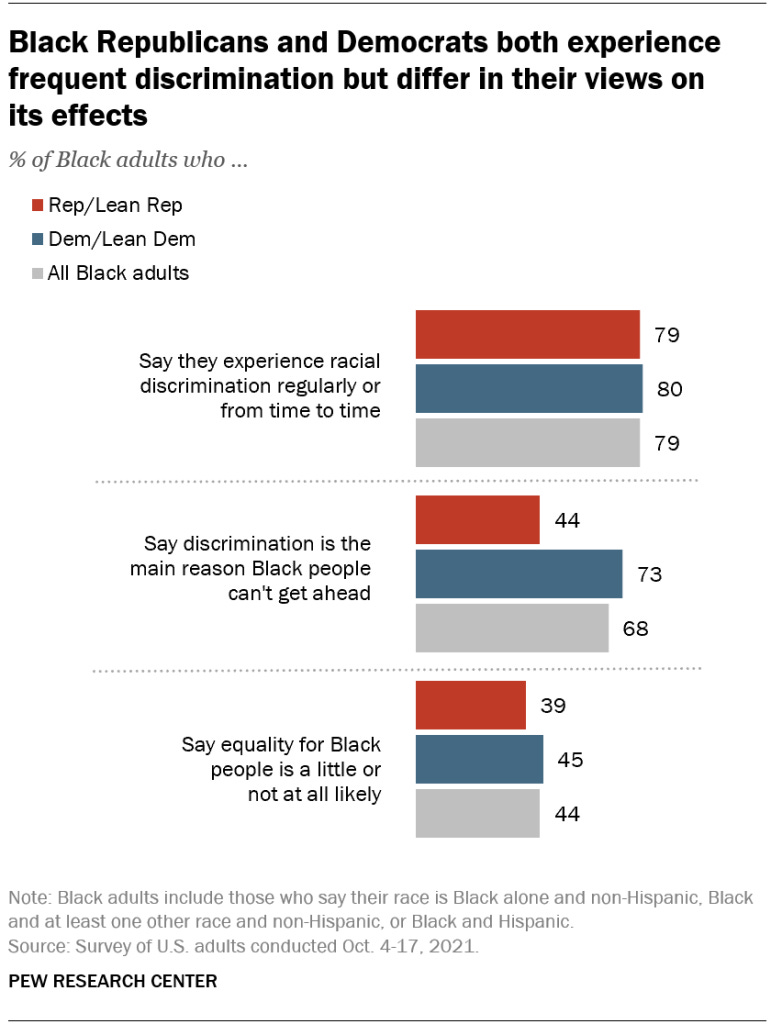

As the country’s demographic changes, we may also expect that the concept of assimilation itself becomes twisted. Republicans generally have an idealistic notion of minorities adopting small government, traditional family values, Christianity, etc. but those are not the dominant values of the country anymore, leftism is, and immigrants only exacerbate the acceleration of leftism through their support for it. Take Asian Americans for example, who were once net Republicans but this is no longer so. However, even minorities who are Republicans do not necessarily share the same beliefs as white Republicans do. This is evidenced by the fact that black Republicans are quite likely to believe that discrimination against them exists and is a major obstacle (Cox et al., 2022) than white Republicans do (Horowitz et al., 2019) or that Hispanic Republicans favor gun control and amnesty more than non-Hispanic Republicans (Krogstad, 2022).

The point on Hispanics is particularly concerning because a large portion of political alignment is a function of selection (i.e., Hispanics with various characteristics and dispositions self-select into either party) and Hispanic Republicans being more supportive of amnesty in practice means that they support allowing more migrants over who will be more likely to have leftist leanings. This is a cost of immigration that many people ignore even though it is just as much of an issue. Even if you were to grant that immigrants are good for the economy, it ignores the very real long run cost of giving them citizenship and then their children voting for civilization extinctionism. I mentioned Asians earlier and since Asians have absorbed shitlibbery extremely effectively, you end up getting this:

