We Really Don’t Need More Foreign Students

If anything, we need much less, so while we’re at it, let’s start sending them back.

Consider the following proposal: I will roll a regular six-sided die numbered one through six. The die is entirely normal and has not been rigged. If the die lands on any number except for six, I will give you a dollar. However, if it lands on six, then I will blow your brains out with a desert eagle. Would you take the proposal? Some of you who feel a bit daring might. Okay, how about if we did this for five rounds? Ten? A hundred? After a certain point, you probably wouldn’t because the bad outcome is that much worse than the rewards of the good outcome, regardless of the fact that you’re always more likely to not roll a six than to actually do so.

Now, consider a modified version of this proposal in the form of a brand new admissions policy: every time we accept an international student, we spin a chamber. Five of the chambers are empty, and if any of those click, we get a little reward. Maybe we get a decent coder, maybe a brilliant grad student. But if the sixth chamber clicks? BOOM! There goes a trade secret, a fighter jet blueprint, or, if you want to appeal to historical accuracy, the Twin Towers.

This is the problem that the advocates of immigration don’t understand despite it being fairly intuitive. The benefits of foreign students are generally modest, and even though most foreign students are not intentional saboteurs, the cost for when things do go wrong is extremely high.

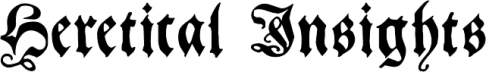

It is not immediately obvious that foreign students are some top-tier talent that we desperately need, given that immigrants are less skilled than their native counterparts at the same education level, both among immigrants who were educated outside of the United States and immigrants who were educated in the United States, though obviously the gap is smaller among the latter than the former (Recueil, 2025, Richwine, 2019; 2022).1

The number of foreign students has exploded in recent times, with the latest available data from the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System putting it at over 1.5 million, and over a third of those have work authorization (Feere, 2024). Where were all those benefits we were supposed to get? Of course, it’s true that immigration and economic growth are correlated, but granger causality tests find that it is economic growth which predicts increased immigration and not vice versa (Morley, 2006). Moreover, foreign students are coming from places where corruption and cheating are common, and, unsurprisingly, the students bring that problem over when they come here. It might not come as a surprise to learn that Asians in the United States commit a lot of academic fraud as well, despite current perceptions of them as being ‘model minorities’.

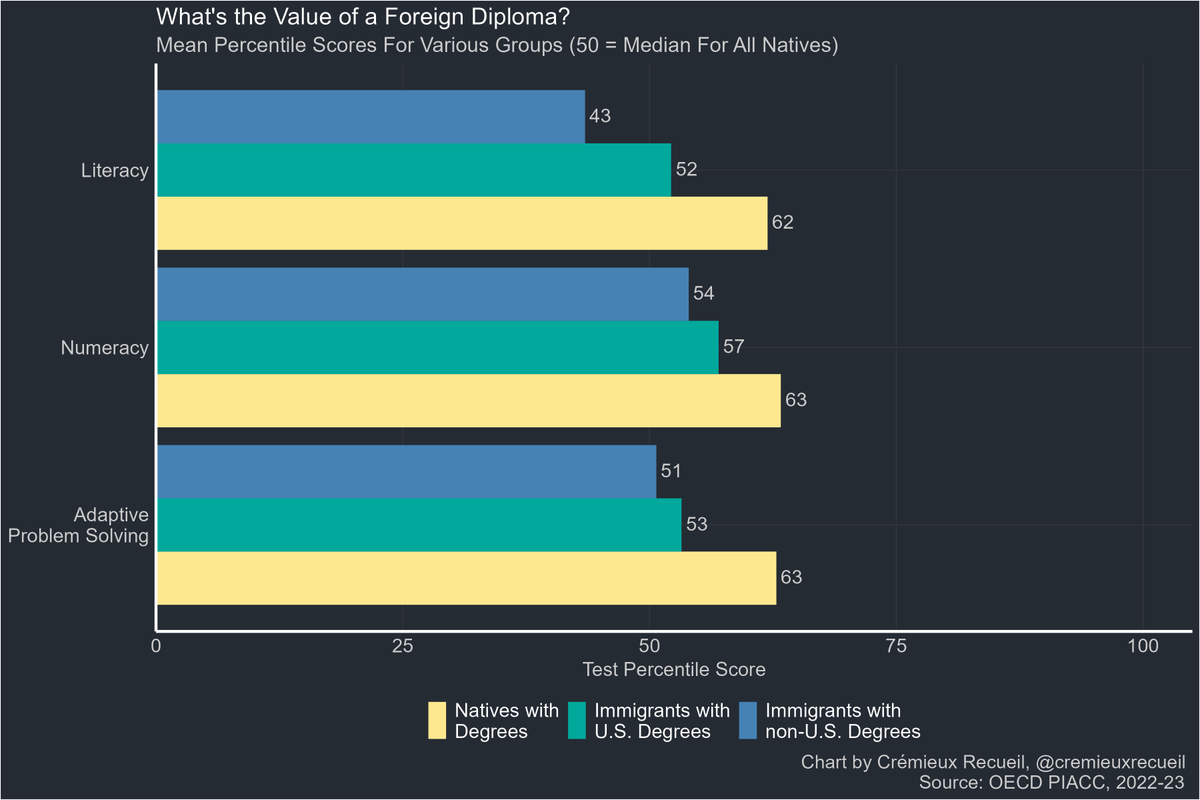

Where are we getting foreign students from in recent times? Well, mostly India and China, similar to the H-1B situation (Buchhloz, 2025).2

