False Rape Accusation Research is Terrible

Don't believe all women, especially not the ones who wrote these papers

In 2009, the National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC) published a literature review titled “False Reports: Moving Beyond the Issue to Successfully Investigate and Prosecute Non-Stranger Sexual Assault.” This report pulled together estimates from “methodologically rigorous research”,1 and claimed that all these studies find false rape accusations to make up only 2-8% of total rape accusations.

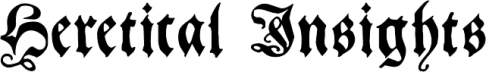

The first study cited is the Making a Difference Project (MAD), which, the authors claim, found 140 false reports in a total sample of 2,059. And, indeed, the final report for MAD does give a figure of 7.1%, slightly different because “unspecified cases” were not included in the latter. However, it does not make much sense to use this figure, when a further 8.5% of accusations were deemed to be unfounded/baseless, and the vast majority of the rest of the cases were closed prematurely. Here’s the percentage breakdowns of the cases:

Let us assume that all cases in which there is an arrest or the report is exceptionally cleared (i.e., the assailant is probably known, but cannot be arrested because of reasons outside the case) are true accusations. This means that, at the very least, 37.9% were not false accusations. Of course, baseless accusations cannot be ruled as being definitely true, but it would also be unfair to label them as false accusations. Therefore, they should simply be excluded from the sample. Cases closed as information reports should also be excluded, as these are those for which the investigators could not reach a conclusion. Suspended and inactivated investigations should, likewise, be excluded, as no verdict could be reached in those. Therefore, only 45% of the cases can actually be analyzed to find out the prevalence of false accusations. 7.1/45 is roughly 15.78%, this being the proportion of false accusations in cases where the investigators could come to a conclusion.

The next citation is to a book by Lorenne Clark and Debra Lewis, which examined 116 cases investigated by a Canadian police department in 1970. Of these cases, 42 were classified as founded by the police, all of which judgements were agreed with by Clark and Lewis. A further 74 cases were, by the police, taken to be unfounded, though Clark and Lewis disagreed with many of these decisions. Clark and Lewis’ analysis of the cases concluded that 42 were founded while 12 were unfounded, and the rest “possibly founded.” Of the unfounded reports, 7 were made by the victim herself, leading to a figure of 6%, which was used by the NSVRC. However, this does not make much sense. First, a case being unfounded does not necessarily make it false. And, most importantly, if accusations made by someone else on the woman’s behalf should not be counted in the number of false accusations, why should they be counted in the total number of accusations? In conclusion, all that this study can tell its readers is that about one half of all accusations deemed to be unfounded are not brought by the alleged victim.

A study by Grace et al. of 302 British rape cases reported in a three month period in 1985 was the next citation. According to Grace and colleagues, there were 67 instances in which police did not charge the accused. Of these, 29 (43%) were caused by the victim withdrawing her accusation, and another 23 were false (34%). In the rest of these 67 cases, there was either insufficient evidence to attempt prosecution, or the woman refused to testify on trial or cooperate with law enforcement, and, in two, the complaints were nullified because the woman was accusing her husband. The first two types of cases will be categorized as false, while the rest of these will be excluded from the analysis entirely. The remaining sample is made up of 287 cases, of which 52 are false, for a total false accusation rate of 18.12%. According to the NSVRC report, 8.3% were deemed false. This number appears to come from the number of cases deemed false (23) divided by the total number of cases, but with the withdrawn accusations taken out of the denominator. The last step is not done for any other calculation, so this seems to be a decision that was made early on and was only accidentally kept in the final publication.

The next estimate came from a paper by Jessica Harris and Sharon Grace, based on several hundred English rape cases from 1985 to 1996. In 25% of cases, police “no-crimed” the accusation, and in another 31% of cases no further action was taken. Because Harris and Grace provide the distributions for reasons given for not taking further action or for “no-criming,” it is possible to estimate what percentage of cases to include as false accusations. In 36% of cases in which police no-crimed, the reasoning was that the victim withdrew the accusation, and in another 43% of cases they did so because the accusation appeared to be false. In the rest of the no-crime cases, the victim refused to testify or there was insufficient evidence, as well as a few miscellaneous reasons. Therefore, 79% of no-crime cases should be taken as false accusations, while the rest of the no-crime cases should be excluded from the sample entirely. For cases in which no further action was taken, these two categories represented about 55% of all accusations, though the category of seemingly false accusations is close to zero. As before, 45% of these cases will be excluded from the sample, and the remaining 55% will be counted as false accusations.