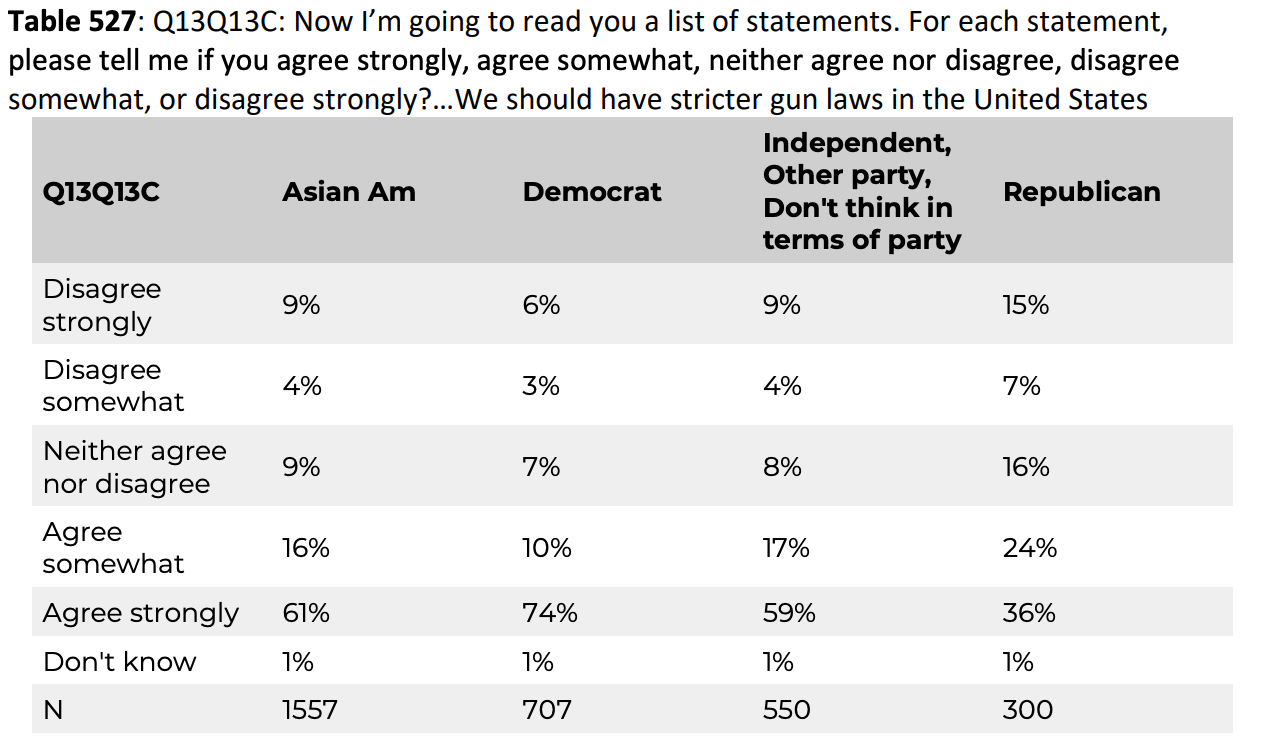

Oh yeah, remember how I said just because a minority is Republican doesn’t mean they believe the same things as white Republicans? This goes for Asians as well, here are those same results broken down by party identification:

So, we can see that for Asian Republicans, 35% support shifting spending from law enforcement to programs for minorities, 60% favor more gun control, 42% support a pathway to citizenship for illegal migrants, and 56% support affirmative action. Those percentages speak for themselves.