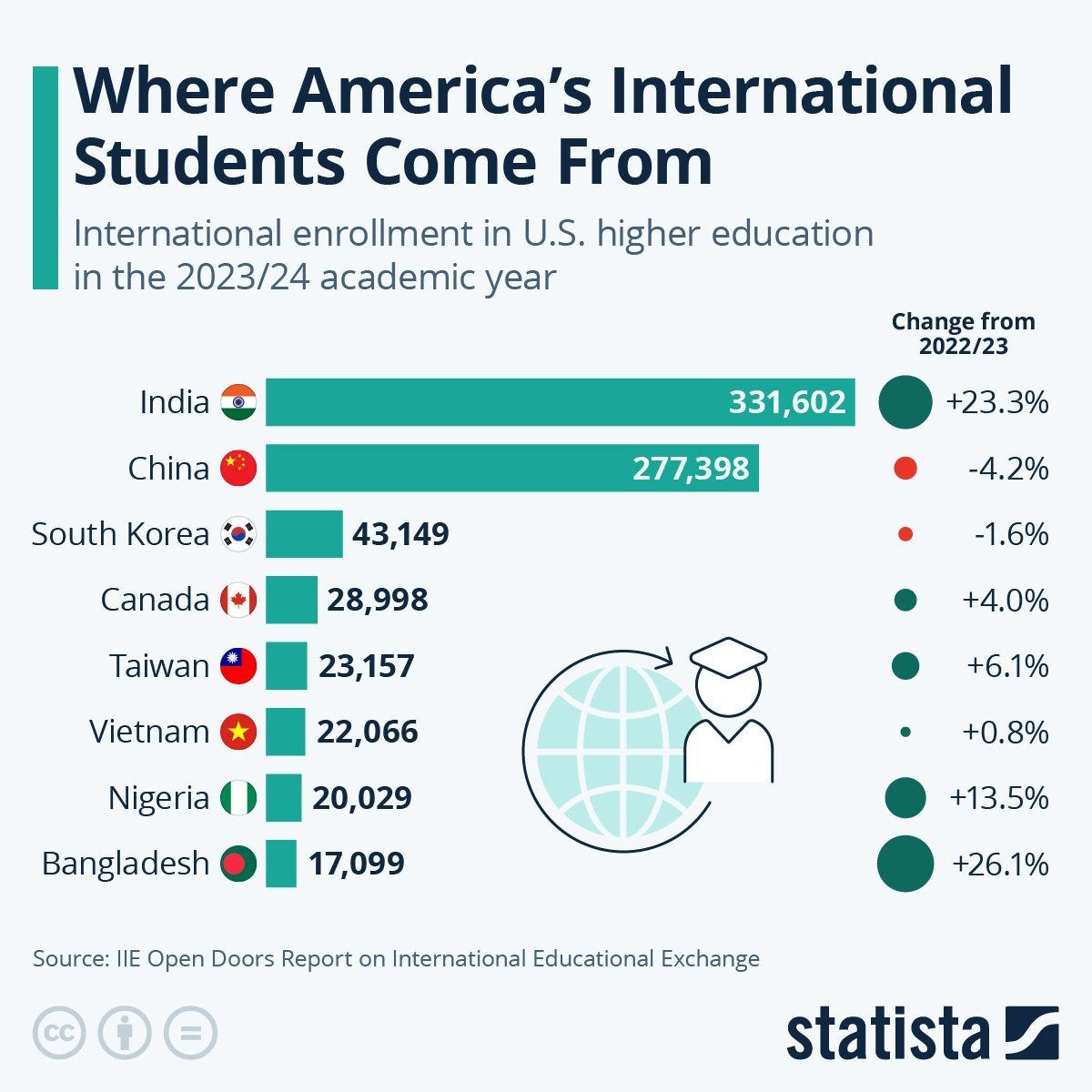

India and China are both underrepresented among measures of innovation relative to their share of H-1B beneficiaries or immigrant STEM workers (see my analysis on this here), so it is not obvious that importing foreign students is helping us get the “cream of the crop” from the world, or if it is, the global “cream of the crop” is really not that impressive. Moreover, since Indian immigrants in particular are 1) a highly selected sample, and 2) extremely hostile to the very aspects of American culture which made it successful in the first place, they would actually incur a net loss for the country in the long run if more are admitted.