The remaining categories were cautioned (i.e., police thought that the accused was guilty, but did not prosecute; 1%), undetected (i.e., the assailant was never found; 11%), and charged (31%). Of course, when the assailant was never found, it is difficult to know if the charge was true. To be conservative, I will include all of these as being totally made up of true accusations, and therefore they will all be included in the total sample. The total percentage included is 79.8%, and the percentage false is 36.8%, leading to a false accusation rate of 46.12%. The NSVRC report included all cases in the denominator and only considered no-crime cases which were deemed by police to be false as being untrue, and therefore greatly underestimated the prevalence of false reports at 10.9%.

Next cited is a report by Liz Kelley and colleagues, which examined a few thousand British cases. The most comparable data are the figures for police, which are based on 2,284 attrition cases (meaning that the cases did not reach a final verdict). Of these, 1,817 could be categorized: in 386 cases, there was insufficient evidence (21.24%), in 318, the accusation was withdrawn (17.50%), in 315, the victim did not go through with the original process (17.34%), in 239 the offender was undetected (13.15%), in 216 the allegation was deemed false (11.89%), in 83 cases there was no evidence of force (4.57%), and in 260 other cases there was some miscellaneous reason (14.31%). Cases with insufficient evidence of the event or of force should definitely be removed from the total sample, and the accusations deemed to be false as well as those in which the accused withdrew should be counted as false accusations. As before, we will be conservative in including cases where, e.g., the accused was never found, in the total sample. This method gives total sample of 1,348, of which 534 (39.61%) were false. Because the attrition rate was 68.75%, this means that the actual false allegation rate was 27.23% (because cases that get to court are assumed to be truthful accusations).

It should be noted that Kelley et al. also reanalyzed the police’s perceptions of false accusations, and concluded that a better estimate is 67 false accusations, or 2.53% of the total sample (including all cases, not just the attrition sample). If this number is used instead, the false accusation rate changes from 27.23% to 19.64%. The NSVRC report cites the former and latter figures as being 8% and 2.5%, which are the figures obtained if no part of the sample is excluded and only those deemed as false reports are counted as false.

Last referenced was Heenan & Murray’s study of 812 Australian rape cases between 2000 and 2003. In 15% of reports, police charged the accused, 46.4% resulted in no further action, 15.1% concluded with the withdrawal of the accuser, and in 2.1% of cases, the accuser was directly said to be making a false accusation. The remaining cases were still ongoing. As before, those who withdrew their accusation will be counted as false accusers, as well as those who were categorized as such. Cases resulting in no further action were said to be caused by the investigators’ confidence that the report was false in 30% of instances, and these cases should be included in the portion of false accusations, while the rest should be removed from the sample. Because investigations still ongoing are, obviously, less likely to have been those in which the police doubted the victim’s testimony, these will be included in the total sample under the assumption that all of them were true accusations. This methodology generates a false accusation rate of 46.16%.

To conclude this section, we will point out that a woman withdrawing her rape accusation is not necessarily a factual admission that the accusation is false, though this is the most obvious interpretation, and, if it were not true, it would imply extremely high false confession rates (see below). However, even if cases in which the accusation was withdrawn are removed from the sample, rather than being enumerated as false accusations, the rates would still be higher than those reported in the NSVRC report, as shown in the table below, which includes a summary of our analysis thus far:

It can be seen that, when analyzed properly, these studies suggest a substantially higher prevalence of false rape accusations than would be admitted by the NSVRC. The most basic error committed by the report—as well as, in some instances, those who wrote the cited studies—was to not exclude cases in which there was little indication toward either truth or falsehood from the sample. Another issue was failing to include cases of withdrawal as false reports—literally, these should be taken as an admission by the accuser that the original accusation was false, or at the very least, excluded from the denominator to not imply that they were true. Note, however, that we do not put much weight on even our own estimates from these studies, as the categorizations are almost always subjective. Also note that public #MeToo-style accusations may be more or less likely to be fraudulent than accusations made to police, so, even if these estimates could be taken at face value, their applicability to public examples would be tenuous.