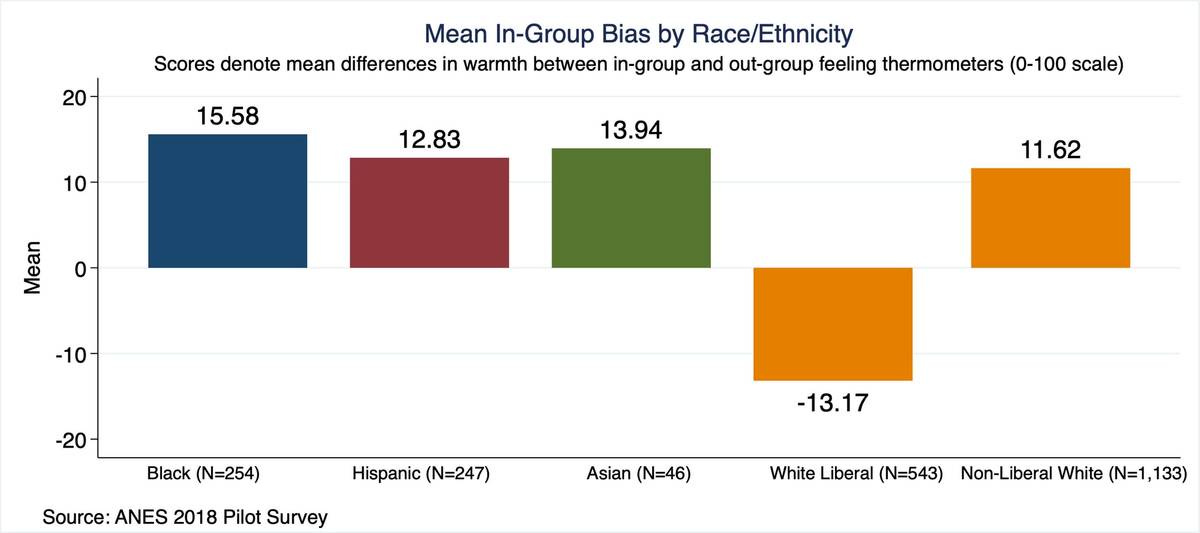

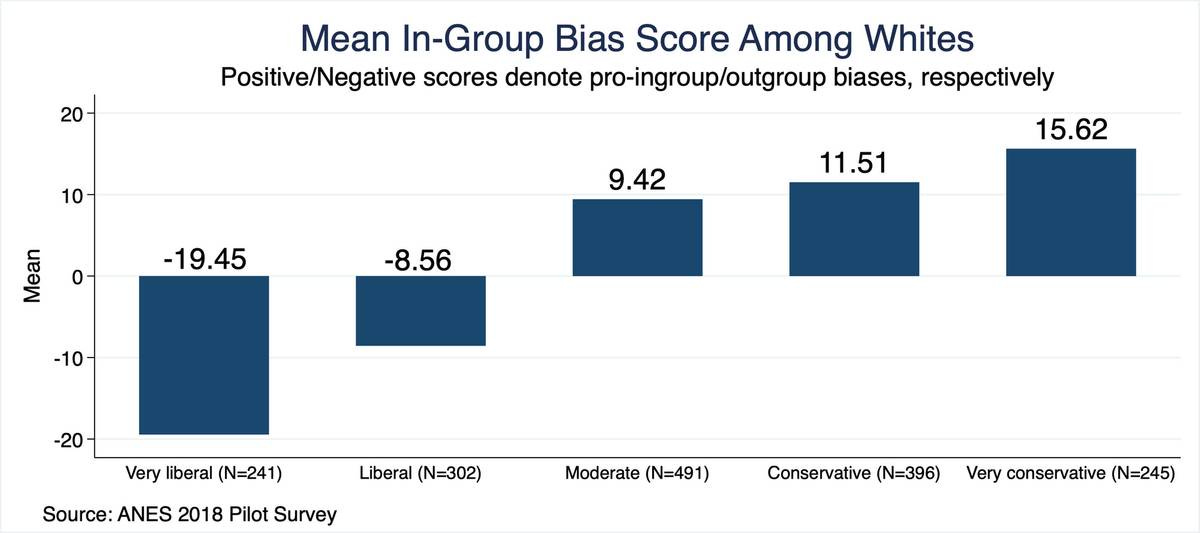

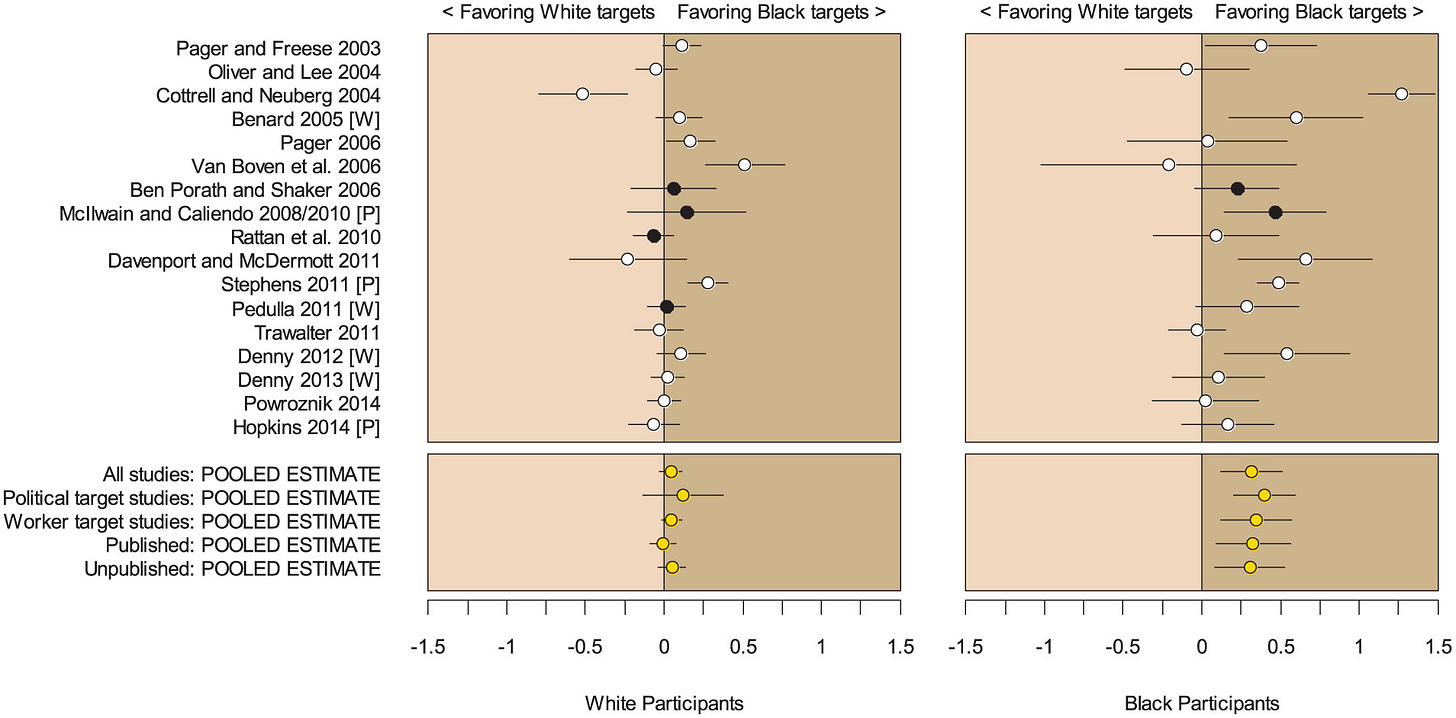

We also know that non-whites demonstrate stronger in-group bias than whites (Goldberg, 2018b):

Now, this is a bit unrelated, but I did want to point this out. Goldberg (2019) breaks down the ratings of whites by liberal and non-liberal, and this reveals something quite telling:

White liberals are the only group to have a negative in-group bias, which is to say that they hate their race, maybe this explains why they’re so keen on advocating for open borders, not from the kindness of their heart, but out of self-hatred. It’s worth keeping this in mind when you hear these people promote anti-nativist rhetoric. The fact that whites demonstrate the lowest in-group bias overall among the races is also consistent with survey results showing that nonwhites are far more likely to view their race as central to their identity than whites (Horowitz et al., 2019):

This is also congruous with the evidence showing that whites are the only racial group who are more likely to identify with their country than with their race. Non-whites identify with their race about as strongly as white conservatives, except for blacks, who identify much more strongly, and with the country about as strongly as white liberals (Data Depot, 2023).

Perhaps more concerning is the attitudes of races towards each other. Whites on average gave all races equal ratings, that is to say that they have the most egalitarian view of all races, whereas all other races gave themselves the highest ratings and whites the lowest ratings and the differences in ratings for the different races were higher among nonwhites than whites (Zigerell, 2021):

Now, one might see all of this and claim that these results cannot be trusted because white Americans might simply be lying on surveys, but the lack of bias among whites manifests even in experimental evidence whereby the perceived race of the subject that the white participants believe he or she is dealing with is manipulated. By contrast, black participants demonstrate moderate levels of pro-black bias (Zigerell, 2018).