As for Chinese students, I didn’t think it was necessary to say this, but clearly, it needs to be said: no, Chinese students coming from China are not going to help the United States “beat China”. This idea at its most charitable is excessive naïve optimism and at its worst is just bordering on delusional because, unlike us, the Chinese still have a strong and healthy sense of ethnic identity and have almost no loyalty to our already barely existent conception of being an ‘American’.3 Amusingly enough, the American government seemingly recognized this over a decade ago, with the U.S. Pentagon even publishing a long report in 2013 on the racist attitudes of Chinese people and viewing it as a major strategic advantage that China holds over the United States (for some reason, it didn’t cross their minds that maybe we should adopt this strength from them), but now we’re all supposed to pretend that all the aliens who come here are eager to become an ‘American’. Well, to be fair, there is another option. You can also opt for anti-white liberal Chinese Americans instead, which would do a fine job of killing this country in the long run as well.

The other issue with this “beat China” narrative lies in our modern globalized system, because the reality is that the oft-touted claim of “immigrants improve innovation” goes both ways. To the extent that immigrants might marginally increase American innovation (though even this I have serious doubts), this benefit is offset by the fact that it benefits our opponents more than it benefits us. Rather than beating China by brain draining it, importing more Chinese students just helps to narrow the technological gap between the United States and China, as our technology gets diffused globally, allowing them to catch up to us. In one study which looked at the role of immigrants in American innovation (immigrants from where, they refuse to specify of course, but I have my gut feelings. Again, see my analysis on this here), the authors mention in the abstract that “Immigrant inventors are more likely to rely on foreign technologies, to collaborate with foreign inventors, and to be cited in foreign markets, thus contributing to the importation and diffusion of ideas across borders” (Bernstein et al., 2022). In section 4.4 of the paper which is dedicated to talking about the role immigrant innovators play in facilitating global technological diffusion, they note that (emphasis is mine) “in surveys of Silicon Valley, 82% of Chinese and Indian immigrant scientists and engineers report exchanging technical information with their respective nations (Saxenian (2002); Saxenian et al. (2002))” (p. 17). There is a well-documented history of Chinese spies in the United States stealing important secrets on behalf of the Chinese government. Each time a hostile country successfully catches up to us in some area thanks to using foreign students as espionage, that would have to be compensated for massively, such as with another technological boom in another sector, but there’s no evidence that the latter actually happens thanks to foreign students.

This leads me to the final obvious point that needs to be made, which is that new technology has breakthrough potential into other areas, and, in a country with sufficiently high national intelligence like the United States, said breakthrough is, more often than not, an inevitability. Just because someone who happens to be foreign-born wound up being the one to utilize the technology to develop another new thing does not mean this new thing never would have been developed without him. To quote @AnechoicMedia_ on this:

Most specific companies and their founders don’t matter that much to people not invested in them specifically. The economic activity they preside over was inevitable and it’s only a zero-sum question of who captures the market. The model of being a top business today has been to capture some conduit of economic activity, rather than being a manufacturer of widgets.

This is most true in the case of social media companies, which exist to maximize engagement and sell ads. The rise of a new media platform just re-routes a limited pool of attention to a new fiefdom. If any one founder of the site-that-would-be-twitter didn’t exist, it’s not like the economic activity represented by twitter ceases to exist from that timeline. But the people in charge do matter to the rules that are in place and what content gets promoted, so handing control of your media to foreigners loses native editorial control while creating no new value.

The same is true of much of the tech world that exists as extensions of physical services. Something like Uber was inevitable as soon as the smartphone proliferated. Ride-sharing systems with electronic reputation management was imagined by writers as early as the 1970s. The smartphone made this politically unstoppable, and it was only a question of which company would scramble fastest to grab the market, by the most legally questionable means.

If you add a hundred new genius “founders” to America, there’s not going to be a hundred Ubers or Twitters because the market was only ever going to support a particular concentration of firms, a certain amount of user engagement, a certain amount of consumer spending to collect fees on. As an American it’s more important that the set of institutions enabled by present technology end up being controlled by people who share your values.

So the question is not whether we should let in more foreign students because they might build the next Google or code a few more apps. The question is whether we are willing to keep spinning the chamber again and again because we’ve convinced ourselves that the statistical odds are in our favor when it in fact isn’t. At some point, you have to ask what exactly we think we’re gambling for. The truth is, civilizations don’t die when they’re defeated, they die when they forget who they are. You can only mortgage a nation’s future so many times before you have nothing left to leverage but delusions.

Note also that this skills deficit is largely not due to language bias (i.e., English).

This figure here is also underestimating the true numbers. The source is the IIE Open Doors Report on International Educational Exchange, which, as explained by Feere (2024), is a voluntary survey that doesn’t include all schools and all student visa types.

If the political gaps between whites and nonwhites isn’t already sufficient evidence, being “color-blind” is also unique to white Americans on net. This is also why the identity of being ‘American’ is shared by whites more than other races, whereas nonwhites identify more strongly with their race instead.

Great article.Will you ever do an article on the jQ question

The point about closing tech gaps is real, but... to be fair, Paul Collier studied this extensively and foreign students also tend to export liberal/americanised political attitudes back to their home countries as well (at least when and if they move back.)

Great article otherwise, in total agreement.