There’s another side to this debate which warrants more discussion than what has so far been given. Because so many rape cases are ambiguous, a perfectly reasonable question to ask is what the rate of definitely true accusations is. If one calculates this number from the MAD study, using the same methodology as the NSRVC report used for false accusations, the rate can be estimated to be between 1.18-7.82%.2 Obviously, this number is far too low, and should not be trusted any more than the false accusation rates estimated in the same way. The purpose of calculating such a figure is to illustrate how easy it is to generate small numbers by bloating the denominator and diminishing the numerator (in this case, by only counting cases with a successful conviction as true accusations).

Besides the NSRVC report, the most commonly cited publication on this topic is Lisak et al. (2010)’s contribution to the Symposium on False Allegations of Rape, which concluded that, of 136 cases, 5.9% of allegations were false, and argued that “the prevalence of false allegations is between 2% and 10%”. This conclusion is highly misleading. Although the authors did look at a total of 136 cases, only 56 made it to prosecution, and it was only in these cases that Lisak et al. attempted to certify the veracity of the allegation. If you divide the total number of definitively proven false cases by the cases that made it to prosecution, then the false accusation rate increases to 14.29%. But there is yet another thing to consider: we can’t assume that ambiguous cases have the same likelihood of false reporting as the cases that actually made it to prosecution. Here is their description of their coding procedure:

False report: Applying IACP guidelines, a case was classified as a false report if there was evidence that a thorough investigation was pursued and that the investigation had yielded evidence that the reported sexual assault had in fact not occurred. A thorough investigation would involve, potentially, multiple interviews of the alleged perpetrator, the victim, and other witnesses, and where applicable, the collection of other forensic evidence (e.g., medical records, security camera records). For example, if key elements of a victim’s account of an assault were internally inconsistent and directly contradicted by multiple witnesses and if the victim then altered those key elements of his or her account, investigators might conclude that the report was false. That conclusion would have been based not on a single interview, or on intuitions about the credibility of the victim, but on a “preponderance” of evidence gathered over the course of a thorough investigation.

Case did not proceed: This classification was applied if the report of a sexual assault did not result in a referral for prosecution or disciplinary action because of insufficient evidence or because the victim withdrew from the process or was unable to identify the perpetrator or because the victim mislabeled the incident (e.g., gave a truthful account of the incident, but the incident did not meet the legal elements of the crime of sexual assault).

Case proceeded: This classification was applied if, after an investigation, the report resulted in a referral for prosecution or disciplinary action or some other administrative action by the university (e.g., the victim elected not to pursue university sanctions, but the alleged perpetrator was barred from a particular building).

Insufficient information to assign a category: This classification was applied if a report lacked basic information (e.g., neither the victim nor the perpetrator was identified, and there was insufficient information to assign a category).

An accusation was only enumerated as false if it was thoroughly investigated and proved to have been false beyond any reasonable doubt. Cases in which the victim withdrew her accusation, or in which there was too little proof to launch a serious investigation, were categorized as not having proceeded. Therefore, the cases which could not be included in the analysis (but were still included in the denominator by Lisak et al.!) were those in which the allegation was the most likely to be false. Of course, this would cause the false allegation rate to be considerably underestimated, even if the authors hadn’t erred by neglecting to prune the denominator.

Lisak et al. defended their overly strict rating threshold for false accusations by stating that, between the two teams responsible for coding each case, there was a very high rate of agreement—94.9%. Inter-rater reliability is a necessary but insufficient piece of evidence to prove that the results of this kind of analysis are to be trusted. High agreement doesn’t guarantee accuracy if a flawed rubric—like one prioritizing victim credibility unless disproven—could produce consistent but inaccurate coding across coders. For example, if all coders share an ideological lean (e.g., toward minimizing false accusations), they’ll consistently rate cases in the same way. Based on the information about the authors provided at the end of the paper, it is clear that they are advocates, whose work deals mostly with the alleged oppression of women.