I think it’s pretty clear now at this point to anyone reasonable that modern immigration is overwhelmingly a net negative. Americans have far too optimistic and benevolent views towards immigrants, and supporting it would be subjecting themselves and their nation to suicide. However, there will always be some who remain defiant against this obvious truth, and so I will address some of the commonly used bad arguments in favor of immigration.

Bad Arguments For Immigration

“Fixing” the Declining Birth Rate

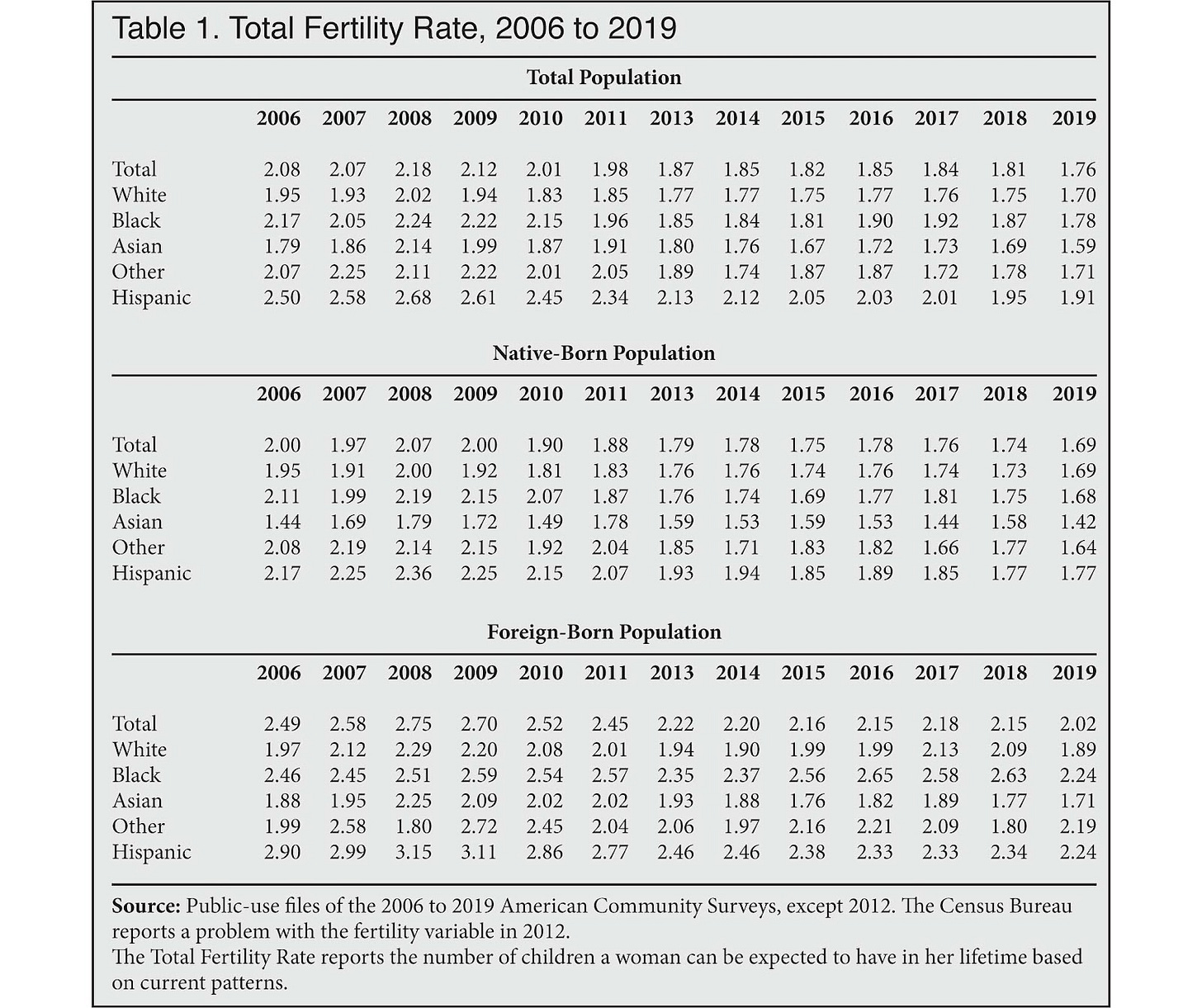

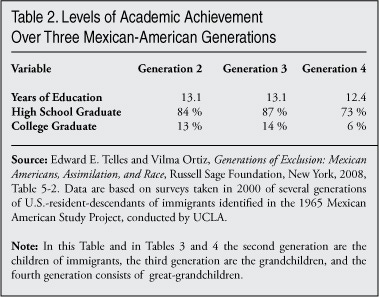

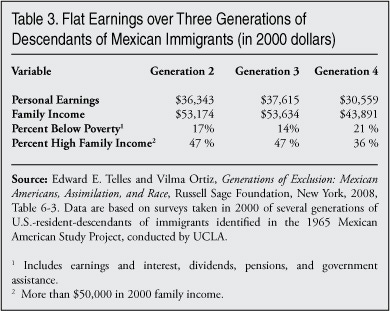

A commonly used argument in favor of greater immigration is that the native fertility rate is in decline, and so by bringing over immigrants, this would be able to compensate for this problem. However, ignoring all the other problems with immigration that I’ve mentioned, is this a reasonable claim to make? Well, let’s find out. First off, the fertility rate of immigrants is in decline as well. In 2008, Hispanics (the largest immigrant group) had already peaked in fertility before going on a sharp decline while Asian numbers continued to only get steeper with time. Moreover, the fertility rates of native-born blacks and Hispanics are at parity with native-born whites (Camarota & Zeigler, 2021b; Livingston, 2019):

Not only that but in 2019, the fertility rate of immigrants has also dropped below the replacement rate of 2.1 (Camarota & Zeigler, 2021b):

In fact, it’s Hispanic fertility, which has seen the sharpest rate of decline in the United States (Stone, 2019):

With regards to the children of migrants having reduced fertility compared to their parents, this is not unique to the United States. We also have data from Denmark which indicates that the fertility gap between first generation immigrants natives close after about one generation and second-generation immigrants have the same fertility rate as natives (Kirkegaard, 2018).

There’s also some evidence that immigration reduces native fertility, albeit this reduction is mostly short-term (Seah, 2018). But keep in mind that immigrants are constantly entering the country, there is no ‘pause’ on immigration, and so it would make perfect sense for this effect to continue and drag on. Moreover, since immigrants do displace native workers and lower their standards of living as established earlier (refer to the section “Wages and Worker Displacement”), this is going to disincentivize even more natives and make them have less children. The last thing to consider is that, as mentioned earlier, immigrants are entering the country at an older age, meaning that less of them are going to have children (old hags aren’t exactly fertile y’know), but on top of that, also consider the fact the gap between the average age of natives and new immigrants is closing (Camarota & Zeigler, 2021a).

What’s more, if we look at immigrants overall, then not only are they older than natives but they’re also aging more rapidly:

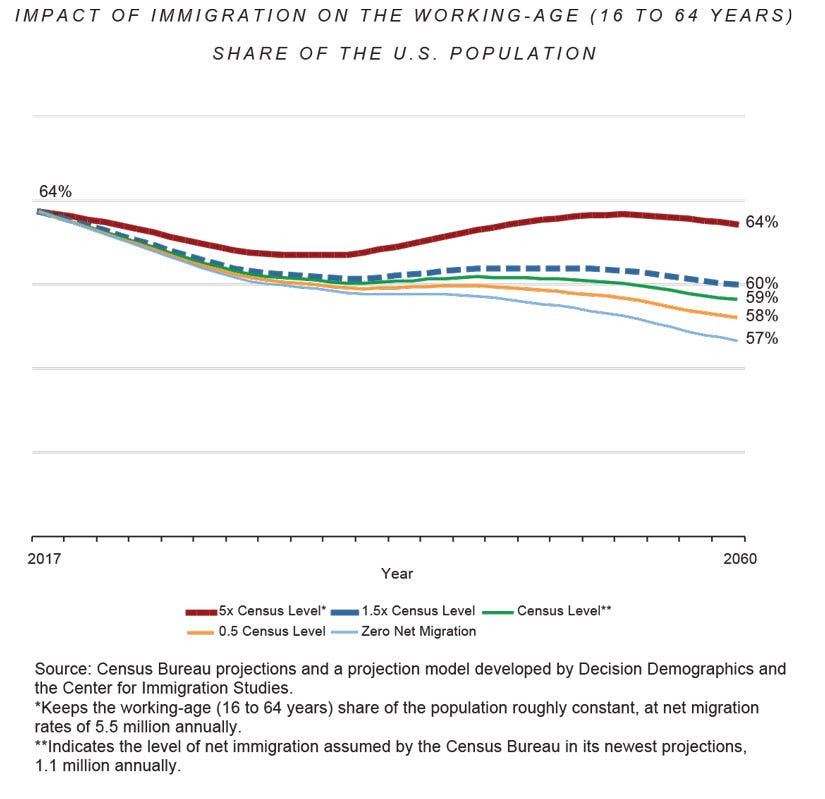

So, with all that said, what is the effect immigration has on population aging? It’s minimal. It would take quintupling the level of immigration that we have currently to maintain the working-age share of the population.

When you examine the grand scheme of the world, this is not surprising as the whole world is seeing symptoms of population decline. The hope of using Hispanics to substitute native fertility doesn’t seem like it will work in the long run either. With this being the circumstance, why should one wish to bring more outsiders into the nation, given the ongoing crisis we already have currently? Besides, even if migrant fertility can be used to stifle population decline, this fertility is not desirable because it will be coming from less productive groups that are closer to being net drains on society than net benefits. Assuming that having more people will automatically make things better ignores the unequal distribution of productivity in reality. Regardless, it doesn’t fix the ongoing problem we are facing going forward and will do more harm than good in the long run.