While these are the papers often cited by advocates in support of the #MeToo movement, a study conducted by Kanin, published in 1994, is often cited in opposition. Kanin looked at 109 sexual assault reports from a Midwestern police department over a period of nine years, and found a false accusation rate of 41%. There are some reasonable criticisms that can be made of this study, such as the fact that its sample came exclusively from one police department. But the charges made against Kanin’s analysis by victim advocates are far from reasonable. The NSVRC report, for example, citing an earlier criticism of Kanin from John Lisak, accused Kanin of having relied on the discretion of the police officers themselves in determining whether or not a case was false. But this charge is not true. A case was only classified by Kanin as having been false if the original accuser admitted to it being false:

Additionally, for a declaration of false charge to be made, the complainant must admit that no rape had occurred. She is the sole agent who can say that the rape charge is false. The police department will not declare a rape charge as false when the complainant, for whatever reason, fails to pursue the charge or cooperate on the case, regardless how much doubt the police may have regarding the validity of the charge. In short, these cases are declared false only because the complainant admitted they are false.

Furthermore, police investigators’ judgement was the criterion used by most of the studies cited in the NSRVC report, relieving this objection from any weight it may have had if it were true. The second criticism by Lisak, as referenced in the report, was that Kanin did not provide a reliability analysis by comparing his evaluations to that of other researchers. In the case of Kanin’s study though, judgements were not subjective—the accuser either did or did not confess to having given a false report. Lastly, the NSRVC expressed concern about the fact that polygraph tests were used in the Kanin study. The popular perception nowadays that lie detectors are pseudoscientific is untrue; polygraph tests actually work just fine and are remarkably accurate. However, the accuracy of polygraphs themselves is not the criticism here. Rather, their main concern is that polygraphs may have caused victims to recant their initial accusation:

The reason is because many victims will recant when faced with apparent skepticism on the part of the investigator and the intimidating prospect of having to take a polygraph examination.

False confessions do exist, of course, but it is not clear how they would be gendered by a lie detector test. During the period of this study, lie detectors were regarded by the public as being close to inerrant, and, therefore, should have only led false accusers to take back their accusations. Indeed, this criticism bears no weight given a separate analysis from Kanin. In the addenda, he included data from police records regarding two large Midwestern state universities in 1988. Without any use of the polygraph, Kanin found a false accusation rate of 50%, though with a much smaller sample size (n=32). Even this addendum is easy to find, so it’s bizarre how they could have missed it. Kanin’s study isn’t flawless obviously, but it’s evident that the victim advocates trying to discredit him didn’t put much thought into the substance of their criticisms.

Furthermore, if the true false accusation rate is only 2-8%, the false confession rate in Kanin’s study would have to be astronomically high. Using a simple equation, the share of false confessions by the women in his sample would have had to been somewhere between 80.49 and 95.12%.3 This is ridiculously implausible.

This quick post is not meant to prove definitively what the false accusation rate is for rape or sexual assault reports; its much more humble goal is to establish that the oft-cited “2-8%” statistic is a product of activist number-fudging. In an earlier version of the NSVRC’s paper from 2007, the authors claimed that the true rate of false reports is 2-4%, the final version in 2009 revised it to 2-8%, and Lisak et al. claims it’s 2-10%. With how terrible the quality of the literature in this field of research is (its replication rate is probably lower than the true false accusation rate), the only thing one can say for sure is that the true false accusation rate lies somewhere between 0 and 100%. However, if one does choose to place his faith in the literature, the best estimate would be closer to 20-30%.

It was anything but methodologically rigorous, keep reading.