Paying for Social Security

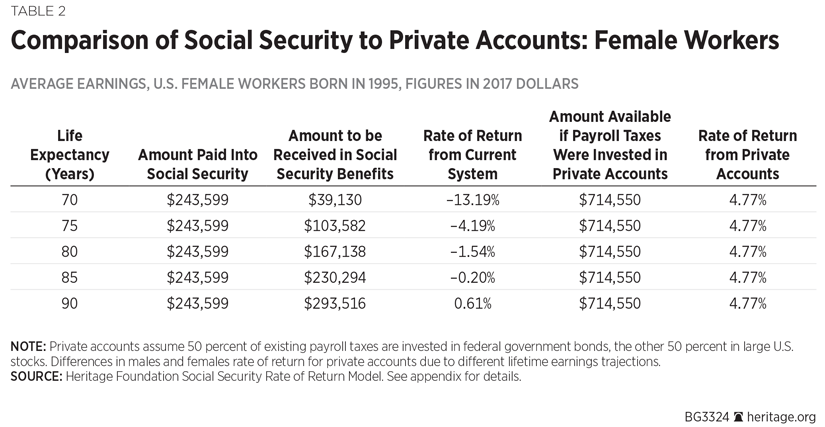

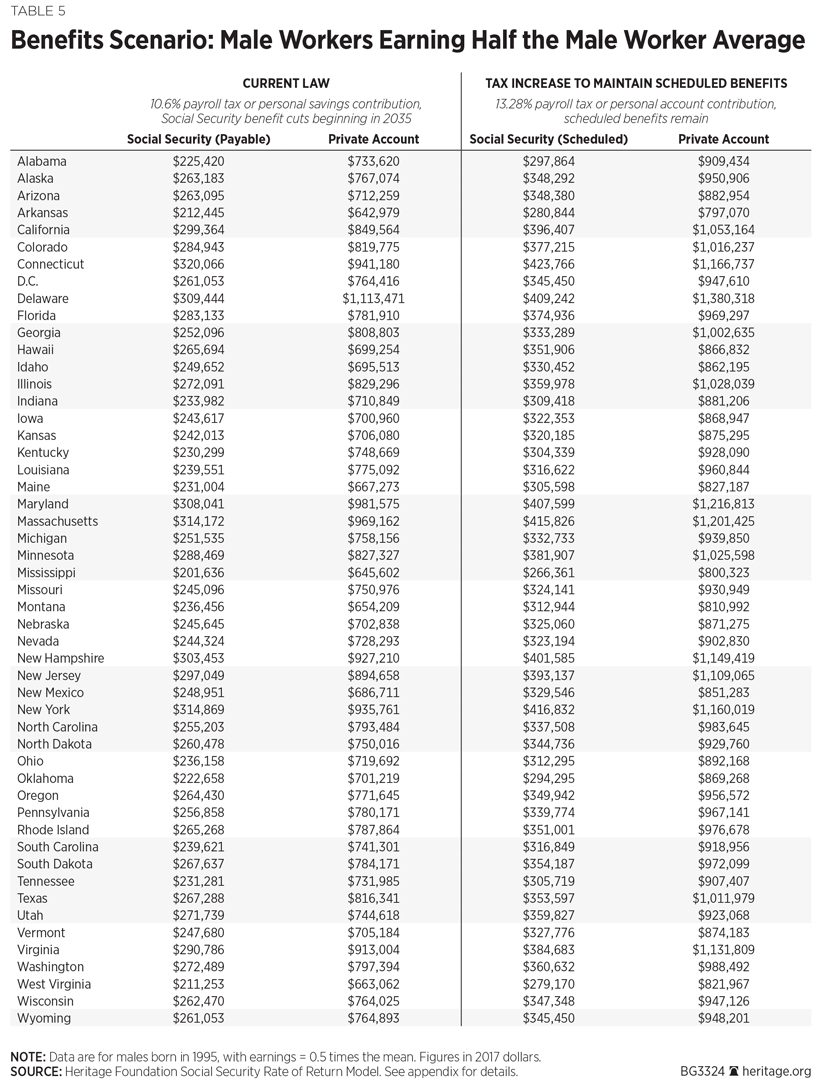

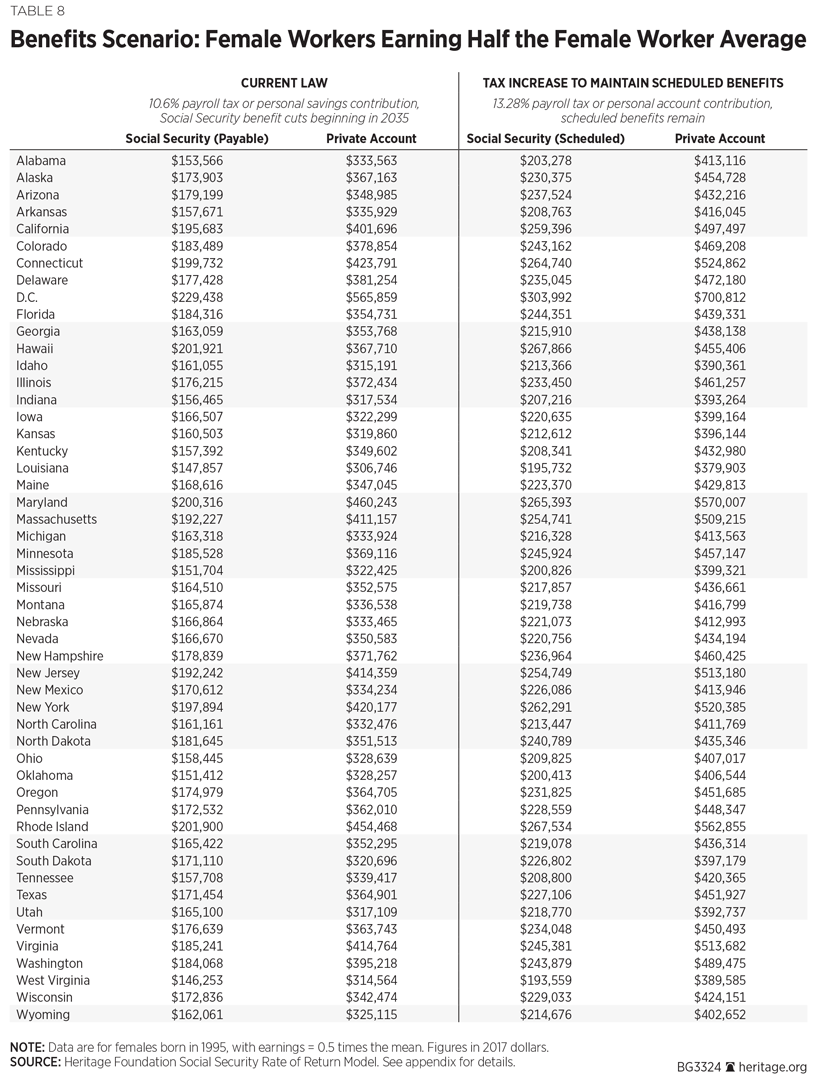

Speaking of the long run, another common argument used in favor of more open immigration is downstream from the fertility rate argument, that being that immigrants will help pay for the social security of the increasingly aging population. Well, first of all, the fertility argument is complete nonsense, and immigrants take out from the system more than they give (refer to the section “Welfare Use and Fiscal Impact”), so already this argument doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. However, the problem here really isn’t whether or not immigrants can help pay for social security, the problem is social security itself and the fact that it’s mostly a ponzi scheme. Benefits exceed contributions and it discourages recipients from continuing to work by reducing up to 50 cents for each dollar in earnings, and the latter part would explain why the retirement age has been dropping in the United States. A solution to this would be privatization, as that would not only better align benefits and contributions, discourage people from retiring too early, and they’re likely to receive more than they would under the current system (Rosenblum, 1997; Dayaratna et al., 2018).

A counter-argument to this is that privatizing social security might hurt low-income workers and exacerbate wealth inequality, but social security as it currently exists is already doing that by siphoning away what little wages they have into a ponzi scheme which is expected to become insolvent before they retire. In reality, even low-income workers are likely to benefit from privatization due to much higher return rates in the private market than U.S. treasuries.

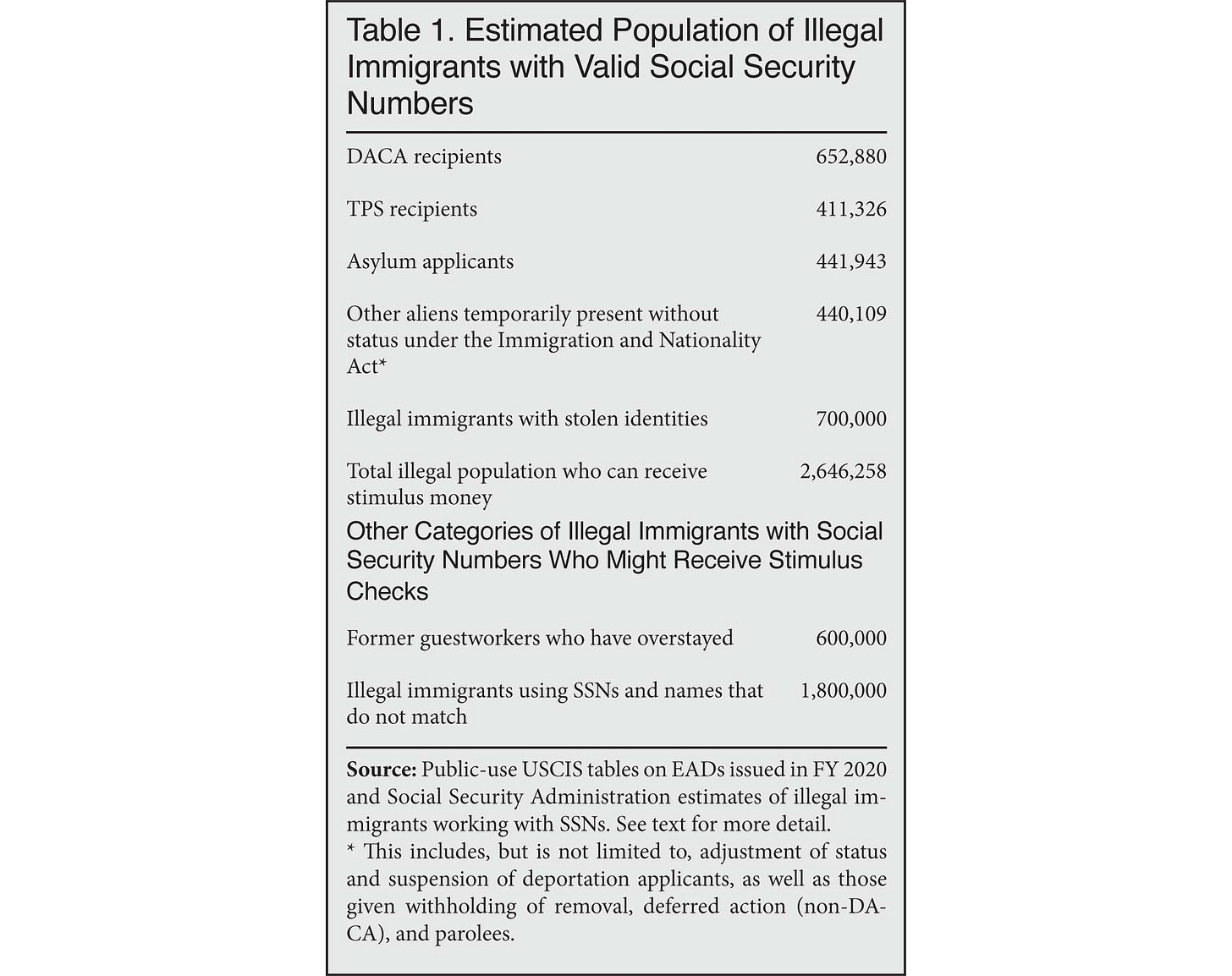

It’s also funny that the risk of hurting low-income workers is a concern when it comes to social security but not when it comes to importing more of the third world for shitlibs, but consistency is the last thing that should be expected of them. There are a billion proposals to fix social security, many are and demonstrate more intelligence than advocating for mass demographic change which is completely insane. This ridiculous argument partly relies on the assumption that illegal immigrants do not have access to social security, but even this is debatable. Camarota (2021b) looked at various government sources and estimated that nearly 2.65 million illegal immigrants have valid social security numbers, and this is divided into the following categories:

Secondly, regarding immigrants in general, THE NEW ARRIVALS WILL NEED THEIR SOCIAL SECURITIES PAID WHEN THEY RETIRE. This will require more immigrants, and so on, which is a destructive cycle. Using immigrants to solve the social security deficit is just a way of delaying the problem and not addressing it, as opposed to getting to the root of the fact which is that it functions as a ponzi scheme, and more immigrants to solve it will only make it worse as it will require even more immigrants. The problem will only be exacerbated. Fuck the boomers anyway, they ruined this country, so might as well let them suffer and die.

“Unwanted” Jobs

It’s commonly been argued before that immigrants are really only taking jobs that Americans don’t want. This is just blatantly untrue. Given the choice between having no work or having a blue collar job, everyone would pick a blue collar job. It's just that many of these jobs are providing lower wages due to competition from immigrants. Beck (1996, p. 102) provides a historical example of how the idea of ‘unwanted jobs’ is blatantly untrue:

In many cases, so-called immigrant occupations already have Americans working alongside foreigners. There are plenty of unemployed Americans who might take those jobs if they began opening up after a halt in immigration, especially if the workplace culture once again became American- and English-speaking. That was demonstrated in 1995 when immigration agents conducted massive arrests of illegal aliens, removing thousands from plants in six southern states. Within days, the majority of those vacant jobs were filled with American workers. “That says something about the oft-heard claim that illegal workers take only the jobs legal workers don't want,” said Doris Meissner, head of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Tens of millions of dollars in annual income was transferred overnight from aliens to Americans. If there were plenty of Americans to take the jobs illegal aliens had, one has to assume there would be even more willing to do the work that legal immigrants do.4

Oh so you mean that when immigrants leave, Americans will in fact take those jobs? Who could’ve guessed right? The book further explains:

For other “immigrant jobs,” there may not be a sufficient number of Americans who would take them as they now exist because the pay and working conditions are so deplorable-the meatpacking industry being a notable example. The presence of immigrants keeps those wages and conditions from improving to the point where Americans would take the jobs. Without the availability of new immigrants, though, employers would have to make innovations and improvements in their employment, and in doing so, most would find enough Americans to keep their business running. “You hear the myth so much that immigrant farmworkers take jobs Americans won't do, that Americans won't clean the streets, clean the rooms, wash the dishes,” says economist Marshall Barry of the Labor Research Center of Boston and Miami. “But that isn't true. If you pay right, Americans will do everything.”

So yes, immigrants are the reason why Americans don’t want these jobs. Employers will gladly choose to hire cheaper labor since it lets them keep more of their profits, and it makes the conditions of these jobs awful. It makes sense when you think about it rationally. Outside of the states that are swarming with migrants, who do you think is doing all the ‘unwanted jobs’? You think states that have barely any immigrants are yearning for floods of them so that someone will finally occupy all those jobs that supposedly no native will take? Or maybe, the more realistic scenario is that in states that don’t have many migrants, the natives are the ones doing those jobs. Gallup (2015) had conducted a survey across 142 countries on the topic of whether or not immigrants take wanted or unwanted jobs, and the results are as shown:

Notice that the lower the income the countries of those surveyed were, the more likely they were to believe that immigrants mostly take jobs that citizens in this country want, and in fact, from the ‘upper middle’ category all the way to ‘low’, a greater percentage of people think that immigrants mostly take jobs that citizens in this country want rather than thinking that immigrants mostly take jobs that citizens in this country do not want. Hmm, now why could this possibly be the case? Oh I dunno, maybe it’s because those with lower incomes are the ones who are suffering the most from competition with immigrants for jobs? Just a speculation, but they’re probably more likely to have had firsthand experience with immigrants hurting their prospects than the fat wealthy fucker living in his mansion. Now in truth, we don’t actually have to do any guessing, as Camarota et al. (2018) looked at the percentage native population within occupations, and here’s the list of the important findings:

Of the 474 civilian occupations, only six are majority immigrant (legal and illegal). These six occupations account for 1 percent of the total U.S. workforce. Moreover, native-born Americans still comprise 46 percent of workers in these occupations.

There are no occupations in the United States in which a majority of workers are illegal immigrants.

Illegal immigrants work mostly in construction, cleaning, maintenance, food service, garment manufacturing, and agricultural occupations. However, the majority of workers even in these areas are either native-born or legal immigrants.

Only 4 percent of illegal immigrants and 2 percent of all immigrants do farm work. Immigrants (legal and illegal) do make up a large share of agricultural workers — accounting for half or more of some types of farm laborers — but all agricultural workers together constitute less than 1 percent of the American work force.

Many occupations often thought to be worked overwhelmingly by immigrants (legal and illegal) are in fact majority native-born:

Maids and housekeepers: 51 percent native-born

Taxi drivers and chauffeurs: 54 percent native-born

Butchers and meat processors: 64 percent native-born

Grounds maintenance workers: 66 percent native-born

Construction laborers: 65 percent native-born

Janitors: 73 percent native-born