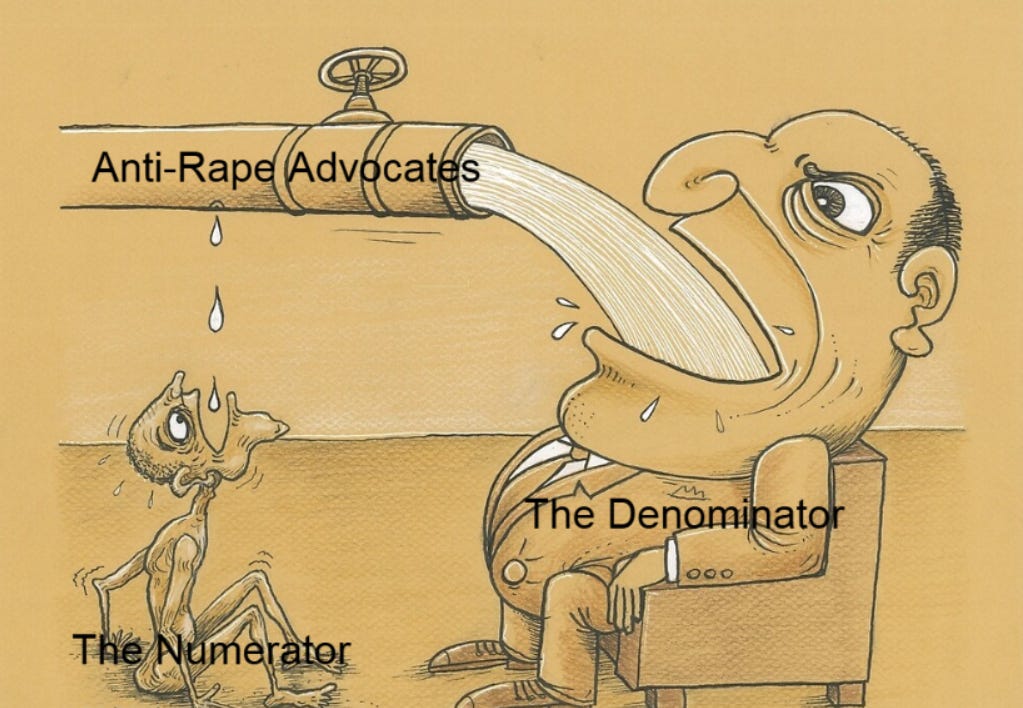

This is done by taking the 20% “cleared by arrest” value from the study as well as this figure showing how the prosecutions played out from the study:

According to this, 39.1% of all cases ended with either a guilty verdict or a plea of guilt. 20% × 39.1% = 7.82%. However, the authors of this study don’t consider a confession by the victim to be sufficient for classifying a case as false. So, if we only use the 5.9% of cases in which a guilty verdict was arrived at, then the “true accusation” rate becomes 1.18%.

Just to be clear, it is not at all believable that this estimate is accurately representing the reality of the situation, just as is the case with the official “false accusation” rate of 7.1%. Rather, it is merely a demonstration of the extent to which one is able to lie and manipulate the statistics for the purposes of pushing a narrative.

Suppose that the false accusation rate is 8%. Say you have 100 cases and 8 are genuinely false, but 41 are reported to be false. This means 33 of these cases that were reported to be false were driven by false confessions. 33/41 ≈ 80.49% for the false confession rate. What if we use 2% as the false accusation rate instead? Well, then the false confession rate would be 39/41 ≈ 95.12%.

You can ask women anecdotally if they've been raped, or sexually assaulted. Large numbers (10-30%) will say yes, which corresponds with research. Numbers get higher when you ask promiscuous women, prostitutes and so on. If you ask them, "did you report this to the police?" almost unanimously they say "no." When you ask why, they say, "idk." I hope that if I was raped that I would be dragging my prolapsed anus to the police station. But maybe there is some kind of deeper psychological mechanism at work which prevents them. I cannot speak to false rape accusations, having avoided that charge, and not knowing anyone else who has been falsely accused of rape. It does seem however that there are a ton of false charges being thrown around perpetually, especially in child custody cases.

Wait, you’re telling me the NIH hasn’t been dumping money onto anyone willing to investigate this?